|

ReVIEWS, preVIEWS, interVIEWS, and overVIEWS: here's where you'll find out what the Vancouver Book Club team thinks about the literary scene in Vancouver. What you should read, where you should go, who you should sit up and notice. |

| Richard Wagamese talks about his new novel Indian Horse, the importance of writing from the heart, and the difficulty in being a blabbermouth and having to keep his National Aboriginal Achievement Award a secret. |

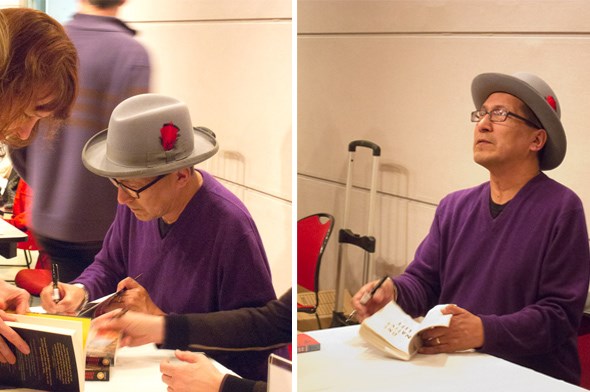

"Do you know your city has this persistent thrum, like a continual whup whup? And if you're not listening you can feel it on your skin?"

Richard Wagamese is addressing a group of about 70 book lovers at inCITE, a biweekly author reading put on by the Vancouver International Writers Festival. It's 8:30 at night and he's trying to explain why his energy is flagging, having been awoken by the city at 2:15 that morning.

It's an adjustment from what he has gotten used to since leaving Vancouver in 2007 and moving just outside of Kamloops, with his wife Debra Powell.

"A minute and a half beyond my door there is no one around me," he told me earlier in the day when we met to talk. "My dog and I just wander, walk around, and there's a connection with that energy that's in everything."

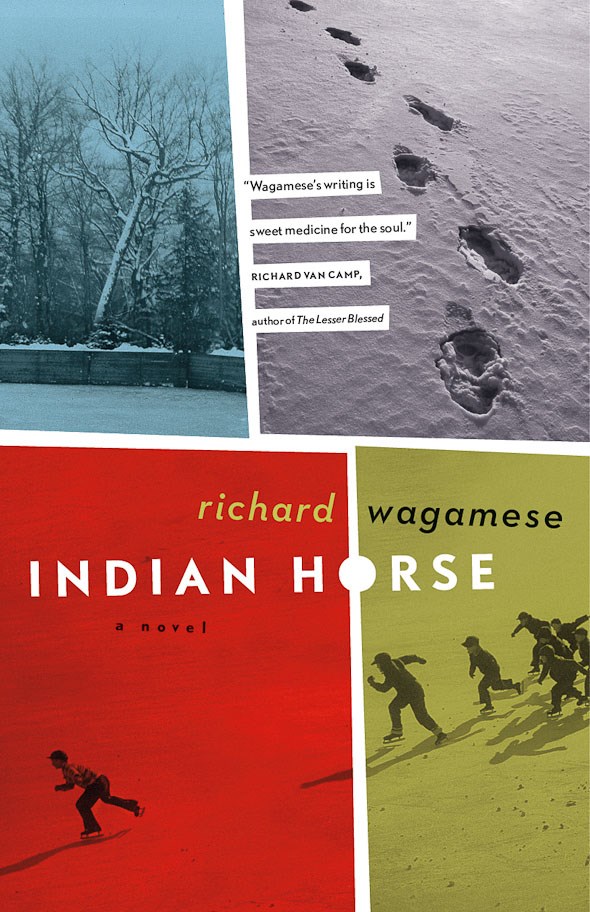

Waganese is an Ojibway from the Wabaseemoong First Nation in northwestern Ontario who has called British Columbia his home for close to a decade. He's in town to talk about his latest novel Indian Horse (Douglas & McIntyre) and, perhaps more importantly, to join 14 other recipients at tonight's National Aboriginal Achievement Awards Gala where he will be honoured with the 2012 award for achievement in media and communication.

Indian Horse is the story of Saul Indian Horse, himself a northern Ojibway. He is also a residential school survivor, a former hockey superstar, and an alcoholic. When we first meet him he's been at The New Dawn Centre for a month, after six weeks in a hospital. "The longest I've been without a drink for years, so I guess there's some use to it," he admits.

Finding it difficult to tell his story in the sharing circle at the treatment facility, Saul gets permission to write it down instead, taking us on his journey of remembrance and revelation.

Indian Horse is Wagamese's twelfth book and in it, as with his previous work, he examines the themes of abuse, displacement, and cultural alienation. There is also, however, a lot of joy when Saul is immersed in his means of escape, hockey.

Saul keeps his emotions in check throughout much of the book. It was quite emotional for me when he was matter-of-factly listing the abuses he witnessed at St. Jerome's. What was your thinking when you were writing that section?

Well, you know, I'm the 2nd generation that has been affected by residential school experience in my family and so beyond the trauma that my mother and my aunts and my uncles and my grandparents experienced they kind of tranferred that onto me when I was a baby. So I carry the same kind of trauma. As my life progressed I was put into situations where I encountered my own trauma, so I had a nest of it anyway that had been passed on to me, and fed to me as an infant, and then my own life experience added more onto that. So I understand how it feels to go through your life with your emotions tightly reigned because there are times when the abuse and the shocking nature of that abuse is so raw that you can't fathom letting go. You can't imagine the possibilies that would happen if you just let go. And it feels far safer to just hold tight to things and treat everything matter-of factly than it does allow yourself a certain degree of emotional freedom to maybe just let something totally ignite.

So that's played very real in the novel. And so when he looks back at all of those things he sees himself as a 9- or 10-year-old boy witnessing these horrendous things that are happening to the people and his friends around him. At that part of the book he's still doing that. He's still really holding onto the reigns.

Because at that point of his story telling he is still in the early stages of his therapy.

Yes. It's still too raw. It's still too overwhelming and he can't see any other way. He knows he has to release it, but he can't just uncork it and let it all pour out. He's got to really control it. I know how that feels and I know that it's a real and valid emotional response. Even though it's non-emotional, it's still an emotional response because you're choosing to be stoic or hard or aloof or whatever. You're still making that choice. That's where he's at.

I think what gives the book its particular resonance is that it rings true for people. They can understand that feeling. "Yeah, I just wouldn't want to let it all out at once."

Saul gets immense joy from playing hockey and for a long time he plays it his way, refusing to fight back, ignoring the taunts, but he finally gives in to the racism, he gives the people what they want. It's at that point that he seems to gives up on his true self. And the joy goes.

I think that everybody who has experienced some form of abuse that translates itself into trauma has also found the antithesis of that. There's something that brings them incredible joy and a feeling of freedom. Whether it's a sport, whether it's an activity, whether it's just walking on the land or whatever it might be that allows you to completely dissociate from your normal frame of reference. And it feels wonderful. And you come to revel in that like he does with hockey. You come to revel in it. It becomes an extension of yourself and it's a really, really personal sacred kind of joy. And you'd do almost anything to protect that. And he starts to see the obdurate face of racism thrust at him all the time and what he sees or what happens is that it touches the core of anger and rage that he has in himself over the things that have occurred in his life. Because he's never let himself just go out on the land and screeeam that his cultural and traditional and family way was destroyed. Never allowed himself to scream that his brother died of tuburculosis while they were doing rice harvesting. Never allowed himself to just vent completely. He always just stored it in there. When racism confronts him in the game and he gets constantly challenged and taunted it's like he finally finds an outlet, some place that "Okay, I can finally let this go here."

And it will be accepted. "It's what they want. They want me to act this way. They want me to be violent. And so I'll give them what they want."

Yes. And he thinks "And my payoff is that I get to take the stopper out of all of this stuff." And again I have a lot of personal experience of knowing how that feels, of finding that thing that sustains immaculate release and really wanting to protect it. And finding an incident or certain instance of a person that touches that nerve and they become the focus of all that stored negative energy. And for a long time I could convince myself that it was them or that circumstance that was the impetus or trigger for that emotional release and I didn't know until after therapy that it was the original incident and it was just this person that represented that same kind of emotional claw and I was wrapped into that and not to the personal circumstance and that's what happen to Saul in that release of that hold he has on himself. It finally just bursts.

Richard Wagamese joined authors Anne Degrace And Robert Hough at the inCITE reading series this past Wednesday, reading from his new novel Indian Horse and taking questions from the audience.

Richard Wagamese joined authors Anne Degrace And Robert Hough at the inCITE reading series this past Wednesday, reading from his new novel Indian Horse and taking questions from the audience.

There seems to be in your writing, and in your own personality, a sense of joy and hopefulness, despite all the bad experiences. Do find that sometimes it's hard to find that joy or is it just a part of who you are?

It often was (hard to find) for the majority of my life. But I discovered that my trauma isn't a life sentence and that I can find ways and means and techniques and skills to harness it. When I'm triggered, things come up, and I feel all of that old pain, all that anxiety, the desire to just bolt, that I can harness it. That's a really joyful understanding. If I'm talking to my wife and she says something or there's a tone and it automatically kicks in, somehow I can stop myself and say "It's okay. It's 4:30 in the afternoon on Tuesday. It's 2012, not 1962. Okay. Here I am."

How did you get into writing?

That was my "out." When I was small I knew that things were messed up. I only had to look around myself at five and see that the world was every other shade than brown. And I was the only brown thing in my world.

How old were you when you went into foster care?

I was a toddler, but when I finally got conscious I was five and that's all I knew. I was the brown one in the picture. So I just kind of understood that. I looked around myself and saw foster brother, foster sister, foster mother, foster father, foster grandparents. Who are these people? They're not from where I'm from. So I always felt lonely and out of place, so I would sneak away into the bush and write stories about what it would be like if I was with my family. And we were on horse riding expeditions and we would go fishing and I would write stories about that. And I was creating an alternate reality to the one I was living in. So even back then I realized that writing had an ability to not only make things a little easier for me but I could create these places and people that I could kind of come to believe in and that could help me get through something. So I used writing way back then as a ways and means of coping.

When I got older I was a journalist, from 1979 - 1992. Radio, TV, and newspapers. And while I was at the Calgary Herald, I read everything. I was a voracious reader and still am, and so I had all these people that I used to adore the way they worked with the language. I carried this hope that maybe I could do that too. But here I was writing as a journalist, and it's great writing, it's a great form of expression, but it wasn't stories. There were all these facts laying around that I had to pick up all the time and assemble them. And I wanted to try and just imagine something. Can I do that?

I remember sitting at my desk at the Herald and I was working on this feature piece and I felt something. It was almost like getting nudged in the ribs. And I was "What was that?" And I kept on working kept on working and I got another nudge in the ribs. I thought, "There's something going on here." And I put up with that for about 3 months and then I'm at home one night and I felt really, really homesick. I hadn't been home for a while. I'd been working really hard and I missed the sound of my own people talking. I couldn't phone my mother because she doesn't have a phone and in order to get her to the phone somebody would have to go and walk across the reserve and walk her back to the band office and it was going to be impossible. And there was that nudge in the ribs again. So I sat down at the typewriter (laughs) and I just started typing in the voice that I wanted to hear. And I was just writing and writing and it felt so good because I could actually hear it. And that was when I started to write my first novel (Keeper'n Me - 1994) and I realized as I was writing it there is so much more power in that act of creativity. Because not only did I calm my homesickness but suddenly I was launched into this great story. And I thought, "I've got to follow this and see what I can do." I eventually left the Herald so I could finish the book and the book became my first novel.

So writing has always been right there. For a long time when I drifted and I was trying to figure out what I wanted to do and what I needed in life I was always drawn to words and language. So I guess the call to be a writer was underneath all that. It was just a matter of getting myself ready.

What brought you to B.C.?

I came out here in 2002 and I just needed to go somewhere where I had no history. I just kind of needed to go somewhere where I could just be myself. I was between books and I was afraid that I wasn't going to get another idea. I was afraid that my inspiration well had dried up. And I thought, "I know what I'll do." And my alcoholism told me that if I took a geographical cure, things might be better. So I just followed that and came out here. The upshot of that is that they are better. Since moving to BC I've hit my stride as a novelist and as a journalist. I've written and produced more in the 9 or 10 years I've been out here than in all the other years before that. I've been publishing for 18 years and I've finished 12 titles. But the bulk of that has been since 2002.

The other thing is that I met Norval Morrisseau in about 1986, and we spent this glorious time together when he shared a whole bunch of traditional stories with me and talking at a really good level. And he told me when I was leaving "There's going to come a time in your life, I don't know when, I can't see it that clearly, but there's going to come a time in your life when you're going to need to go and live by the Great Water." And I never forgot that. And I was looking for some place to go and I'd been out here but never lived out here, out by the Great Water. It seemed just true. And so I came out here and sure enough I needed to be here.

You lived in Vancouver until 2007?

Yes we lived at Hastings and Boundary, and then in 2005 we found our place in the mountains and we commuted for a year and a half, and in 2007 we moved up there (Kamloops area) full-time.

It's a different climate there, both geographically and culturally.

Yeah. I think the most important thing is that I really needed proximity to the land and there I'm 1500 steps out of my back door and I'm in the mountains and I can walk up a logging road and just disappear for a while, wherever I want to go back there. And you can sit on a log or on a rock or lay in the grass under a tree out there and just feel all of it. And drink it in to you. And I realize how much I really actually needed that as a part of my daily existence. Since I've been there it's been really amazing.

Is that one of the reasons why you started offering live-in writers retreats?

Last summer was the first time we did that and we're going into our second summer. We still have bookings. (He leans into the microphone and repeats) We still have bookings to make for this year.

I don't know whether that was it so much as really recognizing how valuable the storytelling tradition and its teachings were to my development as a writer. And I wanted to give that away again because it was so important. I'm a guy with a grade 9 education. I've never been back to school since then. I've never taken any courses since then, and I've done all this. Honorary doctorate, National Aboriginal Achievement Award, 12 published titles, projects in every avenue of media, and I've done that with a grade 9 education. And the thing that enabled me to do that was when I found my people again and I spent time with traditional teachers and traditional people they were the ones who told me that my role and my responsibility in this reality was to be a storyteller. And I asked them "Well, how do I do that?" and they said, "Well, we'll tell you. You come to us with questions and we'll teach you." And they taught me the techniques and guiding principles of storytelling and they said, "Okay, now. Go do it."

And without any training, without any courses, I became a print journalist in 1979 because I rewrote 5 stories from the Globe and Mail for a native newspaper. They said, "Here's the stories. Rewrite them and we'll see what you can do." So I took these stories and I rewrote them on a typewriter and handed them in. And they said "That's pretty good writing. You're hired."

And that was my first experience as a professional writer without any training or experience. It was all based on the guiding principles of traditional story telling, and I've leaned on it ever since. And I know how empowering it is to start from that foundation and work your way through and I wanted to give people the opportunity to go through that, because not all of us can go to a traditional teacher or traditional medicine person and be guided and gifted that way. This is one way of giving back.

Having people come and stay with you for five days gives them the opportunity to have the stillness in their life to be more open to the teaching.

Yeah, because a big part of the process is going out on the land every day. So we go out and we walk and we sit and we meditate and we talk and we drink in that energy. And then we come back and we open the channel and use that energy to create. Because that's what you do. That's what you do. You become a part and an element of that continuous, eternal wheel of creative energy in the universe. That's the fact, Jack, that that's what's happening right now. You and I are sitting here and what's happening is that continuous wheel of energy is spinning and spinning. And when you're out on the land it's the purest form of contact because there's no concrete, there's no distractions. You're there and if you're directed you can find it in yourself. You can connect to it. And when you connect to it and you come back and you try to work with it as a writer or a storyteller amazing things happen. Because it's beyond you. You are actually surrendering all your worldly and physical stuff to that spiritual wheel of creative energy. And when you work at it amazing things happen.

(Many people) learn how to be a writer with their mind. I taught this process at UVic last year and I told my students, third- and fourth-year students, "You have to be out of your mind if you want to be a successful writer. You have to be out of your mind." And they went "What??" And I said, "You have to be out of your mind" (he motions away from his head) "and you have to be in here" (points to his heart). "And you have to feel that well of experience that you have. If you want to write something about something you have 23 years of experience on this planet. That's your frame of reference. That's where your authentic voice comes from. From that 23 years of all your unique and personal experience in relationship with this reality. That's where your 'stuff' is.

"And if you get into that, and you feel it and you intuit it, that's where you're authentic voice comes from. So we're not going to talk about filling your head with more theorems and paradigms and exercises. We're going to get out of your mind and into another area and you'll see your creativity just zoom exponentially."

And it did. And that was nice.

So, this National Aboriginal Achievement Award...

Yeah, wow, eh?

When did you find out you were going to receive it?

It was last August, which is weird enough, but then they said, "You can't tell anybody until November." And my response was "You realize you're talking to a known blabbermouth. I get paid to shoot my mouth off. You're telling me I can't say anything for three months?"

Ever since it's been announced, everybody I've talked to about it has said "How does it feel?" And you know it's not so much about how I feel about it personally. I think the greater energy should be directed toward what does it say to First Nations young people across this country. And in my profile that's shown at the Gala on Friday night I talk about where I have come from. That I've been homeless, and I've been an alcoholic, and I've been a drunk and I've been all of these things in my life, and I only have a grade 9 education but look where I am now. Because I have the ability to dream, and the ability to discipline myself and work really hard to make that dream come true. And here I am today, receiving this national honour.

So if that's possible in my life, what does it say for yours? That if these dreams can come true for someone with my experience, you can do the same thing too, as long as you choose to dream really big and just go for it. And that's the important thing. And that's where I feel honoured the most, to be able to represent that.

Richard Wagamese is one of 5 British Columbians being honoured tonight at the National Aboriginal achievement Awards gala at Queen Elizabeth Theatre. Other local recipients are Richard Hardy (K’omoks First Nation) for his achievements in the Environment & Natural Resources; Northern Dene Grand Chief Edward John for his political work; and wheelchair athlete Richard Peter (Bear) of the Cowichan Tribe First Nation, who has represented Canada at four Paralympic Games and will compete at the upcoming London Games. Receiving this year's Lifetime Achievement honour is Senator Gerry St. Germain, a Manitoba Métis who has long called B.C. home.

The sold out gala will be broadcast nationally on Global TV and Aboriginal Peoples Television Network (APTN) on Friday, April 13, 2012.