"Milltown to metropolis”.

Thirty years later, that’s how Howard Meakin sums up Expo 86’s effect on Vancouver. Since 1999, Meakin has been the proud owner of Expo’s legendary McBarge, the floating McDonald’s that served up to 1,400 people in one sitting. Meakin is busy cleaning up and renovating the McBarge at a secret location in Maple Ridge, hoping to open it back up to the public in some capacity this year to coincide with the 30th anniversary of Vancouver’s “World Exposition on Transportation and Communication”.

A TURNING POINT

Depending on whom you ask, Expo 86 was either the best or worst event that ever occurred in this city. What most people can agree on, though, is that Expo was indeed Vancouver’s turning point. As concert promoter Bud Luxford once infamously told the Vancouver Sun, “We invited the world and they didn’t go home”.

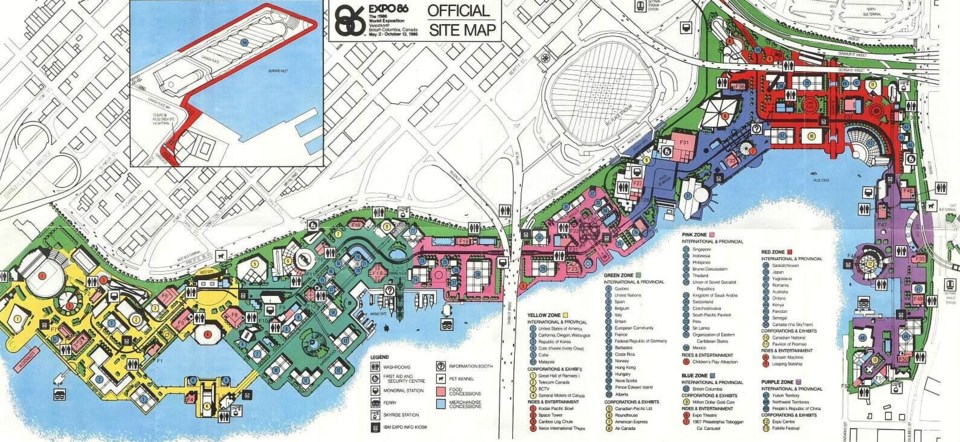

For those who attended, worked, or volunteered at the fair between May 2 and Oct. 13, 1986, the memories live on three decades later. “I can say without a doubt that Expo 86 was one of the greatest times in my life,” says Tod Maffin, a popular local public speaker, broadcaster, and marketing expert. “I was 16 in the summer of 1986, so for me Expo represented a coming of age. I had my first kiss under one of the rides in the Yellow Zone, and over the course of the summer I worked at arguably the three busiest restaurants on the whole site: McBarge, the Unicorn Pub, and the Saskatchewan Pavilion Restaurant. That Saskatchewan restaurant was a surprise hit, mostly because of their massive lemon meringue pies. Remember the line ups?”

Maffin was also part of the service team to hold an Expo record at the famous floating McDonald’s. “McBarge was so packed all the time that serving customers turned into a kind of performance art, like the bartenders in Cocktail but with fast food. The crowds loved it. Our crew held the summer record for selling something like 800 soft-serve cones in a hour”.

Lisa Christiansen is currently an on-air personality for CBC Radio One, but in 1986 she was fresh out of journalism school and working as a reporter for none other than the Westender. She had a press pass for Expo and went often. “There was always something going on at Expo, and having fireworks every night for six months was surreal”, remembers Christiansen. “My friends and I would barbecue on the roof tops of our West End apartments with the fireworks in the background. That’s probably my favourite memory, but I also remember too well the evictions to make room for tourists. I think that is one the worst things to happen in our city’s history.”

EVICTION FRICTION

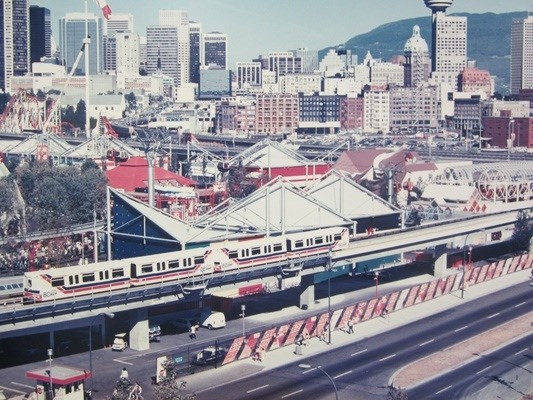

Prior to Expo’s takeover of a massive swath of waterfront real estate on the north side of False Creek, which stretched from the Granville Street bridge all the way ‘round to what is now Olympic Village, the site was primarily filled with industry: CPR rail yards, aging factories, and warehouses. With the exception of the restoration of the Roundhouse at the foot of Davie (saved because of Expo’s transportation theme), the rest was bulldozed. Also removed were the upwards of 600 long-term residents in neighbouring Downtown Eastside hotels, in an effort to create space for the incoming tourist invasion. Some evicted residents had lived in the single-room-occupancy hotels for decades.

Joe Keithley, lead singer of D.O.A., was particularly moved by the story of Olaf Solheim, an 85-year-old retired logger who was forcibly evicted when the landlord removed the door from his room. After wandering the streets, Solheim died destitute in April 1986.

D.O.A. released a 1986 EP entitled Expo Hurts Everyone, and played a benefit concert for the evictees at Malkin Bowl in Stanley Park alongside folk-protest legends Pete Seeger and Arlo Guthrie (who were both ironically also playing Expo). The gig raised $10,000 for the displaced. True to their word, Keithley and the members of D.O.A. never once set foot on the Expo grounds.

Despite D.O.A.’s boycott, live music was omnipresent throughout the continuous, party-like atmosphere of the fair. In one of the most notorious incidents of the entire six-month Expo run (and one of the most infamous moments in Vancouver music history), local punk rock band Slow kicked off what was to be a live music series called the “Festival of Independent Recording Artists”. The gig was on BC Day, Aug. 4, 1986. Bassist Stephen Hamm, now of the Evaporators, remembers the chaotic night clearly.

“Expo was incredibly unpopular in the eyes of the majority of the alternative music community and we were under a lot of pressure, perhaps self-imposed, to do something to protest a lot of really lousy things that happened, like the evictions,” recalls Hamm. “Slow prided itself on being a volatile, unpredictable and dangerous rock ‘n’ roll band – probably the only one this town has ever produced”.

Because of the promise of a large guarantee and the chance at making a statement on the Expo grounds, Slow took the gig.

“They scheduled us to play the same day Expo was paying tribute to outgoing Social Credit Premier Bill Bennett, who was at the helm of what we thought was a lot of the injustice,” says Hamm. “It gave our singer Tom Anselmi the opportunity to open the set by encouraging the audience to join him in a ‘Sieg Heil Bill Bennett’ chant, which didn’t go over well with Expo officials.” Within minutes, organizers shut off power to the stage, which triggered various members of Slow to drop their pants, semi-exposing themselves in an act of further protest. The situation devolved from there.

“The kids in the audience decided to riot,” states Hamm. Chanting “Expo injustice”, fans marched on the BCTV Pavilion, which aired live, nightly newscasts from the Expo site. The rioters caused the news to be cancelled mid-broadcast. “In desperation,” Hamm recalls, with a chuckle, “they cut straight to that night’s late movie, which just happened to be Rock ‘n’ Roll High School featuring the Ramones! You can’t make this stuff up!”

Media personality Terry David Mulligan, now with Roundhouse Radio, was interviewed the next day for BCTV about the incident. “Why this band was booked is beyond me. They’ve never proven themselves to have any redeeming social value or responsibility whatsoever.” The rest of the Festival of Independent Recording Artists was promptly cancelled.

Expo 86 has sustained a long echo in indie music, however. Bellingham band Death Cab For Cutie have a song called “Expo 86”, and Montreal indie rock band Wolf Parade (whose members are mostly from BC) named an album Expo 86. Vancouver pop favourites Said The Whale sing about Expo in their sea-shanty protest song “False Creek Change”, accusing that Expo “exploited her shores”. Songwriter Ben Worcester was only two years old in ‘86, but grew up across from the Expo site left vacant for years. His parents still live in Charleson Park, their False Creek co-op home for over 40 years. Their view has eventually gone from mountains to towers of glass.

CULTURAL CATALYST

Ron Woodall was the creative director for Expo 86, and the man responsible for the look, feel, content, and personality of the fair. It was Woodall who morphed Expo 86 from the educational, exhibit-heavy expositions of its predecessors, into what many considered an environment of celebration, colour and sound. In the end, it worked. Despite the protests and displacement, Expo 86 was a massive success, attracting over 22 million people, and putting our city on the worldwide map forevermore; but even Woodall is uneasy of Expo’s legacy.

“When Expo ended, there were two points of view,” Woodall recollects. “One was to salvage as much as we could, to become a permanent legacy park, mid-city. The other was to totally demolish it and market the area to developers. When I see the Hong Kong-like outcome,” says Woodall, referring to the wall of steel and glass towers that have sprouted from the Expo site, “I wonder if the Expo site should be regarded as Ground Zero for the new Vancouver we are experiencing today”. Kerry Gold, real estate columnist for the Globe and Mail, concurs. She was a rebellious teenager in 1986 and refused to attend, and doesn’t pull any punches when it comes to Expo and its aftermath.

“I see Expo as one of our neediest, most insecure moments as a city. Economically, we were in dire straits, and Expo was when we asked the world to bail us out. We specifically turned to Asia for an injection of global money that turned out to be our first fix,” says Gold. “I think we all see the price we’re paying, not just in terms of Vancouver’s unaffordability, but as a community, too. I think the fact that nobody has even planned an official Expo celebration tells you how bad a taste it might have left.”

Tod Maffin, who still has his Expo 86 volunteer card, doesn’t see it that way. “Expo’s positive legacy far outweighs the bad,” he asserts. Alongside Vancouver’s permanent, Expo-built landmarks like BC Place, the Roundhouse Community Centre, and the Sun Yat-Sen Garden, Maffin cites Canada Place, Science World, and the Skytrain as integral components to Vancouver’s cultural and civic development. “Look at TED [moving to] Vancouver,” he suggests, as a recent result. “The growth was always going to happen, Expo just put us on the radar.”