The average rent of 68 privately owned and operated single-room-occupancy hotels in the Downtown Eastside shot up by $139 in one year since a Downtown Eastside anti-poverty advocacy group conducted a similar study in 2016.

That put the price of monthly rent in 2017 at $687, leaving tenants collecting $710 in welfare with $23 left to spend each month on food and other necessities, according to a new report released Monday by the Carnegie Community Action Project.

“This is the 10th report I’ve co-written, and it’s never been this bad,” said Jean Swanson, one of the spokespersons for the Carnegie group. “We need governments to spend billions of dollars on social housing — that’s what we need.”

The average rent in 2016 calculated by members of the Carnegie group was $548 per month. Each year, members collect information by visiting hotels. They visited 84 private hotels last year and obtained rent information from 68 of the buildings, which had a total of 2,919 rooms.

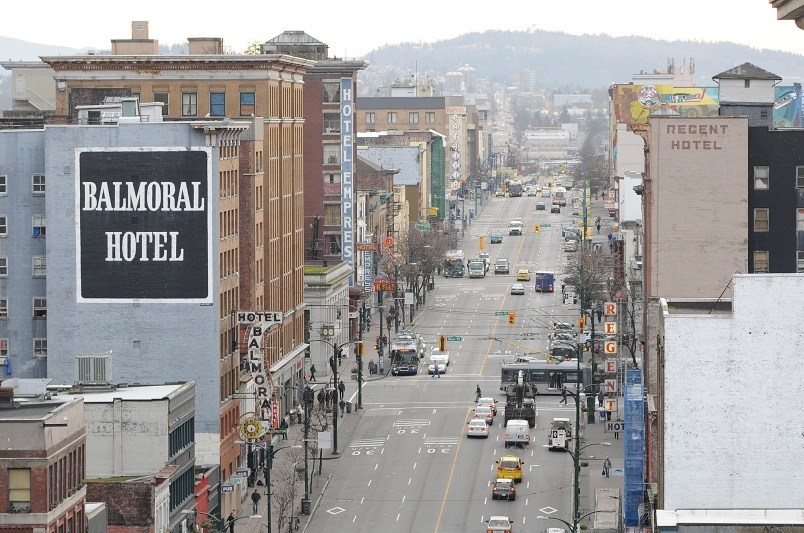

Some of the hotels visited in the research included The West, The Metropole, The Lotus, The Regent, The Astoria, The Cobalt and The Ivanhoe.

The average rent is even higher in what the Carnegie group described as the “10 fastest gentrifying hotels.” The Low Young Court is at the top of the list at $1,800 per month, followed by the Georgia Manor at $1,600 and Argyle Hotel at $1,450.

Rent increased during a year in which the group also counted more than 300 low-income units lost in the Downtown Eastside because of closures or renovations. An additional 157 were lost at the former Quality Inn hotel on Howe Street, which served as temporary housing for many Downtown Eastside residents.

One of the biggest hotels to close in the Downtown Eastside was the 168-unit Balmoral Hotel at 159 East Hastings St. The city closed the dilapidated building because of unsafe conditions. The city-owned Roddan Lodge at 124 Dunlevy St., which had 157 units, was demolished to make way for a new building. Another 78 units at the Jubilee at 235 Main St. were also lost to renovation.

The Carnegie report doesn’t include the cost of rent at hotels owned and operated by the provincial and city governments. Swanson said that’s because many of the hotels rent at the welfare shelter rate of $375 a month or one-third of a tenant’s income.

Though the provincial government has committed to fund more housing projects in the Downtown Eastside, and the federal government unveiled a national housing strategy, Swanson noted the group’s research found only 21 units of new housing at the welfare rate opened last year.

She acknowledged the provincial government promised in January to spend $83 million on four housing projects in the Downtown Eastside, including $30 million on a 231-unit building at 58 West Hastings St. But, Swanson said, those projects won’t likely be built for three to seven years.

The project at 58 West Hastings is the same one that Mayor Gregor Robertson signed a pledge to have all units rented at welfare and pension rates of $375 per month. So far, the funding commitments allow for the project to proceed with 50 per cent of the units to be rented at $375 per month, and the other half at 30 per cent of a household's income level, but not to exceed $1,272 per month.

The Carnegie group’s report was released the same week the city is conducting a homeless count. Last year, volunteers counted 2,138 people as homeless, with more than 500 living on the streets and the balance staying in some form of shelter.

The Carnegie report estimated that one in 18 people in the Downtown Eastside are homeless, and Swanson expects this week’s count to show an increase in the number of people without a home. If the count shows a decrease, Swanson suspects the reason will be connected to the hundreds of people in Vancouver who died of a drug overdose over the last couple of years.

The hotels are often seen as temporary residences for people, with some eventually finding permanent homes and others ending up on the street. In October 2013, Dr. William Honer spoke to city council about research that he and his colleagues conducted on 293 tenants living in hotels.

Honer, the head of the University of B.C.’s department of psychiatry and scientific director of the B.C. Mental Health and Addictions Research Institute, found that almost three-quarters of the tenants were mentally ill and nearly half had a neurological disorder such as a head injury or stroke.

Almost all had problems with addiction, he said, noting the most prevalent drugs were stimulants such as cocaine and amphetamines. Nearly half of the participants were psychotic, which Honer described as one of the most severe conditions of psychiatry, where people lose connection to reality.

The Carnegie group made several recommendations in its report, including having governments buy or lease hotels, designate enough land in the Downtown Eastside to build 5,000 units of social housing, raise welfare rates and make significant investments in housing.