It’s January, 1914 and the Karluk has been caught in sea ice, drifting off the Siberian since the previous August. The wooden-hulled ship is a former whaler, called into service by the Canadian government for its first major scientific research study in the Arctic.

It’s dark, as in 24 hours of no daylight. The wind is howling, the snow is blowing and in the midst of the bleakness, there’s a horrendous noise. A chunk of ice has pierced the hull. Water starts gushing in.

Captain Bob Bartlett had never been confident of the boat’s worthiness under such harsh conditions and weeks earlier, he had ordered the crew to build igloos on the ice and start unloading provisions for their five-year voyage. As the frigid Arctic water continues to flow into the hull, it soon becomes obvious that they are indeed abandoning ship. Cpt Bartlett is last on the ship, playing Chopin’s Funeral March on his Victrola before he finally steps off the boat joins the others on the ice. They stand and watch as the sea swallowed the boat whole, its mast breaking off with a crack before disappearing.

They set up Shipwreck Camp and start preparing for their survival. In the days before GPS and Coast Guard rescues, Barlett knows he can’t wait for them to be rescued but he doesn’t want to start the trek to Wrangel Island of the coast of Siberia, 100 miles to the south. until there is a hint of daylight. Four of his crew disagree and set off, never to be heard from again. (Four more died while setting up caches on the way to Wrangel Island.)

On February 19, 1915, Bartlett decides it is time to leave the makeshift camp. Travelling by three dog sledges pulled by 12 dogs, the remaining group of 17 sets off for the uninhabited Wrangel Island. They arrive on March 12.

After six days of rest, Bartlett and an Inuit guide, Kataktovick, set off, crossing the ice to Siberia, stopping in small villages along the way until they finally arrive at the Bering Strait where they must wait for a ship to take them to Alaska. Seven hundred miles from Wrangel, they arrive at St. Michael, Alaska. The first thing Bartlett does is wire the federal government about the need to get a ship to set off to rescue the survivors on Wrangel Island. He’s on his way when another ship anchors off the island and welcomes the survivors — three have died — on board. The survivors share their stories — digging for roots and hunting ducks, seals and walrus — with Bartlett when he joins them the next day.

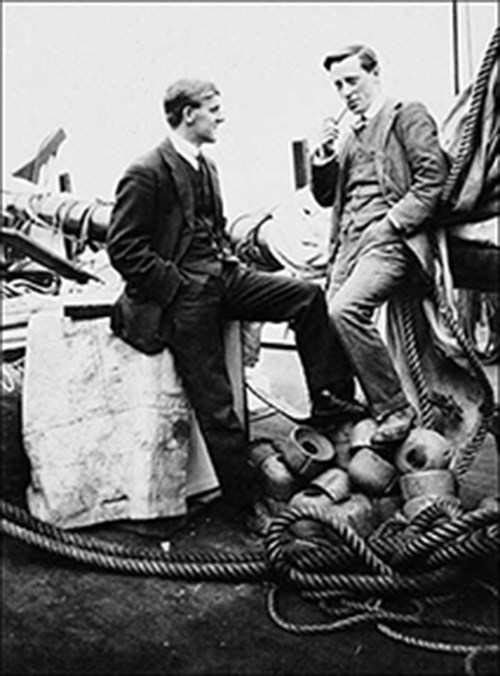

Meanwhile, back when the Karluk had first become trapped in ice, the leader of the northern expedition, Vilhjalmur Stefansson, decided to leave the ship with five other men, 14 dogs, and two sledges to hunt caribou. One of those men was Diamond Jenness, known for being a crack shot with his Ross rifle. The plan was to return in 10 days but two days into their hunting foray, winds blew the Karluk west. There was no way the two groups could be reunited so Stefansson and his group set off for Alaska by dog sledge, staying with Inuit families whenever possible.

Jenness — whose jeweler father named his sisters Ruby and Pearl — was an ethnologist who studied classic Latin and Greek in university before accepting the Canadian government’s offer of $500 a year to join the Arctic expedition. Packing pocket versions of Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey, he set off on the Karluck eager to learn more about the “people of the twilight.” Eventually, he’d author five of the 13 volumes of research material from the expedition, which helped establish Canada’s sovereignty in the north.

His grandson is Dr. John Jenness, who teaches at BCIT’s School of Energy. Dr. Jenness was at the Vancouver Maritime Museum on March 27 when Parks Canada unveiled a new plaque to commemorate the Karluk and its crew.

Back in 1925, the federal government had another plaque made in Ottawa, listing the names of those who died during the expedition. This second plaque, which highlights the expedition’s important contributions to our knowledge of the north and its people, will have a permanent home in Esquimault.

“It’s our own northern version of Ernest Shackleton’s remarkable expedition [to the Antarctic],” Cpt. Ken Burton said on behalf of the Maritime Museum.