The solution to the housing crisis seems simple—build more homes, make them affordable, house more people. Housing crisis solved.

But the problem with this “solution” is that it doesn’t consider zoning laws, specifically residential zoning, also known as RS-1.

Zoning and economic segregation

“Zoning is a tool that cities use to designate land uses. It came about trying to ensure people's safety,” explains Tiffany Muller-Mydrahl, a senior lecturer in the department of Gender, Sexuality and Women's Studies and the Urban Studies Program at SFU.

Zoning is a set of rules that decides which types of buildings can and cannot be built in certain areas of the city, including construction details like a structure’s height and width.

And while governments may say that zoning can help build community, resiliency and safety, it limits creating small, affordable housing on already expensive land.

Muller-Mydrahl emphasizes that zoning has always excluded people. In fact, critics argue that zoning promotes economic and racial segregation.

Since the rise of the middle-class, homeownership has been an important factor for wealth and privilege. Single-family homes are more expensive than apartments, which means racialized families who lack the economic privilege of white families are unable to live in one-family dwellings.

“Their origins are heteronormative, grounded in white supremacy and white privilege. They’re all about racial covenants,” she says.

While laws about which types of people can purchase, occupy buildings, or borrow loans are now illegal, zoning laws continue this legacy. Muller-Mydrahl says they function in the same ways.

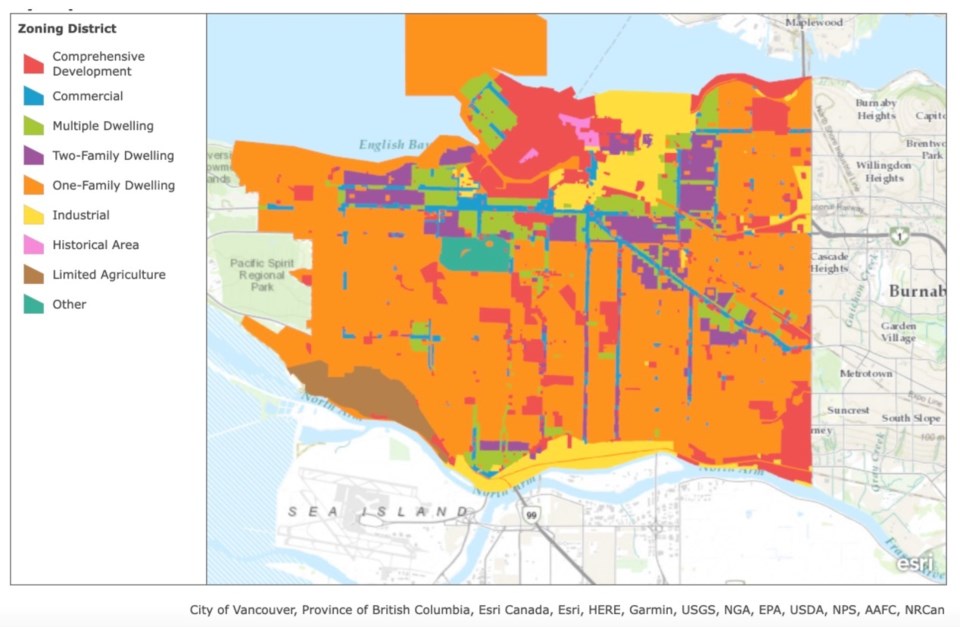

How Vancouver is zoned

There are three types of residential zoning: single-family dwelling, two-family dwelling, and multiple family dwelling.

Vancouver is zoned primarily for single-family dwelling, and most of the city is privately owned. Muller-Mydrahl notes that multiple family zoning is often on arterial roads, which means that these homes are “the buffer for air quality for single-family dwellings.”

For example, Knight Street is a multiple dwelling zone. But it is a known area where air quality is poor because of truck traffic pollution.

“What we are saying when we allow for multi-family housing in only one particular type of land, we are saying that we value single-family homeowners more than those who are able to afford housing in multi-family units,” says Muller-Mydrahl.

A need for rezoning

Zoning exists everywhere but some cities across the world are still able to create affordable housing. In North America however, there is little affordable housing to be protected.

When people think about solutions, they often turn to European cities where affordable housing is accessible. But this is because cities like Vienna, Austria never sold the land and so, housing is built on regulated land.

In order to create zoning for affordability, Muller-Mydrahl argues the city would have to buy back land from corporate land owners. More importantly, rezoning is what needs to happen.

“If somebody wants to build a multi-family unit within a residential or one residential family zone, they have to make all of these exceptions, and it just increases time and expense for the developer.”

But in addition to rezoning being costly and a long process, she says that people are afraid of this possibility.

“They're afraid of things like heritage designation and neighborhood character. So I would say, why do we have [zoning]? We have it because it's the way it has been, and people have a hard time imagining that they're not going to lose something if they agree to a kind of blanket rezoning.”