A B.C. court has handed the Cowichan Tribes and other First Nations title over a chunk of federal and city land in Richmond that for centuries was used as a winter fishing village, before colonial administrators evicted the people who lived there.

The landmark Aug. 7 ruling was handed down after more than 500 days of litigation before the B.C. Supreme Court.

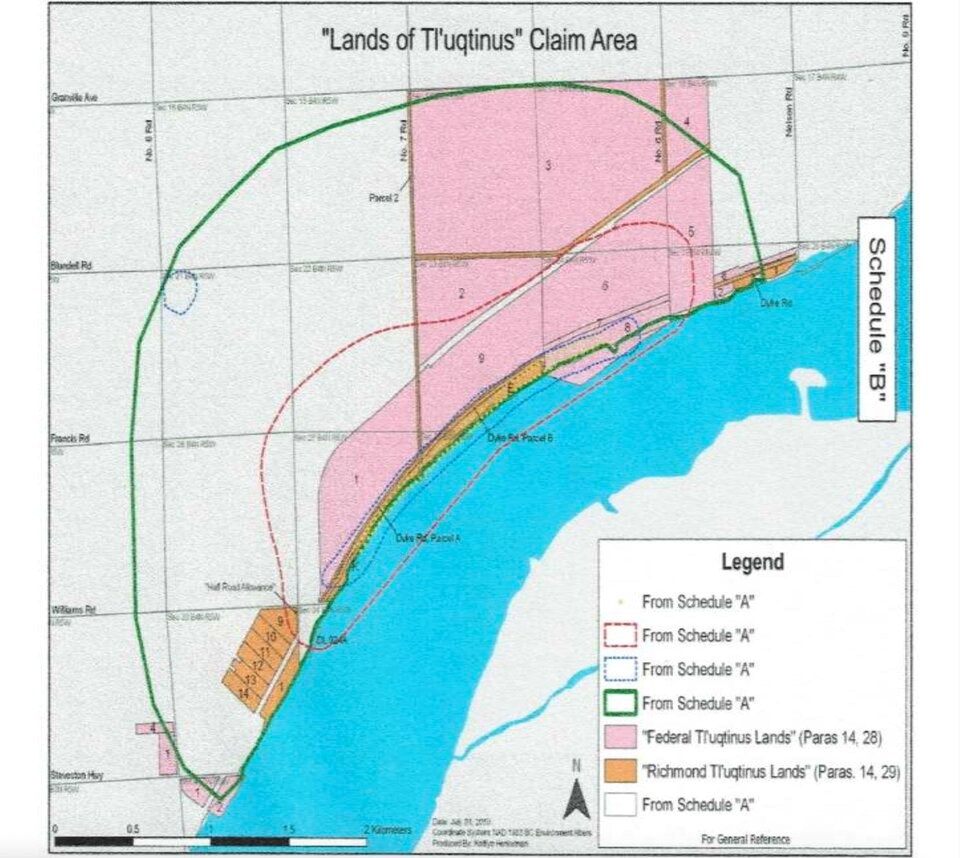

It gives the Cowichan Tribes, the Stz’uminus First Nation, Penelakut Tribe, Halalt First Nation — as well as the Lyackson First Nation in a supporting role — Aboriginal title over the Tribes’ historic Tl’uqtinus village on the southeast side of Lulu Island.

The ruling also gives the First Nations fishing rights at the mouth of the Fraser River.

In a joint statement, the First Nation plaintiffs said: “We raise our hands to the generations of leaders” who fought for the return of the Tl’uqtinus village lands and their fishing rights in the Fraser River.

B.C. Supreme Court Justice Barbara Young suspended her decision for 18 months “to allow for an orderly transition of the lands” in keeping with the principle of reconciliation.

“Now that this multi-year journey has concluded, it is my sincere hope that the parties have the answers they need to return to negotiations and reconcile the outstanding issues,” she wrote.

Multiple defendants opposed land claim

In a statement, B.C. Attorney General Niki Sharma said the “long and complex” decision was being reviewed by the province and that all parties had 30 days to decide whether they would submit an appeal.

As Sharma’s office reviews whether there are grounds for appeal, Premier David Eby said the province will look for an out-of-court resolution through negotiations with the all nations.

“But let me be clear: owning private property with clear title is key to borrowing for a mortgage, economic certainty, and the real estate market,” said Eby.

“We remain committed to protecting and upholding this foundation of business and personal predictability, and our provincial economy, for Indigenous and non-Indigenous people alike.”

Chief and council for the Musqueam First Nation said in a statement it “fundamentally disagrees” with the judgment. As a defendant, Musqueam had argued that the Cowichan historically sought their permission to fish in the region. But the judge found their relationship was co-operative.

Fishing rights handed to the Cowichan include all species used as food, or for social and ceremonial purposes.

The tribes’ Aboriginal rights now extend from the eastern tip of Annacis Island and Lulu Island to the mouth of the south arm of the Fraser River.

The federal Minister of Justice and Attorney General of Canada did not immediately respond to a request for comment. The City of Richmond, another defendant in the case, said it was reviewing the decision and it was too early to comment.

The ruling includes a large portion of a 1,846-acre land claim made at the southeast end of Lulu Island, as well as 146 acres of submerged shoreline.

Portions of the land are owned by the federal government and managed by Vancouver Fraser Port Authority. A map included in the ruling shows a land claim that overlaps with port terminals, yards filled with shipping containers and a number of warehouses, including one operated by Amazon. A spokesperson for the port said it was carefully reviewing the ruling and its implications.

The B.C. government granted some of the village lands to settlers. And in the 1930s, the City of Richmond acquired two lots when they were put up for public auction because of delinquent municipal taxes.

In court, the City of Richmond claimed no declaration of Aboriginal title should be made because the Richmond lands contain important municipal flood infrastructure that benefits its 230,000 residents.

A declaration would effectively expropriate land in Richmond without compensation and put $100 billion in infrastructure at risk, the city claimed.

However, Young found the lands owned by Richmond remain “unoccupied and undeveloped” except for a dike. The city-owned parcels are also the same land where the historic Cowichan village was located.

“The significance of this land to the Cowichan far outweighs its significance to Richmond,” wrote the judge.

Cowichan fished Fraser River for hundreds of years

In her decision, Young describes the Cowichan people sharing a “common way of life” — a shared language, culture and the seasonal practice of setting off in boats to cross the Strait of Georgia.

At the mouth of the Fraser River, the tribes would gather to fish, hunt and live, often with the ebb and flow of migrating salmon.

In submissions to the court, the Cowichan Tribes claimed the Lulu Island village included “bighouses” extending 1.6 kilometres along the riverbank, organized in rows with multiple neighbourhoods. Hundreds of canoes lined the beach, Young wrote in her ruling.

Lawyers for the Tribes relied on archaeological evidence, oral histories and historical maps and other records stretching back to first contact in 1792.

That year, records described Spanish explorers coming into contact with Cowichan people in Porlier Pass not far from their villages on Galiano and Valdes islands.

Young concluded the encounter showed Cowichan had been migrating to the Fraser to fish for some time.

By 1846, evidence confirmed the Cowichan came from Vancouver Island and the Gulf Islands in large numbers to the Fraser River to fish, wrote Young.

“I find an estimate of 2,250 Cowichan occupying the village is reasonable because the 1,000 warriors would have brought family to assist them with resource harvesting and processing,” the judge said.

Evidence presented in court suggested that by 1877, the village still retained at least 1,000 Cowichan people. By then, tens of thousands of gold seekers had spent 20 years in the lower Fraser Canyon.

As gold miners diverted creeks into canals to separate the precious metal from gravel, salmon spawning was disrupted. The influx of miners also led to violence against Indigenous peoples, the ruling said.

Cowichan village caught up in mass dispossession of Indigenous land

The Cowichan title lands on Lulu Island were taken from the First Nation between 1871 and 1914, when the Crown granted legal control over the property to settlers. The result was to turn the Cowichan into trespassers on their own village land, the ruling said.

Still, even by 1901, a reverend who lived among the Cowichan on Vancouver Island found their villages deserted during the Fraser sockeye runs. Young found the Cowichan likely occupied the village on Lulu Island into the 20th century, though that was not needed to establish Aboriginal title.

Under colonial domination, the Cowichan Tribes submitted that the Crown forcibly controlled them through the creation of reserves, Indian agents and the residential school system.

Cultural practices, customs, and traditions were banned, and Indigenous people were denied access to their traditional territories, they claimed.

“Colonial administrators wanted the Cowichan to abandon their traditional way of life and live like colonizers on plots of land with fences,” wrote the judge. “The pass system confined the Cowichan to their Vancouver Island and Gulf Island reserves.”

The judge noted that evidence provided to the court shows that the Cowichan maintained a “substantial connection” to their land, which they have not abandoned today.

“Since at least the late 1800s, the Cowichan have been actively seeking recognition of their interests in the Lands of Tl’uqtinus,” wrote the judge.

Young added that handing over the Cowichan’s village lands constituted their “permanent displacement,” while ongoing infringement of Aboriginal title amounts to “continuing trespass.”

She ordered Richmond’s title over the historic Cowichan lands to be declared “defective and invalid.” The court order also requires the federal government and the Vancouver Fraser Port Authority to focus discussions on transferring the land to the Cowichan.

The Tribes’ consent will be required for any use of the land, the judge added.

“It will remain open to the Crown and local governments to seek the consent of the Cowichan in the future with respect to proposed improvements,” Young said.