For six years now, the 220 officers working out of a small police department in a suburb of Boston, Mass. have been doing something that Vancouver police officers may one day be trained to do: use a life-saving nasal spray medication on drug overdose victims.

The Quincy Police Department was the first department in the United States to begin using the nasal spray form of naloxone, and it has seen a dramatic drop in the number of drug overdose deaths in the city of 100,000.

Officers responded to 673 overdoses since the program’s inception in October 2010 and reversed the effects of an overdose on 448 people, said Det.-Lt. Patrick Glynn, who oversees Quincy’s narcotics and special investigations units.

“The correlation between administering it as soon as we’re on scene and the success rate is very good,” said Glynn, noting the officers’ use of naloxone helped reduce the drug death rate by 66 per cent in the program’s first year. “There were a lot of people who didn’t think police officers should be carrying or administering a medication. But once they saw the value of it… well, the numbers speak for themselves.”

The department pioneered the program with the support of the Department of Public Health to combat the growing number of overdose drug deaths in Quincy. News of the program’s success quickly spread, and now several police departments across America are equipped with the medication.

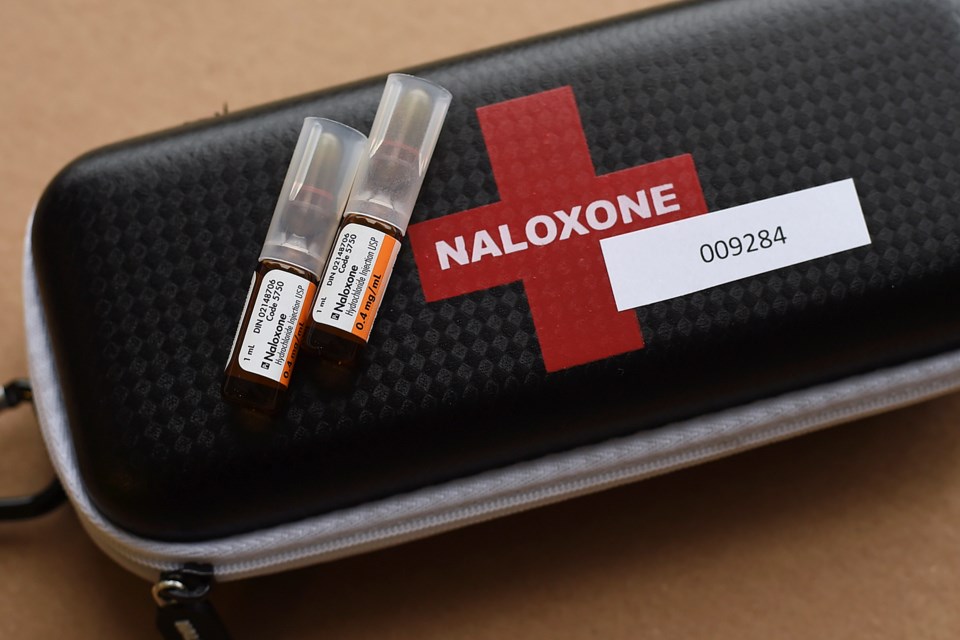

Naloxone, also referred by its brand name Narcan, quickly reverses the effects of opiods such as heroin and fentanyl on the body by restoring breathing within two to three minutes. The effects last for at least 30 minutes, giving time for emergency responders to arrive.

The medication and its use is making news in Vancouver after the provincial government announced Jan. 28 that firefighters in Vancouver and Surrey can administer naloxone with a syringe. The government also expanded the number of paramedics certified to use the medication.

That announcement came after the B.C. Coroners Service released a report in January showing 465 people died in B.C. last year of an apparent illicit drug overdose. That’s an increase of 27 per cent from the 366 people who died in 2014. The VPD announced last Friday that officers investigated 11 deaths in the past 16 days believed to be a result of a drug overdose. Typically, two to three people per week die of drug overdoses in Vancouver, according to police.

Police Chief Adam Palmer said he believes in the benefits of police using naloxone to reduce drug deaths. But, Palmer said, he will not allow his officers to administer the medication with a syringe. He prefers the nasal spray, saying it’s more “low risk” for officers.

“I don’t want the officers having to inject needles into people but we’re definitely interested in some sort of a nasal spray that they have in the American police departments,” said Palmer, noting he made his intentions known to Vancouver Coastal Health, which has offered to train officers if the spray is approved in Canada. “It makes sense.”

The problem, however, is no drug company has applied to Health Canada to have the nasal spray approved in this country, said Sean Upton, a spokesperson at Health Canada, in an email to the Courier. But Upton pointed out Health Canada has received inquiries from manufacturers interested in bringing “different formulations” of naloxone to the Canadian market.

“Some manufacturers have indicated that an application may be submitted in the near future,” he said. “In the meantime, Health Canada continues to provide advice to inquiring manufacturers in order to support future drug submissions.”

Upton said Health Canada is concerned about the growing number of opiod overdoses and deaths across the country, noting the department amended the prescription drug list in January to allow non-prescription use of naloxone for emergency use outside hospitals. The new regulation builds on the B.C. Centre for Disease Control’s “Take home naloxone” program, which trains people to administer the medication, including more than 100 members of the Vancouver Area Network of Drug Users.

Mayor Gregor Robertson, who doubles as chairperson of the Vancouver Police Board, said he supports Palmer’s push to have officers carry the nasal spray. He said he will follow up with the health authority to emphasize the need for the service.

“We want to see this happen but obviously it’s up to the health professionals to determine what’s appropriate,” Robertson said.

In an email to the Courier, Vancouver Coastal Health reiterated its support for police to use the nasal spray form of naloxone but said it is not as effective as injected naloxone.

Capt. Jonathan Gormick, spokesperson for Vancouver-Fire Rescue, said about 70 firefighters in four of the city’s fire halls will be the first to receive training on how to administer naloxone. That training should be completed by mid-February, although Gormick said the long-term goal is to have all firefighters certified on how to administer naloxone, which involves drawing the medication from a vial into a syringe.

“It’s a great step forward — it’s awesome,” said Gormick, noting the department responded to more than 2,600 calls last year where someone had gone unconscious after using drugs or alcohol, or a combination of both. “There’s been a general feeling of helplessness when firefighters show up at what’s obviously an opiate overdose and there’s not much we can do besides provide respiratory support.”

Though the Quincy Police Department is best known for equipping its officers with the nasal spray, Glynn said officers now also use an “auto-injector” to administer naloxone. He described the device as resembling and operating much like an EpiPen, which is used to treat severe allergic reactions.

“It delivers the medication and immediately retracts back in,” he said. “It’s as closest to zero problems that you could have as far as accidental sticks [with the needle], or anything else. There’s no drawing of medication. It’s actually much simpler than the nasal spray.”

Another benefit of police being equipped with naloxone — in either form — is the bonds the department has built with drug users and drug advocates normally at odds with police, Glynn said.

“Once you start reversing some of these overdoses and everyone has the mindset that they’re a person, you start to see dramatic results with the public supporting the police much more than they have in the past,” he said.

When told that Vancouver’s police chief is interested in equipping his officers with naloxone, Glynn said he would recommend the department keep pushing to have it approved for use.

“It’s going to save lives. It’s a win-win situation for everybody.”

@Howellings