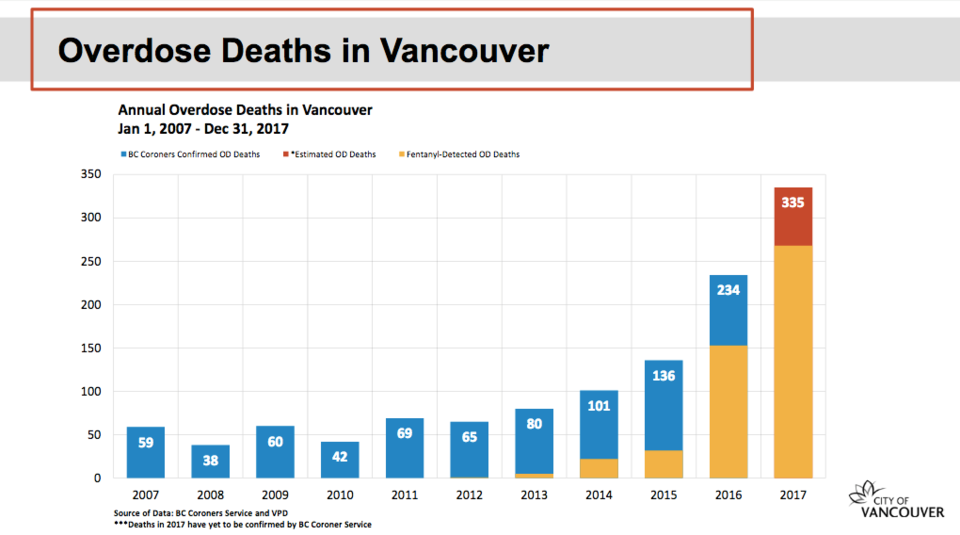

A total of 335 people are suspected of dying of a drug overdose in Vancouver last year, with more than 250 connected to the deadly synthetic narcotic fentanyl.

Mary Clare Zak, the city's social policy director, told city council Wednesday in a presentation that the number of deaths is unprecedented in Vancouver when compared to previous years.

"It's an absolute historical high, we've never experienced this," she said, noting staff collected the year-end data from the Vancouver Police Department and has yet to be confirmed by the BC Coroners Service. "We expect that report from the coroners office shortly."

Statistics show 234 people died in Vancouver of an overdose in 2016, which surpassed the 136 lost in 2015 and 101 in 2014. The lowest number of overdose deaths recorded in Vancouver over the past decade was in 2008, with 38 deaths.

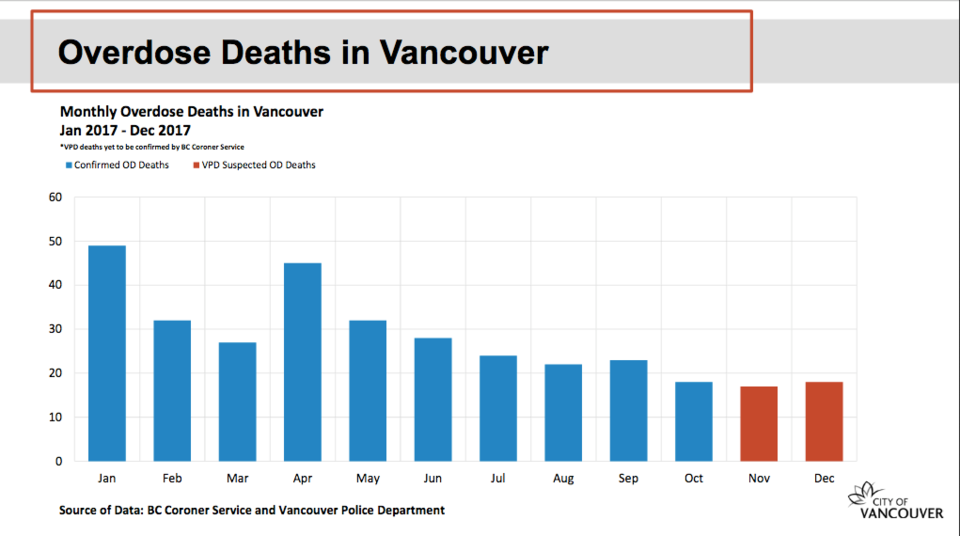

In showing bar graphs of the statistics, Zak suggested there is "perhaps some better news on the horizon," with a slight decrease in overdose deaths recorded in November and December when compared to the first 10 months of 2017.

"What we're seeing here is a trend that the number of deaths per month are actually on a downward trend," she said. "However, we know we have to remain diligent, we need to remain attentive."

The city is also seeing the ratio of deaths to calls responded to by firefighters widen, with one death for every 29 calls in the Downtown Eastside, the epicentre of the crisis in Vancouver.

The ratio on the west side of the city was one death for every 23 calls. The northeast section was one for every 17, yet ratios in midtown (one death for every 10 calls) and south Vancouver (one for every nine calls) continue to be a concern for health officials.

Firefighters responded to 6,234 overdose calls last year and administered naloxone 215 times. In 2016, firefighters answered 4,709 calls and administered naloxone 141 times.

"So we know that it's really quite possible that the interventions, which are mostly in the Downtown Eastside, are really having an effect," Zak said.

Those interventions include new treatment clinics, prescription heroin programs, adding an additional medic unit for firefighters, opening "overdose prevention sites," the widespread use of the overdose-reversing drug naloxone, more testing of drugs and drug education forums at community facilities.

In December, the provincial government announced the opening of an "overdose emergency response centre" to better collect data on deaths, identify trends and work with new health and community teams across the province to rapidly respond to the crisis.

Dr. Patricia Daly, who is Vancouver Coastal Health's chief medical health officer and oversees the response centre, said in her presentation to council the centre is "meant to build on the good work done to date."

But, she said, a big focus of the centre is to intervene earlier with drug users. Daly noted analysis done by the health authority over the last year of some of the deaths showed 80 per cent of people who died had visited a hospital emergency department in the year prior to death.

"So there's an opportunity to identify people who are at risk of overdose death and intervene earlier," she said. "That's what we need to be doing. It can't just be about giving naloxone and treating overdoses when they happen."

Vision Coun. Andrea Reimer asked Daly and Dr. Mark Tyndall, the director of the UBC Centre for Disease Control, whether the number of deaths had decreased because of interventions, or whether the death toll dropped because the population of chronic drug users had "just died off."

Tyndall and Daly both said health officials do not know exactly how many people are opioid addicts in the province, noting an example of a construction worker who died of an overdose.

"There's so many young men in construction — this kind of population — who had a steady supply of diverted pharmaceutical opioids for a long time," Tyndall said. "All of sudden, one morning it's: 'I don't have them anymore and what am I going to do?'"

Added Tyndall: "Many people who we really wouldn't associate as targets for our harm reduction are being found dead, and it's really because they've just run out of clean options."

@Howellings