Bike routes – like the recently approved 10th Avenue bike lane – bike share, bike racks and bike-friendly intersections continue popping up around Vancouver like wildflowers. It’s a boon to many cyclists who have long looked to places like Amsterdam, Copenhagen and Portland as model bike-friendly communities. And it’s a source of concern for some residents who wonder about the impact all these changes are having on automobile parking and traffic.

“I try to avoid it [downtown Vancouver] like the plague” because of snarled traffic, particularly near the new Nelson and Smithe street bike infrastructure, says Fairview resident Rob DuMont, 40, who supports promoting cycling in the city (he also cycles) but not at the expense of motorists.

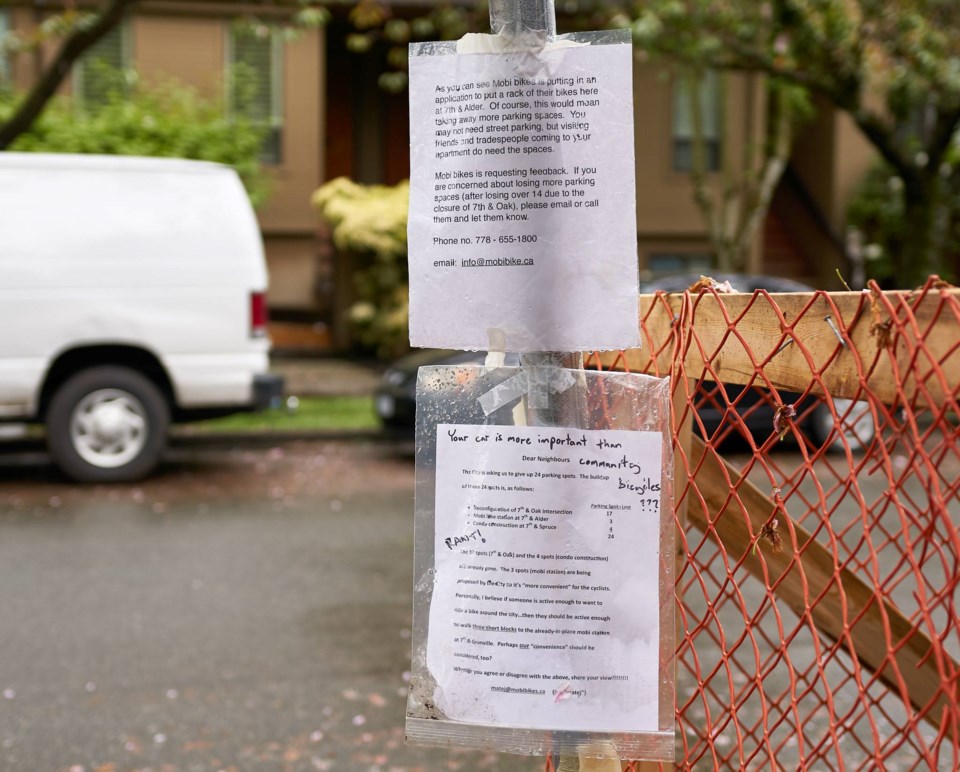

DuMont’s normal commute to work was recently cut off by the construction of two cul-de-sacs along the 7th Avenue bikeway that borders Oak Street, and he’s concerned that money spent on bike infrastructure is only adding to traffic congestion in his neighbourhood and downtown. Three parking spaces at the front of his building were recently removed to install a new Mobi bike share station, something that also came as a complete surprise to DuMont who says he received no notification by mail or email about the impending changes to road infrastructure near his home.

DuMont says he feels like Vancouver City Council is using the growth of the city’s population and number of commuters as an excuse “to take out vehicle lanes, make it more difficult for cars,” in the interest of bikes.

Shifting gears

Walking, biking or taking public transit represented around half of commuter trips in Vancouver; and, the new goal set by the city’s Transportation 2040 report would see that figure increase to two thirds. Part of achieving that target is to make cycling more comfortable for all ages and abilities, says Paul Storer, manager of transportation and design with the City of Vancouver (CoV), and increasing the number of end-of-trip facilities, such as secure bike parking.

The City’s 2017 budget allocates more than 40 per cent of its new transportation infrastructure spending towards walking, cycling and transit, making this “a big year for transportation investment,” according to Storer. And he understands that these changes, including earmarked upgrades to the Granville and Cambie bridges, are raising concerns.

“Our goal is to continue to better manage congestion throughout the city because it really is important to us to keep our arterial network working really well,” says Storer.

“We’re not trying to lower the number of motor vehicles on the road,” he adds. “Our 2040 plan is clear that we might, in 2040, see a small reduction in the number of motor vehicles on the street, but, for the most part, where we’re reallocating space is where we can do that without having big impacts on the arterial network.”

That said, he admits “it’s a challenge in places.”

For bigger projects, Storer says the city provides many opportunities for the public to get involved in the consultation process, but realizes that, “every once and a while we hear from someone that hadn’t heard about it, and we’re trying as much as possible not to make that happen. […] Our goal is to talk to everyone who might have an opinion on the matter.”

BIAs weigh in

West End BIA executive director Stephen Regan has some concerns about being included in decision-making processes regarding new bike infrastructure in the West End.

“Business and BIAs like to be part of the discussions,” he says, adding that the West End BIA hasn’t taken a hard line on bike lanes and bike share either way, but notes that the needs of all road and sidewalk users should be considered when putting in new infrastructure, as it can impact other uses, such as patio space for businesses.

On the other hand, the Downtown Vancouver BIA has become a proponent of bike infrastructure, such as bike parking spaces. President and CEO Charles Gauthier notes that several building owners are seeing cycling infrastructure, including the Mobi bike share stations, as a value-added.

Having the option to take multiple modes of transportation, Gauthier opines, “enhances the desirability of downtown as a place to live, work and do business… it makes us much more competitive and provides us with an advantage that other employment centres don’t necessarily have.”

Making way for accessibility

Erin O’Melinn, the executive director of HUB Cycling, a cycling advocacy group, endorses the Mobi bike share system for a few reasons. Currently in her third trimester of pregnancy, O’Melinn uses the bikes because their step-through design is much easier to manage with her belly than her personal commuter bike. She also appreciates how it fits into the city’s vision to make cycling more comfortable for all ages and abilities.

“Cycling is a really helpful way to move more people with less space and cost,” she states. Separated bike lanes and intersections designed with cyclists in mind improve safety and increase the number of cyclists, particularly children and those who may have concerns about riding near parked cars and traffic.

As a driver and cyclist, Caitlin Hanna, 27, supports upgrades to the cycling network so long as they don’t trump the needs of other road users. The controversy around access to Vancouver General Hospital for people with disabilities was particularly poignant for the UBC occupational therapy masters student.

“I don’t want my rights as a cyclist to overtake someone’s fundamental rights to access health care,” she says.

However, Hanna also appreciates having access to separated bike routes that keep her away from opening car doors and traffic – which can provide a safeguard against collisions.

“I don’t think I would have been riding every day to North Vancouver if I didn’t have designated bike lanes, especially through Stanley Park and across the Burrard Bridge through downtown,” admits the Kitsilano resident who commuted to the North Shore for a work placement recently. “Being [in a] protected [bike lane] there is an incredible asset.”

More...

“Cycling is the fastest growing mode of transportation in Vancouver,” according the City of Vancouver’s website. Ridership for the month of August along Vancouver’s separated bike lanes is a case in point, as outlined in the city’s Engineering Services department estimates:

• Burrard Bridge

130,000 in 2009 to 182,000 in 2016

• Dunsmuir Street

48,000 in 2010 to 69,000 in 2016

• Hornby Street

54,000 in 2011 to 75,000 2016

Pedal power

Bicycling represented 10 percent of trips to work in Vancouver in 2016, according to a 2017 update from the Director of Transportation report, compared with 6.6 per cent in 2013. In total, there were an estimated average 128,100 daily cycling trips in 2016, up from 50,000 to Vancouver destinations in 2006.