Ladysmith intermediate school principal Dionte Jelks was a world away with his family strolling a Victoria beach when his mother phoned on Sunday to say his younger brother and a cousin had been shot dead in Chicago amid violence stemming from protests over the police killing of George Floyd.

“I always dread phone calls when I look down and see they are from Chicago,” said Jelks, who left the United States at age 30 for a different life. “I hold my breath every single time.”

Having just bought ice cream with his wife Elizabeth and three sons Noe, 13, Jeremy, 12 and Kian, 7, Jelks was marvelling at the day’s beauty, the paragliders’ ballet in the skies, when he received two calls from his sister followed by one from his mother.

His mom’s voice quivered. “My baby is gone. I already lost one baby and now I’ve lost another,” he quoted his mother as saying. “I had no words to comfort her.”

On Monday, Jelks was still numb; he couldn’t cry. “I’m desensitized to the violence. I just have no emotions. My bank is empty.”

Jelks has one brother in jail. His other brother, Darius Jelks, 31, was with cousin Maurice Jelks, 39, as the two drove through protests and looting on the south side of Chicago.

“They were driving back to my mom’s house and they were stopped at a stoplight in the middle of a lot of looting,” said Jelks. “They were both shot in the car right there on the street in broad daylight.” He doesn’t know who killed them. “It could have been anybody.”

Systemic racism, prejudice, oppression were all reasons for why he moved to Canada from the United States, he said.

Jelks is not surprised by the video recording of George Floyd’s arrest in Minneapolis.

“It could have been me,” said Jelks. “It could have been anybody.”

Jelks recalls the day in Chicago he was walking to a friend’s house, his university registration papers under his arm, when police swarmed. They descended from alleyways and cars.

“The next thing you know police come out of nowhere with guns pointed at my face,” said Jelks “to yell at me to take my hands out of my pocket. I told them ‘no, I’m not going to do such a thing, you come take them. I’m not gonna get shot.”

His papers flew away.

In explaining this past week’s protests to his sons, he tells them the reasons people are protesting and why others are looting. He tells them how he had to work twice as hard to achieve the same as his white counterparts. He tells them that where he grew up, kids by age seven or eight are taught almost as a rite of passage what to do and not to do if police approach.

“Luckily my uncle sat me down at the time and told me exactly what to do, that if I was to pull my hand out of my back pocket I would have been shot,” said Jelks. “You never know which way it’s gonna go.”

Educators and parents need to teach their children to treat one another with respect — to treat others as you wish to be treated, he said.

Jelks earned a psychology degree and then an education degree.

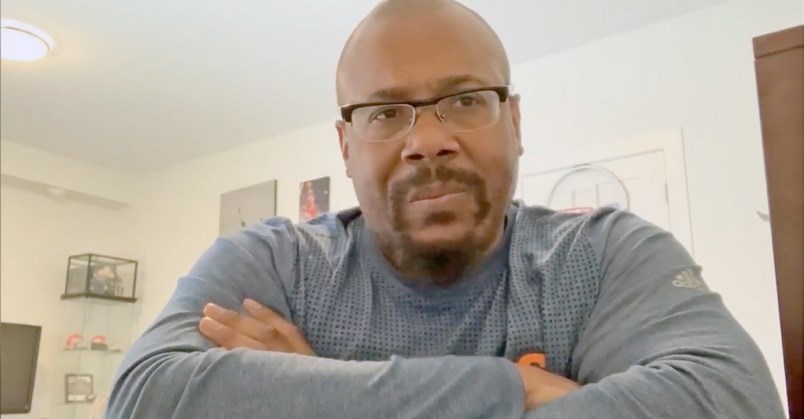

Dionte Jelks in a still from Facebook.

Dionte Jelks in a still from Facebook.He lives in Langford and commutes to his job at Ladysmith Intermediate. He coaches the Victoria Spartans football team, and before that Victoria minor football.

Amid the protests in support of #BlackLivesMatter, decrying police violence, Jelks said he walks a fine line on how to respond.

“I think people have the right to protest but I approach things in a different way,” said Jelks. “I like to coach sports and work with youth and by coaching show them that I’m a stand-up guy and I’m there for them throughout their lifetime.

“We have to reach the kids; when people are adults they’re set in their ways,” said Jelks. “My protest is in a different way. My protest is being with the youth and showing them a different way.”

“If you want to see change in the world, you need to be that change,” said Jelks. “We just have to continue to support and educate our younger kids because they are the change. I started with my kids and that’s been a change.”

On Sunday, Jelks sang a First Nations women’s warrior song for his mother, who will have to bury her son and nephew without Jelks’ help. He returned for the funeral of a nephew who died by suicide in October but won’t return amid the pandemic.

Instead, Jelks wants to bring his dead brother’s six-year-old son and his sister’s 11- year-old son to Vancouver Island to live with his family.

“At times, you know, I sit with my wife and I’m like ‘you know I should be there, you know, helping,’ but on the other hand you know I want to break the cycle and have my kids be raised the right way. It’s like a no-win situation and it just tears me apart all constantly.”

Read more from the Times Colonist