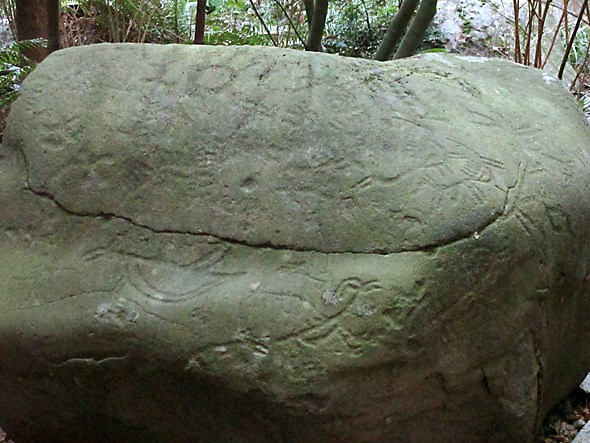

I don't know how many times I've looked at this rock through the window on the bottom floor of MOV and not realized that it's a petroglyph and that the writing on it is hundreds of years old. Read below to see what the deal is, then next time you're at MOV (maybe when you're checking out the SWEATERLODGE I told you about earlier this week) go and have a look for yourself.

There's a plaque inside the window (which is how I found out it's not just some mossy rock with scratches on it), here's what it reads:

"The term petroglyph is used to describe a rock which has been decorated with images carved into its surface. They are symbols that have been left by indigenous populations from the region, and are part of the legacy of the First Nations populations of the Pacific Northwest Coast. In the Pacific Northwest, petroglyphs are most often located along riverbanks and between tide lines along the coast. An example of a petroglyph can be seen here in the corner of this courtyard.

Upon first glance these designs may be thought to represent a form of language. Rather, petroglyphs should be viewed as a type of illustration as they cannot be "read" in the traditional sense. Designs portray creatures, both real and mythological, as well as humanoid figures. Much of the meaning of these carvings remains a mystery. Many western scholars have made attempts to interpret them. Some feel the carved stones represent myths once part of the oral tradition of this region. Some believe they functioned as property markers. Still others see them as being associated with ceremonies. It has been speculated that this petroglyph may have been a salmon marker. Another theory postulates that the rock was associated with puberty rites. There is little known oral tradition regarding these pieces. As well, because of their material and the fact that they do not erode at a uniform rate, contemporary archaeological techniques have not succesfully been able to date the stones. It is estimated that this petroglyph was created within the last five hundred years.

This petroglyph was carved in the vicinity of Lone Cabin Creek, north of Lillcoeta on the Fraser River. It first gained Euro-Canadian attention in 1923 upon its discovery by H.S. Brown, a Cariboo prospector. He brought its existence to the attention of William Shelly, the Vancouve. Parks Board commissioner of the era. Shelly proposed moving the six ton rock from its location on the Fraser to a new home in Stanley Par Three years later, the move commenced. The rock was first loaded onto a raft to be floated to the nearest railway station. This awkward plan failed as the incredible weigut of the boulder caused the raft to sink immediately after loading. The next, more succesful attempt involved a team of ten horses and a sled. In the dead of winter, the "Shelly stone" was dragged to the closest rail line. The whole procedure took over a month and cost Shelly two thousand dollars, an unbelievable sum for that time. The ''Shelly Stone" arrived safely at Stanley Park. It was set in a foundation of concrete as it was felt that this would prevent the enormous rock from being carried off or destroyed.

The rock remained at Brockton Point, mislabelled as an "Indian Pictograph", from 1926 until its transport to the Vancouver Museum in June 1992. During the years in Stanley Park, human contact and urban pollution have worn on the petroglyph like sandpaper. It is hoped that the protected environment of the museum will guard its images from further deterioration."