March 11, 2011: A reporter with the Iwate Tokai newspaper is swept by a surging tsunami at the port city of Kamaishi, in northeastern Japan, after a magnitude-9.1 earthquake. Toya Chiba, who was shooting photos when the tsunami struck him, survived and found himself only suffering scratches and bruises after being swept away for about 30 metres. Photograph By THE ASSOCIATED PRESS

March 11, 2011: A reporter with the Iwate Tokai newspaper is swept by a surging tsunami at the port city of Kamaishi, in northeastern Japan, after a magnitude-9.1 earthquake. Toya Chiba, who was shooting photos when the tsunami struck him, survived and found himself only suffering scratches and bruises after being swept away for about 30 metres. Photograph By THE ASSOCIATED PRESS

To travel through the Japanese prefecture of Iwate is to have a window on coastal British Columbia’s possible future. Seven years ago today, Iwate was rocked by the kind of violent earthquake and tsunami that are one day expected to hit coastal B.C.

Iwate, in which Victoria’s sister city Morioka is the capital, was the hardest hit prefecture of the 2011 Tohoku quake, the fourth-greatest magnitude quake ever recorded. Iwate endured the initial shock of that magnitude-9.1 shaking, and ensuing tsunami waves that reached 40.5 metres, and has steadily rebuilt.

Therein is a lesson for the Island and Lower Mainland. After what could be calamitous shaking and flooding — destroying much of Victoria’s brick-and-mortar Old Town, liquefying the ground beneath the Empress Hotel and drowning Tofino — the reconstruction will commence. It always does following a quake. It will take years, hundreds of billions of dollars and much hard work, but life will return to normal.

Iwate is living proof, as it has rebuilt following an event that shifted the Earth’s axis by up to 25 centimetres. The impact of the quake was so great that it shoved Japan’s main island of Honshu 2.4 metres to the east.

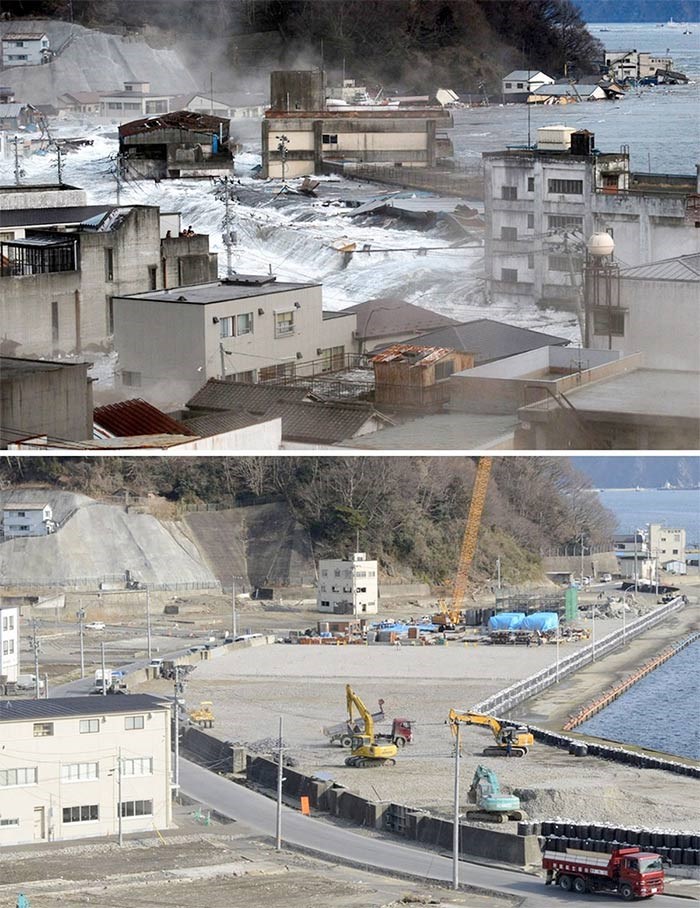

These photos, taken March 11, 2011, top, and Feb. 27, 2013, show the harbour area of Kamaishi, in JapanÕs Iwate prefecture.

These photos, taken March 11, 2011, top, and Feb. 27, 2013, show the harbour area of Kamaishi, in JapanÕs Iwate prefecture.

A large degree of normalcy has returned to Iwate. The prefecture will be among the 12 venues across Japan for the 2019 World Cup of rugby when the 35,000-population coastal city of Kamaishi hosts two opening-round pool games at the poignantly named Recovery Memorial Stadium.

An official post-quake recovery project, it is built on the former site of two schools that were destroyed by the 2011 tsunami. Its seating capacity is modest at 16,000, with 6,000 permanent seats to remain post-World Cup. Despite its size, Japan’s smallest 2019 World Cup venue is the most compelling.

Much of the city was destroyed, 888 people lost their lives in Kamaishi in 2011, and 152 are still listed as missing. It is part of the total of 4,762 who died in Iwate, with 1,122 still missing and nearly 16,000 across Tohoku (the regional name given the six prefectures that make up the north end of Honshu), with more than 2,500 people still unaccounted for.

“The stadium and World Cup games are a symbol of recovery,” said Keisuke Shirane, president of the Iwate Rugby Football Union, and head of the organizing committee for the group games to be played in Kamaishi, a city with a legendary pedigree in Japanese rugby as home to the former seven-time national championship club.

“We suffered. But now we have rebirth. We were down to rubble. Hosting the World Cup games shows we are no longer just reconstructing. It means we are past that and now we are advancing.”

Canada, which has participated in every previous World Cup, will play in the final qualification tournament in November for the chance to advance to the 2019 World Cup. It if does, Canada will play its final Pool B game at Kamaishi Recovery Memorial Stadium on Oct. 13, 2019, against the yet-to-be-determined Africa 1.

Construction continues on the main grandstand of Recovery Memorial Stadium on a snowy day in February. – Cleve Dheensaw

Construction continues on the main grandstand of Recovery Memorial Stadium on a snowy day in February. – Cleve Dheensaw

Because the Canadian national team is located and trains on Vancouver Island, at the Rugby Canada Centre of Excellence in Langford, and because of Victoria’s connection to Morioka, the Times Colonist was invited by the prefecture of Iwate to take part in a sponsored series of tours for world media to highlight its recovery from the quake and its preparations for the 2019 World Cup and as a pre-Games training venue for the 2020 Tokyo Summer Olympics.

There is another quake connection between B.C. and Iwate. One of the main reasons we know about the estimated 8.7- to 9.2-magnitude Cascadia earthquake in 1700 off Vancouver Island, the seventh-greatest in history in terms of magnitude, is because of Japanese tidal records kept in Iwate.

Experts in the field say our time is coming again, and another Big One is due. If so, we will go through the sort of rebuilding Iwate has gone through over the past seven years. There are many lessons to be learned.

To see the level of ongoing construction in Iwate, especially in the coastal areas that were hardest hit, is to bring home the magnitude of the reconstruction coastal British Columbians will face. Japan estimates the rebuilding costs from the earthquake and tsunami to be $340 billion Cdn.

Japan’s recovery has been paid in part by a national reconstruction tax. At that sort of staggering cost, it means other government services and programs across Canada might have to be sacrificed or curtailed in the massive national effort it would take to rebuild communities such as Victoria, Vancouver, Tofino and Port Alberni.

It will be life-altering on so many personal levels, as well, even after the shaking stops and the waters recede.

Iwasaki Akiko, proprietor of the Houraikan Inn in Kamaishi, survived the tsunami by landing on the roof of a bus after being swept away by the rushing waters. Asked if she had any words of advice for residents of coastal B.C., she stoically replied: “Escape, survive and start reconstruction.”

She continued: “Kamaishi is an example of how we live on this disaster-prone Earth. Be prepared not to be helped but to help others.”

New sea walls have gone up in Iwate. They now gird the coast at key locations in the prefecture. Highways and rail lines have been rebuilt, and the work continues, with road-construction-crew flaggers still a growth occupation in the prefecture and heavy equipment still dotting the landscape.

The two schools in Kamaishi destroyed by the tsunami have been rebuilt across a new highway which replaced the roadway that was destroyed. On their former site rises the stadium that will host games next year in the rugby World Cup.

“The impact of the World Cup is larger emotionally than financially,” said Saski Tomoaki, manager of Recovery Memorial Stadium.

“The laughing voices of school children once echoed on this site [all survived by holding hands and following their teachers to higher ground]. Now, sports games will be played. Hosting the World Cup has given us confidence in ourselves and shows to the world that we are ready once again to celebrate. It is not all about the infrastructure. When in our hearts we recover, that is when we will be truly recovered.”

Saski Tomoaki, manager of Recovery Memorial Stadium, holds an artist’s rendering of what the completed facility will look like for the 2019 World Cup of rugby. – Cleve Dheensaw

Saski Tomoaki, manager of Recovery Memorial Stadium, holds an artist’s rendering of what the completed facility will look like for the 2019 World Cup of rugby. – Cleve Dheensaw

The soaring spirit of rebirth can be felt everywhere in Iwate.

“After seven years, we can move forward while remembering how cheerful and warm our hometown and home prefecture remained through this whole event,” said the heroic Kamaishi innkeeper Akiko, who was initially safe after running to higher ground, before coming back down to help others.

“The recovery will be complete when we stand on our own feet and start walking by ourselves.”

That process began right after the earthquake and tsunami hit.

Aala Kamzali, a French travel blogger based in Japan, came up from Tokyo and volunteered to help the reconstruction in the aftermath. He, like so many others, felt compelled to do so.

Kamzali saw surreal sights, such as a car stuck in the second-storey window of a house. Yet there was something in the spirit and resolve of Iwate and its citizens that deeply moved him: “The people had hope. They lost everything. But they were not crying or feeling sorry.”

“The first business that reopened did so right the next day,” said Kamzali.

“It was a dentist’s office. Everybody hates dentists, right? But everybody loved this guy.”

These people are made of tough stuff. It is the type of mettle that one day we might have to display if we face rebuilding the Empress, the legislature, Old Town and much of downtown Port Alberni.

“We live in an area where we get earthquakes and tsunamis, but it’s in our DNA to survive in this environment,” said Akiko.

If it requires clinging to the roof of a bus, so be it.

“I live by the sea by choice because I enjoy it. The ocean is good. It is not bad. We’re part of nature. But nature wouldn’t be the same without us.”

Tomoaki, the manager of Recovery Memorial Stadium, proudly states the facility is the only one being built from scratch for the 2019 World Cup of rugby.

“Kamaishi was devastated in 2011. We asked ourselves: How do we pay back the goodwill we received in the recovery?” said Tomoaki. “The opportunity came with the World Cup to help in the rebuild.”

The $47.7-million Cdn stadium was funded with $24 million from the federal government and $12 million through a national sports lottery with the remainder coming from the city and prefecture.

There is another lesson for B.C. cities. The weight of the post-quake and post-tsunami recovery will fall on federal programs. But we will also be responsible for some of the rebuilding at the provincial and civic levels.

Much of it will be grimly necessary. It will also be psychically liberating.

“Hosting the World Cup gives us a feeling of confidence in ourselves again and shows we are ready to celebrate,” said Tomoaki. “I am proud of this stadium for that.”

Koichi Matsuda, now with the Tourism Division of the Iwate prefectural government, was with the prefectural government in another department when the shaking started in his inland Morioka office on March 11, 2011.

“The length and strength of this one was not usual. We felt the difference,” said Matsuda.

The response was immediate.

“We knew we had about 30 minutes to have all prefectural government departments prepared for the tsunami,” said Matsuda, a father of a young family, who was then in charge of several government units co-ordinating the response to the disaster.

“There was a definite focus. We had the emergency manual in front of us right away. We were not panicking. We were responding, almost immediately.”

That is another example for B.C. to follow: Don’t be scrambling in the precious minutes after the shaking starts. Know what to do seemingly instinctively, but by design.

So it came as a blow to the Japanese psyche that a prepared, modern nation could still lose nearly 16,000 people to such an event. The TV images of the best helicopters money can buy, hovering helplessly over stricken areas, is still burned in the national consciousness.

And no manual is perfect: One of the higher grounds recommended for evacuation in Iwate was overwhelmed by the tsunami, and people died.

“You can never prepare perfectly,” lamented Matsuda.

Monument to the quake/tsunami dead at a shrine in Iwate prefecture. – Cleve Dheensaw

Monument to the quake/tsunami dead at a shrine in Iwate prefecture. – Cleve Dheensaw

His advice to Islanders and other British Columbians on what to do during the harrowing moments of the quake and tsunami: “Use your own judgment.”

But that’s another story. This one is about the recovery that will have to follow the Big One in B.C., and the Japanese example.

“We had a 10-year plan to be at full recovery and are right on track with that timeline,” said Matsuda.

“We want it completed before the Tokyo Summer Olympics, and Iwate is working with Tokyo 2020 on one of the themes of the Olympics being on rebuilding from 2011.” And people are returning. Preliminary numbers from Iwate prefecture show that nights spent by international guests rose to 188,310 in 2017 from the 32,140 in the quake and tsunami year of 2011.

Greater Victoria, as a major Canadian training hub for Canadian Summer Olympians and sister city to Morioka, will play a role in that rebound. Already, two sports heavily associated with the Island, rugby sevens and wall climbing, have come to an agreement to hold their pre-Games training camps in Morioka in 2020 before taking the bullet train down to Tokyo for the Summer Games. Other Island-based national sports governing bodies could follow suit in using Morioka and Iwate as their training bases before the 2020 Olympics.

“The reconstruction has already peaked, and work is declining steadily,” said Matsuda, proudly.

“It feels like it’s already almost there. The local people love their homeland, Iwate, and are proud of the reconstruction.”

The people of Iwate have proved that, while nature will have its say, they are made of sterner stuff. Just as one day we will have to prove it.

cdheensaw@timescolonist.com