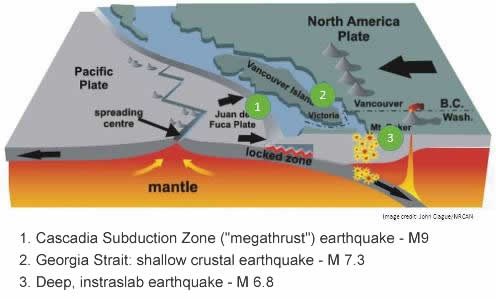

Seventy-five kilometres underneath Vancouver, a massive Pacific plate is slowly making its way eastward.

It started in the Pacific Ocean, went under Vancouver Island and the Strait of Georgia and is now underneath the North American plate that Vancouver sits on.

Its pace is slow but steady, about six or seven centimetres a year — about the same amount your fingernails will grow in a year, says John Cassidy, an earthquake seismologist with Natural Resources Canada.

Monday night’s 7.9 magnitude earthquake in the Gulf of Alaska is a reminder that we live in a very active earthquake area, Cassidy says. Earthquakes are happening all the time, and while some of them are big, they are deep under the surface.

“It’s all ongoing processes,” he said in a telephone interview Tuesday morning from his office in Sidney. We live in a region with one of the most complex earthquake systems.

Cassiday had been awake since 2:30 a.m. when finally realized his phone was ringing with calls about the tsunami alert. The alert went out at about 1:45 and included all B.C. coastal areas, the west coast of Vancouver Island and the Juan de Fuca. It did not include the inner coast and Strait of Georgia.

Vancouver Island is the city Vancouver’s buttress when it comes to potential tsunami dangers. Vancouver Island’s west coast takes the brunt of a tsunami, which is why people in Tofino spent much of the night gathered in the community hall. Most of a tsunami’s energy dissipates once it reaches Vancouver and the North Shore, where only small waves are likely to be experienced, Cassidy says.

However, that doesn’t mean we are immune from the impact of large waves following an earthquake. An earthquake could trigger a mudslide, washing tonnes of rock and gravel into the water and generating very large waves.

“With any strong shaking it’s a good idea to move away from water, especially in mountainous areas,” Cassidy says.

Earthquakes are notoriously difficult to predict, he says. “So far there is no reliable technology to predict the time, location and magnitude of an earthquake anywhere on earth. It may just be a random process.”

We are approaching the 318th anniversary of the magnitude nine Cascadia earthquake that struck Vancouver’s coast on Jan. 16, 1700. It caused a tsunami that reached Japan. The length of the rupture was almost 1,000 kilometres, with an average slip of 20 metres.

Asked about the effectiveness of Tuesday morning’s tsunami alert, Cassidy said, “from what I’ve heard it’s worked with, with community centres filled with people in the middle of the night.”