Peer out Harold Steves’s third-floor window and your eyes might dwell on a sweep tidal marsh. Look further, and you’ll soon find the water’s edge — a confluence where a great mixing occurs as the Fraser River slams into the Pacific.

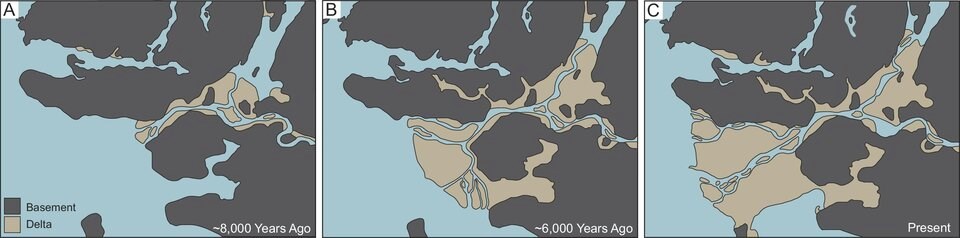

For more than 10,000 years, the final reaches of Western Canada’s largest river have whipped across Metro Vancouver like an untethered fire hose, its channels depositing vast quantities of sand, mud and silt as they shifted.

At its margins, the rising land has allowed tidal marshes to proliferate into an immense nursery for wild salmon and one of the largest stop-over sites for migrating birds in western North America. That same sand also now forms the base for several of the region’s cities.

But in recent decades, the dynamics of this geologic conveyor belt have shifted. And as the supply of sediment dwindles, the sea marshes that nurture wildlife and protect cities such as Richmond from storm surges are rapidly receding, just as sea levels rise and land sinks.

“The grasses aren’t going out like they used to,” said Steves, who formerly served as a Richmond city councillor and member of B.C.’s legislative assembly. “It used to go out almost a kilometre more.”

In the 1980s, government estimates suggest more than 17 million cubic metres of sand and mud passed through the lower Fraser River every year — equivalent to flushing the weight of 115,000 blue whales into the sea.

But for many experts, that figure is clouded in doubt. Unlike in Europe and the United States, Canadian government programs that once monitored river sediment have collapsed.

Meanwhile, the Vancouver Fraser Port Authority dredges about 3.7 million cubic metres of sand from the riverbed every year to ensure safe passage for ships.

Without a continuous monitoring program, some experts worry dwindling sand supply could lead to a critical shortage of sediment and the collapse of tidal marshes. Without those marshes, the ability to baffle storm surges and rising sea levels could balloon the costs of flood defences, said Shahin Dashtgard, professor of earth sciences at Simon Fraser University.

“It’s huge money. We're talking in the tens of billions of dollars,” said Dashtgard. “They're ignoring it.”

Farmland is 'becoming aquatic'

Metro Vancouver’s sand problem has been brewing for more than 150 years, but its roots stretch back to the end of the last ice age 10,000 years ago.

As the planet warmed and glaciers receded, the land began to rebound. The Fraser River cut through the rising and melting landscape, carrying rock ground up by glaciers and depositing it across what is now the Fraser Delta.

This process created a productive ecosystem — filled with spawning salmon, wild birds and the predators who came to feast on them — and soon became home to numerous First Nations.

“People love living on deltas. They have since the beginning of time,” Dashtgard said. “They were like the original highways.”

The Fraser River's natural processes continued largely unchanged until European settlers arrived en masse in the late 1800s. As farms and cities expanded, dikes were built to protect them from seasonal flooding. The structures also cut off cities from the sediment that originally built them, and today, the ground continues to settle under the weight of development.

Richmond resident Avtar Thandi and his neighbours are living the consequences firsthand. Just inside Richmond’s dike system at a bend in the Fraser’s North Arm, Thandi has struggled to farm on land that is chronically flooded. Over the past decade, he said much of his property has become unusable.

Behind his twice-flooded house, a line of dying cedar saplings sit submerged in water. The once productive farmland lies fallow after the multi-generational farmer says he was forced to tear out $200,000 worth of blueberries.

“What can you grow on the land? Nothing. Ducks,” said Thandi, pointing to a paddling waterfowl. “It’s becoming aquatic.”

Still, the farmer says he’s lucky after he was recently approved for a load of fill after years of waiting. Some of his neighbours are not so fortunate and remain surrounded in a near-permanent state of stagnant water. Some houses are slowly sinking into the earth.

“You gotta raise the land. You gotta keep adding to it,” said Thandi. “It keeps getting worse.”

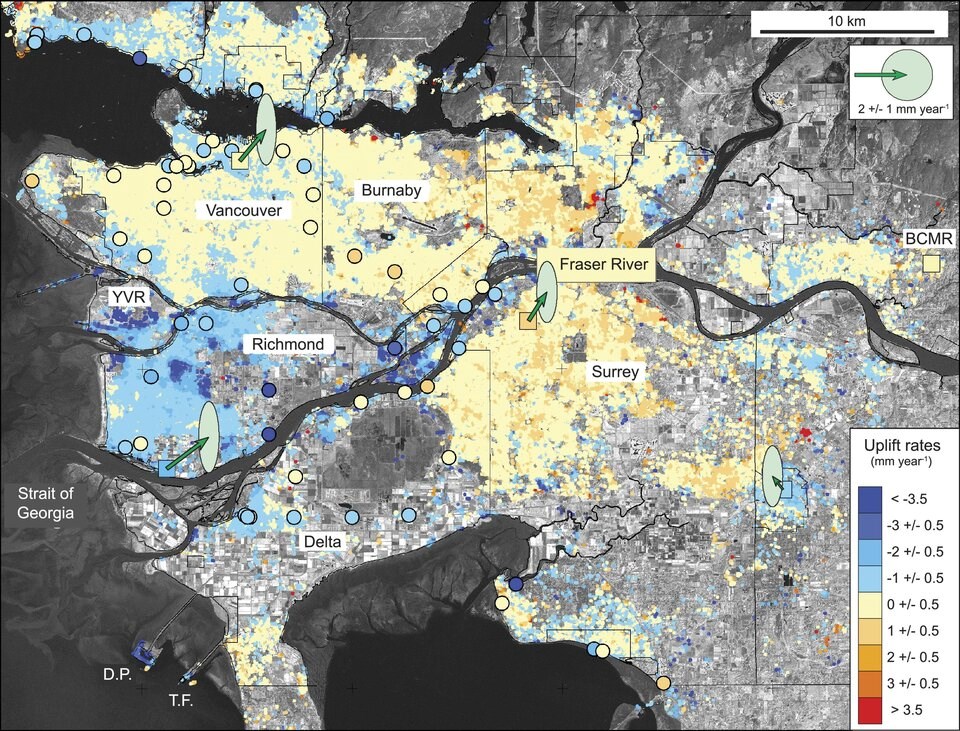

Like many other parts of Richmond, research indicates Thandi and his neighbours are sitting on land sinking at least 3.5 millimetres a year. At that rate, some parts of Richmond could drop 26 centimetres by the end of the century just as sea levels are rising.

“We’re seeing all these symptoms of a sediment supply deficit in the Fraser delta,” said Dashtgard. “It’s sinking like a large sandcastle.”

Hard flood infrastructure to cost billions

The potential costs and consequences of dwindling sediment and rising seas are enormous.

Under medium warming scenarios, climate change is expected to raise sea levels a metre higher over the next 75 years — even more should Antarctic ice sheets collapse. Retrofitting old dikes or building new ones to withstand that change is expected to cost the region billions of dollars.

Past studies have placed Vancouver among the top 20 port cities worldwide facing a triple threat from flooding, sinking land and a growing urban population. By one estimate, it could cost the region as much as US$303 billion by 2070.

Another 2012 provincial study estimated the cost of adapting to sea-level rise in Metro Vancouver to reach $9.5 billion by 2100. Whatever the final cost, it’s clear that much of the region’s 250 kilometres of dikes already require significant repairs to keep up with a changing world.

An analysis commissioned by the B.C. government in 2015 found that if record historical floods were to strike again, 71 per cent of the region’s dikes would fail.

“Almost all of the dikes are sub-standard and most will not withstand the provincially adopted design flood events,” it concluded.

That has people like Steves concerned. Tucked along the inside of a massive dike system in Richmond, his home sits on land passed down through the family since some of the earliest European settlers came to the area.

Farmers like the Steves once held nearly 800 acres on Richmond’s coastline. But the dikes bisected the land between Steveston and Terra Nova, and most farmers eventually sold their remaining holdings to government. Today, Steves and his grazing cattle are the only ones left with a private piece of tidal marsh.

“As far as our land is concerned, as the sea level rises, we’ll probably lose our field,” he said.

Hopefully, he added, “we won’t lose Richmond.”

Industry, climate change impacting Fraser's sediment supply

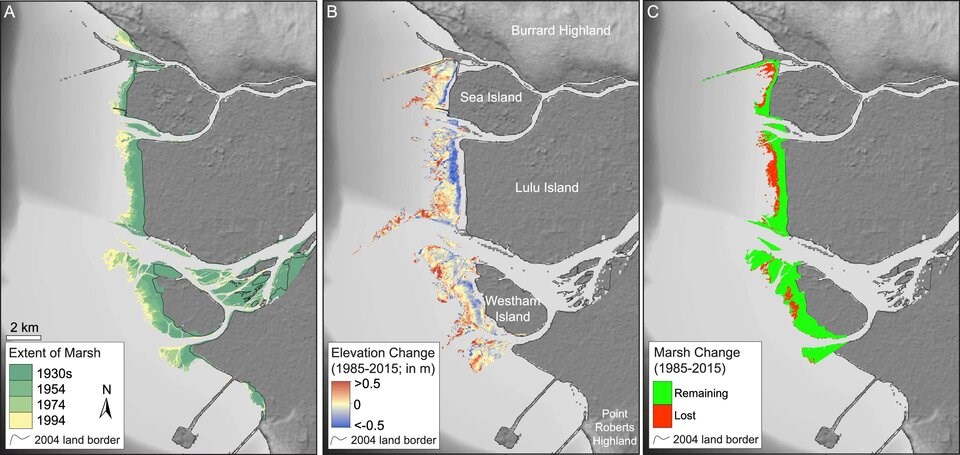

For generations, a steady supply of river sediment meant there was enough mud, silt and sand for plants to sink their stems into the tidal flats. As the marshes grew, so too did their ability to create habitat for a vast array of wildlife — a living first line of defence that slowed the force of the sea during the worst storms.

By the 1980s, Fraser tidal marshes covered an estimated 453 hectares, their maximum recorded extent since dikes were built. Since then, a combined 260 hectares of marshes have disappeared off the shores Richmond, Delta and the Vancouver International Airport, according to Ducks Unlimited Canada.

Jeremy Venditti, a professor of geomorphology at SFU’s School of Environmental Science, said part of that change was the result of shifting industrial practices.

Beginning in the 1800s, gold mining and industrial logging triggered pulses of sediment to pour into the Fraser River. By the 1990s, sediment supply began to drop after mining practices changed and the province passed a law requiring buffer zones between logging operations and rivers, studies have found.

Climate change has only compounded the situation. As B.C.’s Interior gets drier, it leaves less water to erode and move sediment into rivers, said Venditti.

“It’s basically drying up the sediment supply,” he said.

The Water Survey of Canada ran a monitoring program from 1966 to 1986. Before it ended in a wave of cost-cutting, the program found that about 17 million cubic metres of sediment passed through the Fraser annually, much it suspended in the water and shot into the ocean in a plume so big it can be seen from space.

About 25 years later, Venditti installed a sediment monitoring station in Mission, as part of an acoustic monitoring experiment.

Between 2010 and 2014, Venditti and his colleagues proved they could bounce pulses of sound off suspended sediment to get sonar-like readings.

But when they compared their results to historical measurements, they found coarse sediment supply had dropped by 50 per cent.

“It’s a lot,” he said. “It's that sediment that we're most concerned about in terms of the stability of Delta channels.”

It’s also some of the same sand the port dredges every year.

Every year, the province usually receives about 10 applications to dredge the Fraser River, according to a spokesperson for the B.C. Ministry of Water, Land and Resource Stewardship.

The biggest dredging operations are carried out under federal law at the behest of the port authority. Port spokesperson Alex Munro said the program is meant to minimize dredging, so at high tide, a ship with an 11.5-metre draft can navigate the 36-kilometre channel up to the Surrey Fraser docks.

Every year, the port identifies areas that need attention with hydrographic surveys. An estimated 3.7 million cubic metres of sand are dredged every year, said Munro.

But just how much is left over to build the Fraser delta remains a blind spot.

Venditti said he turned his monitoring station over to the federal government with the expectation they would run it. But not long after the COVID-19 pandemic hit, the station was removed, he said.

In an email, Transport Canada spokesperson Flavio Nienow told BIV the ministry does not track the total amount of sediment that passes through the mouth of the Fraser River and is not aware of any formal process in place.

Venditti says surveys show dredging has already dropped the lower Fraser’s channel by three metres in the past 50 years. He projects human activity will deepen the channel by eight metres over the next 25 years, a “huge change” that could lead to a massive amount of erosion along the river’s edge.

“It feels like we’ve been perpetuating the status quo for decades and decades and this is the result,” said Eric Balke, a senior restoration biologist with Ducks Unlimited Canada.

Marsh re-building doomed absent monitoring program

Balke is part of a pilot program testing a solution to disappearing marshes. Using sediment dredged from the Fraser River, the group has been spraying mud and sand onto the flats at Sturgeon Bank using what’s known as a mud motor.

By next fall, they hope to have added nearly 21,000 cubic metres of sediment to the area, something Balke says is a “drop in the bucket” compared to the millions of cubic metres dredged from the river and dumped at sea every year.

The idea is to demonstrate proof of concept and show marshes can be rebuilt by treating sediment as a life-giving substance rather than a waste product.

“They’re protecting our dikes,” said Balke.

Any hope of scaling the project will likely be contingent on whether someone sets up a continuous monitoring station to better understand the scope of the sediment problem, Balke said.

“I see no coordination,” he said. “I don’t want to be dramatic, but we stand to lose a lot of these ecosystems if they cannot keep pace with sea-level rise.”

The Vancouver Fraser Port Authority says it's working to minimize the impact of dredging. But Steves said he worries there’s not enough checks on the port’s power.

“This is not going to work. They’re setting the rules for themselves,” he said. “We don’t know what the Port of Vancouver is doing.”

From Venditti's point of view, the region will be left to choose between competing interests: On one side, how to safeguard an estimated $100 billion of goods forecast to pass through Canada’s largest port in the coming years; on the other, shielding millions of residents from rising seas and an eroding delta is at stake.

Governments and industry could harden the mouth of the Fraser River with expensive concrete and rip rap engineering projects, said Venditti.

Isolated pockets of erosion would be easy enough for engineers to fix, he said. But over time, the accumulation of those projects — and their maintenance — would take a toll on the natural state of the river and government spending.

“How many billion-dollar projects do you want to build?” said Venditti. “The natural beauty is going to be lost in the process.”

A second choice would be to find a balance that preserves enough of the delta’s environment so it can act as a natural defence against floods, while maintaining a safe passage for shipping. From a purely economic standpoint, that’s a cheaper way forward, said the geomorphologist.

“We have to start asking the question: What kind of Fraser delta do we really want? And then give people the opportunity to answer,” Venditti said.

But first, he said, someone needs to step up and measure the scope of the problem.