Karen Hodgson is just the kind of person I need to know. The two of us are making small talk and munching on potluck fare in the multipurpose room of a west side church. Between bites of chicken stew, white bean soup and vegan cupcakes, the conversation turns to gardening. I mention my plan to attempt growing food on my small but sunny balcony this year and Hodgsons face brightens. Make sure you get the biggest, deepest planters you can, and since youre south-facing, try heat-loving herbs like rosemary and basil, she offers.

For an aspiring gardener, Ive hit the jackpot. It turns out Hodgson runs a small business called Hotbeds that primes people for their first urban farming experience. You can also try kale, oriental greens and rainbow chard, she chatters on as I furiously take notes. The good thing about kale is its idiot-proof.

If Id placed a personal ad: neophyte greenthumb seeks urban growing expert, I couldnt have asked for a better respondent than Hodgson. And thats precisely the kind of connection Ross Moster hoped to facilitate when he started hosting a series of drop-in spaghetti dinners at his Kitsilano home about three years ago.

By bringing a few sustainably minded individuals together to share a meal now and then, Moster realized a couple of things were happening that had the potential to turn his neighbourhood into a greener, more socially cohesive community.

First, the dinners offered an opportunity for like-minded people to brainstorm, collaborate and maximize sustainability efforts, such as carpooling or composting, already underway in their hood; and second, the very act of eating together and using one stove to feed 10 or 20 people was actually making a tangible impact by reducing the communitys energy consumption.

That was the beginning of Village Vancouver, now a nebulous grassroots network of about 3,000 people across the city, all working on myriad sustainability initiatives under a premise so simple its almost difficult to comprehend: Getting to know your neighbours can save the world.

We have tremendous resources in our neighbourhoods. We just tend not to know our neighbours, Moster tells the 25 or so people attending the first official Dunbar Village Transition Town potluck and community visioning session at St. Philips Anglican Church.

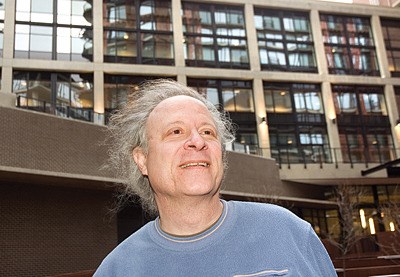

A snowy-haired boomer whose ponytail belies a past life directing a Los Angeles food co-op, Moster explains that Village Vancouver is part of the international Transition Network, a U.K.-based movement working to encourage communities to decrease their reliance on declining oil reserves by increasing their reliance on, well, each other.

The animating idea, says Moster, is that we need to acknowledge our current, energy-happy way of life is up against some pretty heavy threats from climate change and peak oil production, and well be feeling the impacts of those factors more and more in the coming years. But we dont have to live in crippling fear of the impending apocalypse. Rather, Moster and other members of the Transition movement are leading the charge to create self-sufficient communities that will be more resilient in the face of a climate-change induced natural disaster, or in the event that we can no longer rely on cheap and plentiful oil to keep the world running as we know it. And heres the trick: instead of focusing on the worst-case scenario, which tends to inspire people to build barricades and hunker down in basements, Moster and other Transition Network adherents appeal to peoples natural desire to live in socially vibrant communities. In Mosters experience, most of the time the ideal community just happens to be a green one.

The idea of creating community and Ive probably done at least 25 visioning sessions and every time it comes out the same when people describe their visions, even though the specifics might differ, its always a very low-energy lifestyle, he says. So to me, I try to be pragmatic, I look at how do we engage people. If talking about peak oil engages people, Im happy to talk about it. But my experience has been its a really important component of what were doing, but thats not what moves people to take action or get engaged.

The real motivation, Moster continues, comes when people discover just who it is thats sharing their building or their block and begin to create social outlets. Whether its potlucks, communal gardening or chicken coops, tool exchanges or car-free block parties, most of the ways we hang out with our neighbours also tend to lower our energy consumption and create self-sufficiency. The solutions are often right at our doorsteps, says Moster.

Its just that we often need a little coaxing to venture out and find them. Theres a desire on a lot of peoples parts to be connected in community, but I think one has to be intentional about it; it doesnt necessarily come easy these days because its not the message that we get from the media, he says.

Thats where Village Vancouver steps in. With nearly 1,000 registered users on its website, (VillageVancouver.ca) Village acts as a kind of Craigslist for the eco-community minded, or just plain curious. The site boasts an overwhelming array of working groups, events and discussion forums catering to interests ranging from the ultra-nichey (as in beekeeping, seed-saving or local currency development) to the relatively mainstream (childcare, affordable housing, car-sharing) active in neighbourhoods throughout the city.

Meanwhile monthly Transition Town meet-ups in various neighbourhoods offer another chance for people to make inroads in their communities. Our motto is: Talk to your neighbours, see what happens, says Moster.

Often, what happens is remarkable. For Nate Reister and Asia Warner, Village Vancouver is just an extension of what theyre already doing in a two-block stretch of Little Mountain around Quebec and 23rd. Were not really that involved, chimes Warner, who dropped into the Dunbar meeting to see a friend.

Its the understatement of the century. Longtime chicken aficionados, the couple keep hens in their backyard, a vegetable garden out front and are working towards keeping bees this summer. The same arrangement can be found at several residences down the block. Last summer the community took part in a two-block-diet experiment where a number of households contributed vegetables, eggs, compost and honey in a community initiative to build a local food economy. And Reisters page on the Village Vancouver site is a wealth of information on all things chicken-related.

But there is some truth to Warners comment. Building what has become an admirably self-sufficient community hasnt taken a Herculean effort. Its not about sacrificing, but rather celebrating abundance with friends and neighbours. The two-block-dieters havent given anything uprather, theyve gained.

Sitting around the long table at the Dunbar meeting, its clear Reister and Warners little chunk of East Van serves as an ideal many of these West Siders are hoping to reach in sleepy little Dunbar.

Its that kind of spirit that inspired the crowd here families with young kids, students, singles, even one anti-establishmentarian teenager to come out of the woodwork and meet the people in their community. Introducing herself to her neighbours, urban farming guru Hodgson recalls how she would have killed for a community like Warner and Reisters. I am kind of an East Van wannabe, she confesses. But instead of longing wistfully for that kind of all-too rare community connection, Hodgson says she is determined to build her own through Village Vancouver. After coming to a couple of meet-ups, Hodgson says suddenly, that goal doesnt seem so far away. I went to the first meeting and found a bunch of like-minded people. It was like, ah, Im home.