Scotland has always been a place steeped in myth and magic, and nowhere is that more evident than in the Highlands. While Edinburgh—with its breathtaking Royal Mile— and Glasgow—with its cutting edge arts and music scene—inevitably compete for the attention of most tourists, the North is where the true heart of Scotland lies. At least, that’s what the souvenir tea towels tell me.

Black Isle Bar (Rob Mangelsdorf/The Growler)

Black Isle Bar (Rob Mangelsdorf/The Growler)

The rugged wilds of the Highlands are home to elusive lake monsters, Neolithic ruins of long-vanished ancient civilizations, fairies, castles and some of the finest whiskies on Earth (which might explain the vivid imaginations of the locals).

Not surprisingly, there’s also a growing craft beer movement in the North, led by world-beaters Brew Punk from Aberdeen. Traditional malty cask ales have seen a resurgence alongside hopped up iterations of North American craft standards, with many breweries combining the two styles to great effect. Indeed, the crystal clear waters of the Highlands are not only well suited for whisky-making, but brewing as well, making the region a must-visit for fans of the fermentable arts.

Inverness

The Malt Room (Rob Mangelsdorf/The Growler)

The Malt Room (Rob Mangelsdorf/The Growler)

Any visit to the Highlands usually starts in the ancient city of Inverness, since literally all roads in Northern Scotland lead there. The city sits at the geographic centre of the region, and has served as its administrative, commercial and cultural capital for millennia. Flanked by the rugged wilderness of the Cairngorms and the Great Glen to the south, its Victorian gothic spires overlook the mouth of the River Ness, flowing north towards the calm, shallow waters of the Moray Firth and the frigid windswept North Sea beyond it.

I wanted to get my bearings so I made my way through the narrow alleys of the Victorian Markets to The Malt Room, arguably the best whisky bar in Northern Scotland and certainly one of the hardest to find. This tiny modern shrine to whisky (both scotch and Japanese, interestingly) is the perfect starting point for any serious exploration of the indigenous beverage scene.

Bar manager Jack Lowrie is an affable Invernesian with an obvious passion for whisky, and on this particular night, his 25-seat bar is playing host to a tasting session for legendary Speyside distillery, The Balvenie. The crowd is boisterous, jovial and refreshingly unpretentious—such is the character of the Highlanders.

As Lowrie excitedly pours me dram after dram he explains that categorizing whisky by region is difficult, given how varied the offerings are.

“Generally, Speyside whiskies are unpeated, very smooth and easy drinking,” says Lowrie. “Highland whiskies have all of that, but tend to have a bit more spice.”

That being said, distilleries located right next door to each could easily taste completely different. Take the example of Highland Park and Scapa. Located a few hundred metres away from each other on the Orkney Islands, the two whiskies couldn’t be further apart in flavour: Scapa is light and briny while Highland Park is bold and smoky.

The one thing Highland whiskies do have in common is respect for the craft. There’s no cutting corners, just patience, attention to detail and the constant pursuit of perfection. It’s all very kaizen, which is perhaps why the Japanese are so smitten with scotch.

Heady from the Highland hospitality, I ventured around the corner to Black Isle Brewing Co.’s flagship gastropub on Church Street. Here you can sample 26 different organic beers from the local craft brewery alongside some top-notch nosh, like the Red Kite Amber Ale (4.1% ABV). Exceptionally well balanced with jammy biscuit and subtle roast notes, it pairs nicely with one of Black Isle Bar’s wood fired pizzas. Much of the ingredients used at the pub are grown and raised at Black Isle’s own organic farm and brewery, just eight miles from Inverness.

The Black Isle and beyond

Let it be known that the Black Isle is neither black, nor an island—a more appropriate name would be the Green Peninsula, but I guess that doesn’t sound as cool.

Located down a single-track gravel road in the bucolic burg of Munlochy, Black Isle Brewing Co.’s brewery sits on a 140-acre certified organic farm where the Gladwin family has been making beer for 20 years.

Black Isle Brewery (Rob Mangelsdorf/The Growler)

Black Isle Brewery (Rob Mangelsdorf/The Growler)

For owner Michael Gladwin, the decision to go organic was one of environmental responsibility.

“The Highlands are a beautiful place, but man is doing a good job of making a mess of it,” he tells me as we walk through the massive modern barn that holds the brewery. “This is one of the most beautiful places in the world, so we have to protect it.”

That means producing electricity through biomass generators and, soon, by windmill, as well. Waste products like spent grain are fed to the sheep, cows and horses on the farm. Wastewater is treated and used to irrigate the rolling hills of malting barley, which end up in some of its own beers.

“We didn’t do this to just as a point of difference,” he explains. “We’re deeply concerned about the environment.”

Beyond the brewery, I follow the country roads that encircle the Isle pass through quaint farms and fishing villages, and past oddities like the Clootie Well. This rather bizarre pilgrimage site dates to pre-Christian times and is where the afflicted have come for centuries to tie tens of thousands of rags and cloths (cloots) to surrounding trees in a superstitious effort to ward off illness. The result is fascinating, creepy, and kind of smelly.

At Rosemarkie, chubby bottle-nosed dolphins, plump with blubber to keep them warm in the subarctic waters, rub their bellies on the smooth stones mere metres from shore. A short walk down the beach brings you to the 15th oldest golf club in the world, while the nearby ruins of Fortrose Cathedral are the final resting place of explorer Sir Alexander Mackenzie, the first person to cross North America by land in 1793. The Plough Inn has seen better days, but it’s worth a stop at this classic Scottish pub for a hand-pulled cask ale. Save some room, though, as a mile down Union Street, The Anderson offers a truly impressive selection of bottle-conditioned and vintage ales from all across Europe.

Cromarty (Rob Mangelsdorf/The Growler)

Cromarty (Rob Mangelsdorf/The Growler)

At the northern tip of the Black Isle is the tiny village of Cromarty, home of the Cromarty Brewing Company. Located on a barley farm above the village, the brewery itself doesn’t have a tasting lounge, but does have a bottle shop and runs tours on Saturdays. Thankfully Cromarty’s craft-inspired cask ales and bottled beers are available at pubs all over the Highlands. The Happy Chappy New Wave Pale Ale (4.1% ABV, 30 IBU) is a delightfully fruity, slightly nutty, easy drinking session ale packed with juicy New World aroma hops. Maybe it was jovial atmosphere at the Arisaig Hotel where I first sampled it, or the drams of Ardbeg the locals were buying the Canadian oddity at the bar, but pints of this hand-pulled cask ale were the stuff of nirvana, the very definition of “moreish.”

North of the Black Isle lies the Cromarty Firth, the body of water that separates it from the mainland and also serves as a staging area for the North Sea off shore oil rigs. At any given time, there may be dozens of these steel behemoths—some 30 or 40 storeys high and weighing thousands tons—anchored in the bay, waiting to be serviced and sent back out to sea, or on to the scrap yard. It’s an incongruous sight, but no less impressive.

In the summer, a tiny car ferry will take you across the narrow of Cromarty Firth to the oil town of Nigg (tide and weather dependent) in a few minutes, otherwise you’ll have to double back some 40 miles across the Cromarty Bridge to the south.

In addition to the oil industry, the whisky industry is also prevalent in this neck of the Highlands, with massive, mold-covered warehouses dotting the shoreline.

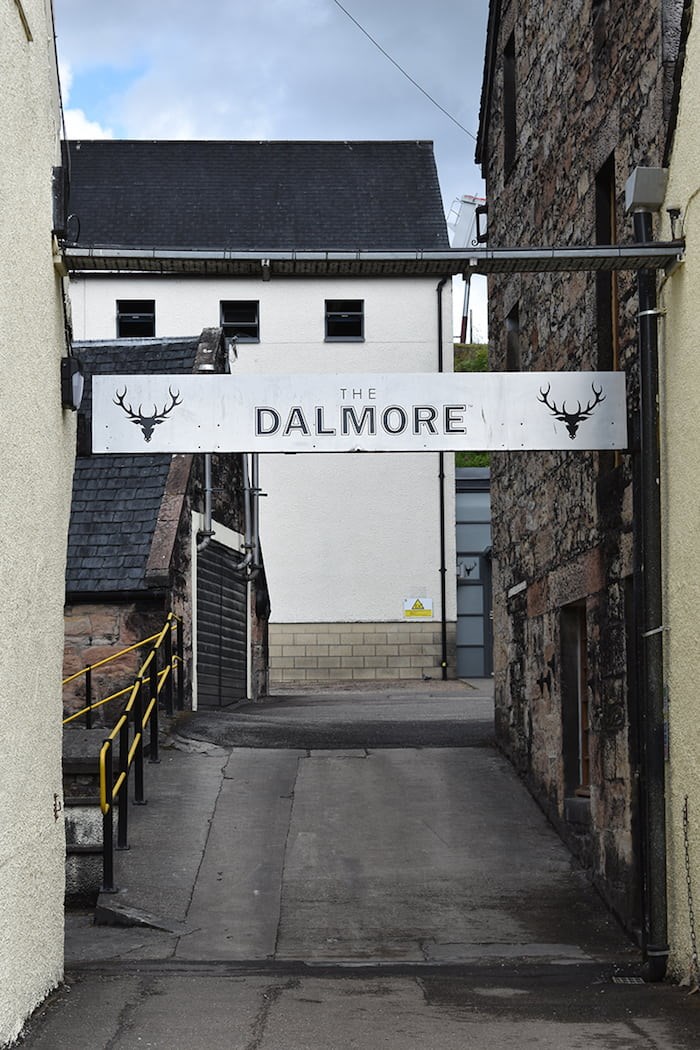

The Dalmore Distillery in Alness was founded in 1839, and operates 24/7 to produce more than 4.3 million litres of spirit annually—most of which goes to nearby blender and parent company Whyte & Mackay in Invergordon. The seaside distillery’s vast warehouses contain more than 65,000 casks of whisky, some dating as far back as 1969.

The Dalmore (Rob Mangelsdorf/The Growler)

The Dalmore (Rob Mangelsdorf/The Growler)

Like nearly all distilleries, Dalmore offers guided tours and ours finishes with some samples in its swanky circular tasting room. You can’t help but imagine Chinese billionaires, Saudi princes or Russian oligarchs choppering in here for their own private tasting and tour. Which apparently happens from time to time.

The Dalmore King Alexander III was a standout, with notes of toffee, vanilla, citrus, spice and chocolate after having been variously aged in casks of bourbon, marsala, madeira, cabernet sauvignon and sherry.

Up the road in the village of Tain is the equally historic Glenmorangie Distillery, also owned by Whyte & Mackay. Glenmorangie has been around since 1843 and is the scotch Scots drink most—in fact, it’s been the best-selling single malt in Scotland for the past 35 years.

The tour takes us through the distillery where the extraordinarily tall copper stills resemble a massive pipe organ, giving the airy oceanfront building the feeling of a cathedral. Certainly it’s a place of reverence and worship, and thirsty angels have long been suspected of hanging about.

I went home with a bottle of the Lasanta, a single malt aged for 10 years in bourbon barrels and finished for another two years in Spanish sherry casks. Smooth, rich and sweet, with flavours of honey, dark fruit, citrus and spice dominating—it’s little wonder it was named Best Highlands Single Malt at the World Whiskies Awards in 2017.

The Cairngorms

Cairngorms (Rob Mangelsdorf/The Growler)

Cairngorms (Rob Mangelsdorf/The Growler)

Heading south of Inverness now, I pass the site of the bloody Battle of Culloden in 1746 where the Jacobite Uprising was extinguished and the entire Highland way of life along with it. More importantly, it’s where the Season 3 premiere of Outlander takes place.

As I travel along the A9 motorway, it’s not long before all traces of civilization are left behind. This is the Cairngorms, Scotland’s massive national park, which offers that all-too-rare commodity in Europe: proper wilderness. Often in the U.K., what nature does exist is rigid and manicured, with man’s fingerprints all over it. Even the heathered glens of the Highlands only exist because all the trees that used to grow there were chopped down and never replanted.

But the Cairngorms is different. Here there are endless rolling peaks, surging rivers and thick forests of Scotch pine that will likely look very familiar to most British Columbians. And amongst it all, a distillery of all things. Just in case you forgot you were in Scotland.

At first glance, the Tomatin Distillery, 30 minutes south of Inverness at the edge of the national park, appears to be precisely in the middle of nowhere. But as Kirstie Eunson, Tomatin’s visitor centre supervisor explains, the distillery was purposely built in its somewhat remote locale because it has access to a quality water source and is on a major train line (and now, the A9).

Tomatin (Rob Mangelsdorf/The Growler)

Tomatin (Rob Mangelsdorf/The Growler)

“We think the softer water helps with the softer flavour profile,” says Eunson, who also has a master’s degree in distilling.

Tomatin is the new kid on the block of Highland scotch, having only been founded a mere 121 years ago, but in that very, very short time they’ve proven they can hang with the big lads. In the 1970s the distillery was the largest in Scotland, exclusively producing spirits for blending houses. However, a global downturn in the demand for whisky saw Tomatin go bust in 1986 before reopening a year later, this time producing its own single malt scotch for the first time.

The distillery still has a rustic feel, and has resisted the industrial automation seen in many other distilleries. Much of the work is still done by hand, Eunson says, and Tomatin even employs its own cooper to build and repair its wooden barrels.

“It’s part of the charm of the distillery, I think.”

Tomatin’s visitor centre is bustling on the day I visit, but I’m still able to snag a stool at the bar. I try a wee dram of Tomatin 18 and I’m enraptured by honey, oak, citrus, chocolate, happiness, the sound of a child’s laughter, a first kiss—it’s all in there. I wish I could afford to take a bottle home with me. Sadly, Tesco’s doesn’t carry it, either.

Further along the A9 and into the national park is the Cairngorm Brewery in the alpine resort town of Aviemore. If there is a brewing award given out in the U.K., it’s a safe bet Cairngorm has won it, multiple times. And while the branding might be a bit dated, the beer is beyond reproach. Trade Winds (4.3% ABV) is a delicious, complex, well-balanced cask wheat ale with elderflower. Smooth and slightly nutty, there’s notes of citrus, jam, biscuit, lemongrass and spice, all in perfect harmony.

The brewery offers samples and tours, and even does growler fills, which is still somewhat of a rarity in these parts. Despite being somewhat isolated in a town of little for than 2,000 people, Cairngorm’s tasting room is bumping when I visit. It’s just further proof that in the Highlands, even if you’re in the middle of nowhere, you’re never far from good drink.

The Fall 2018 issue of The Growler is out now! You can find B.C.’s favourite craft beer guide at your local brewery, select private liquor stores, and on newsstands across the province.