Canada’s Competition Bureau has a mandate to act as a watchdog over monopolies and ensure truth in advertising. But as the world moves to transition its economy toward net-zero emissions, a rise in false and misleading advertising has some saying the independent law enforcement agency needs more powers to combat a “scourge of greenwashing.”

On Tuesday, several environmental and health groups across the country called on the federal government to modernize the Competition Act so the bureau can better challenge companies falsely claiming green credentials.

“It’s not the sole answer to the climate crisis but it’s an important lever we should use,” said Matt Hulse, a lawyer with the environmental law firm Ecojustice.

“Otherwise, our government and public are going to be hoodwinked by these corporations.”

In November 2022, the Ministry of Innovation, Science and Industry launched a review of the Competition Act, and last week, it closed the consultation phase of that process.

Ecojustice was among more than a dozen groups that have recently submitted recommendations to the ministry on how it could reform the Competition Act to better target deceptive marketing practices around sustainability.

In a March 31 submission, Ecojustice called on the government to, among other measures, amend the act to strengthen Canada's deceptive marketing regime and address “systematic greenwashing.”

And in a 77-page submission made last month, the University of Victoria’s Environmental Law Centre called on Canada to change the Competition Act so that it requires companies to substantiate their claims over climate change.

The submission also recommended the ministry create a criminal conspiracy offence for companies collaborating to intentionally deceive the public over climate change, and ramp up “drastically higher penalties for climate deception.”

A spokesperson could not provide a timeline on how long it would take to incorporate any proposed amendments into the act.

“We are assessing the key themes raised by respondents, including the issue of greenwashing,” said the ministry spokesperson in an email to Glacier Media.

A rise in greenwashing complaints

The call comes amid a rise in greenwashing complaints to the Competition Bureau. Allegations of false and misleading advertising have been levelled at some of Canada’s largest banks, oil and gas companies, and the country’s largest forest sustainability scheme. But the bureau has made few decisions against companies.

Last year, the Competition Bureau cited a global study that warned 40 per cent of environmental claims made online could be misleading. And according to one recent survey, nearly seven in 10 Canadians don’t trust the sustainability claims companies make about their products and services.

Calvin Sandborn, senior counsel at the Environmental Law Centre, says in the 15 years between 2006 and 2021, no environmental cases brought to the Competition Bureau have been prosecuted.

Researchers at the Environmental Law Centre found that over that period, the bureau entered into 14 consent agreements with companies in cases connected to environmental claims, according to its own submission to the ministry.

Ten of those cases involved claims of energy savings for hot tubs. Other cases involved the car company Volkswagen, and only came about after the U.S. made similar decisions around the company’s misleading claims over vehicle fuel efficiency.

One of the most recent successful complaints involving green claims came from the group of Victoria-based lawyers and law students. In a 2021 decision, the bureau found the coffee-pod maker Keurig made false and misleading claims about the ability to recycle its products. Sandborn said it took over two years for the bureau to render a decision.

“The delay in these decisions is one indication that the competition regime is not capable of facing this systemic problem,” said Hulse.

“This is a whack-a-mole solution to a systemic problem. It relies on people to submit complaints one by one.”

According to many sources, greenwashing is a growing global problem. Hulse points to a recent study from the European Commission that found 53 per cent of claims about products “provide vague, misleading or unfounded information on products’ environmental characteristics.”

Last month, another study from Australia’s competition watchdog scanned the claims of 247 businesses across multiple sectors, ultimately finding 57 per cent of cases made concerning claims that were often vague, unqualified, or didn’t come with enough evidence back them up.

Even people inside companies are concerned. In North America, a 2022 survey conducted on behalf of the Google Cloud by The Harris Poll found 72 per cent of executives agreed that “green hypocrisy exists” and that their organization “has overstated their sustainability efforts.”

In the same way the U.K. and Australia have taken action, Hulse says an emboldened Competition Bureau in Canada could carry out similar market studies and dedicate expert teams to wade through the often complicated science surrounding the environment and climate change.

“We lack a strong specific piece of legislation and we lack the expertise,” said Hulse.

Competition Bureau knows it has a problem

In September 2022, the anti-trust regulator invited nearly 400 people from 40 countries to Ottawa to attend a summit designed to respond to a rising number of greenwashing cases.

“Competition agencies must stay on top of greenwashing,” noted the bureau in a summary of their findings released in January.

“False and misleading environmental claims prevent competition between businesses on their merits. They also erode consumers’ confidence in a greener economy.”

In its own submission to Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada, the bureau released 50 interventions designed to modernize competition policy in Canada. Among the recommendations, the bureau argued for greater flexibility in combating deceptive marketing tactics.

In one example, the bureau considers a case where a customer buys what’s advertised as a high-efficiency air conditioner, only to learn it’s the lowest efficiency model on the market, and holds no third-party certification. In the end, the consumer’s electricity bills are actually higher than they were before.

Currently, the bureau says it can offer some restitution, but courts still don’t have the ability to cancel contracts where there has been “deceptive marketing.”

According to a spokesperson from the ministry, the Competition Bureau “did not raise concerns about the inability of the law to target greenwashing.”

But Husle says there are clear limits under current laws. False or misleading advertising is only deemed prohibited if it’s so important to a consumer that it would change their decision to buy a product or service, said Hulse.

“Green claims do change people's shopping behaviour,” he said.. “Studies show it does matter. Let’s just take that at face value and go with it.”

Politicians a target for false advertising

In other cases, advertising is not necessarily directed at a customer. Sometimes a company might apply sustainability claims to their ethos as a whole, its value statement or reputation.

“Sometimes that claim is directed at the bigger picture of a social licence,” said the lawyer.

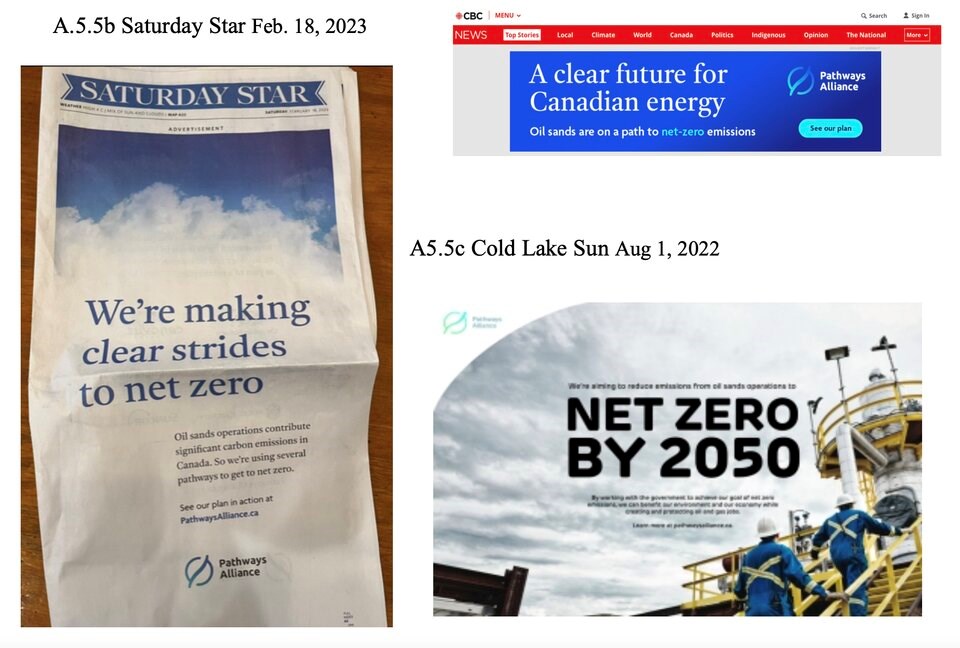

In a complaint filed last month, Greenpeace alleged the Pathways Alliance — a coalition of the country’s six largest oil sands producers — misled Canadians in several advertisements representing its plan to achieve net-zero emissions by 2050.

According to the complaint to the bureau, the six oil and gas companies ran television ads during the FIFA World Cup, the Australian Open and the 2023 Super Bowl. The ads ran across television, major Canadian newspapers, their website, podcasts, social media and at least one billboard in Vancouver, B.C.

The complaint said the advertising campaign fails to include Scope 3 emissions — those produced when you burn fossil fuel and which account for more than 80 per cent of the oil and gas companies’ emissions.

“They are trying to influence politicians,” said Hulse. “They’re saying, ‘You should throw money at us. You should make laws favourable to us.’”

Canadian anti-trust reforms should look to overseas solutions

Sandborn says adequate advertising provisions have been instrumental in several lawsuits filed against oil and gas companies in many U.S. jurisdictions.

Other jurisdictions have already moved to give government watchdogs more powers to enforce deceptive marketing practices around environmental claims.

In a statement Tuesday, former Minister of Environment and Climate Change Catherine McKenna said Canada should follow the lead of jurisdictions like the European Union to tackle “greenwashing head on.” McKenna, who now the current chair of a United Nations expert panel scrutinizing whether companies are engaged in greenwashing, said current anti-trust laws are creating barriers and preventing companies from advancing “climate goals through legitimate collaboration.”

“The current reform of the Competition Act is the perfect opportunity to do this,” she said.

“The Canadian government should set standards and enforce against greenwashing not only for the good of consumers and the planet, but also so our marketplace is not distorted by false or confusing green claims.”

Sandborn says France is one of the best examples of how tightening anti-trust laws can regulate greenwashing.

In 2021, the country amended its Criminal Code so that companies can’t claim goods are “carbon-neutral” unless they back it with publicly available information.

Those disclosures must show the greenhouse gases produced by a product or service includes both indirect and direct emissions. Companies making such sustainability claims also must show how they will avoid, reduce or offset those emissions. Failure to meet those requirements can lead to fines of up to $140,000.

“We have to set standards for climate claims. It’s not good enough to say we’re going to be net-zero by 2050,” said Sandborn.

“We don’t count the gas, which is the vast majority of the greenhouse gases.”

Sandborn points to a long and documented history of how industry misled the public about the impact of burning fossil fuels on the world’s climate system and that “they can’t be allowed to do it again.”

“False advertising laws have always been important to protect consumers,” said Sandborn. “We’re saying in this case, they’re also critically important to save the planet.”