With so many new developments changing the landscape of Squamish, it can be hard to spot the landmarks that were built long ago. One, tucked away behind a line of trees that help shield it from the road in Brackendale, is Judd Farm.

The three-storey, six-bedroom house sits on three and a half acres. A covered porch looks over the expansive backyard and a cherry tree. A wood-burning fireplace in the centre of the first floor is still relied on to heat the large old house, and a clawfoot tub sits in the upstairs bathroom. The master bedroom, in the attic, once housed 14 farmhands. When a door swings open — with no one nearby to touch it — owner Tamara Stanners says it must be one of the ghosts.

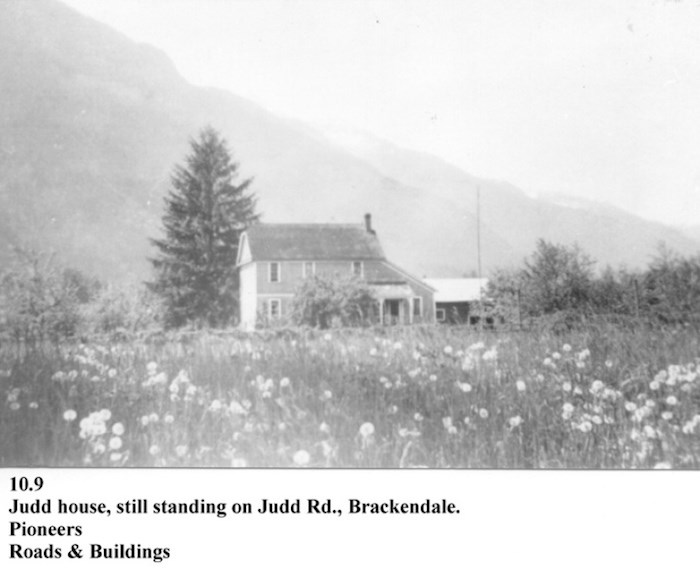

The Judd Farm after 1916. Photo courtesy Squamish Digital History Collection/Squamish Public Library

The Judd Farm after 1916. Photo courtesy Squamish Digital History Collection/Squamish Public Library

Stanners and her husband Lorne Badger are the current owners of the property. After purchasing it in 2000 from the direct descendants of Henry and Anna Judd, who built the house, Stanners and Badger are the first people not related to the original family to own Judd Farm.

The couple was commuting from West Vancouver to the coffee shop they'd started in Brackendale, then known as the Eagle Run Coffee Company (where Bean Around the World is today). As they were looking for a place to live in Squamish, Badger stumbled across the Judd farm property. It wasn't for sale — but, as Stanners tells it, the ‘for sale' sign went up the next day.

It took a while to convince the Grants to sell to them, Stanners said, because of their close attachment to the house and their concern someone would knock it down to develop on the land.

"It's like a member of the family," Stanners says now, nearly 20 years later. "You want to protect it and keep it safe."

The year the house was rebuilt after a fire depends on who you talk to, Stanners said, with estimates ranging from 1914 to 1916. At any rate, the current house is more than 100 years old.

"The whole community, from what we understand, came together to rebuild it very quickly after it burned down," Stanners said. "It was, from all accounts, a really amazing community hub. It held all kinds of meetings and all kinds of parties and it was a real gathering place for the community, which it has tended to remain to be. With the energy of the house, it definitely attracts people."

But by the time Stanners and Badger bought the house, it was showing its years.

In the 1960s, the owners decided that they wanted to modernize it. That was when aluminum windows and sliders were installed. Plexiglass was added to seal in the porch, and tile became the new flooring with shag carpet on top. The carpet was still there when Stanners and Badger moved their family in.

"A lot of people thought the house should have been condemned, actually, when we bought it because it was in such disrepair," Stanners told The Chief. "It was slanted at an angle... If anything dropped on the floor, it would roll right down, through the floorboards and into the basement."

Their repair plan was to stay as true to the house as possible.

"I actually love walking through the yard and mowing the grass, because you can smell all the different sorts of crops that they planted," she said of the farm property, adding that the hops still grows wild.

They had to remove some diseased trees, but were able to keep some fruit trees. The roof was replaced with a metal one from Fraser Wharves, like many pieces sourced by Badger for the renovation that came from other old properties — or even inside the Judd Farm.

When he took down the siding, Badger uncovered where the original windows had been boarded up. The kitchen walls blocking the old windows became cabinetry.

All told, the renovations took five years. When they were done, the family invited Ellen Grant, the granddaughter of the Judds and the most recent owner, over to see the house's transformation. As she stepped inside, Stanners said, Grant began to cry, and told them it looked just as her grandmother had kept it.

"She thanked Lorne for taking the time and care to put it back together again," Stanners said.

The house still acts as a default gathering place, as the site of weddings, a rotating door of visitors and legendary music-filled parties that Stanners said kept getting shut down by the cops after noise complaints. (Now, she's one of the organizers behind the much bigger music-filled Constellation Festival, which kicks off later this month.)

The Judd Farm literally acts as well, taking on a starring role in numerous film productions including many Hallmark movies and the TV show Men in Trees' pilot episode. The show later built a replica of the house for the set. Most recently, the house was briefly painted green and black for the to-be-released horror film Antlers.

"It was just so gross and it broke my heart every time I looked at it, but it is back to yellow," Stanners said. "It's amazing to watch transformations like that."

Stanners credits former mayor Patricia Heintzman for putting the house on a film website as a potential shoot location.

During the holidays, the family will gather to watch Hallmark Christmas movies the house has starred in. But that's not the most important role the house has played, at least not to Stanners.

The Judd Farm today. Photo by Keili Bartlett/The Squamish Chief

The Judd Farm today. Photo by Keili Bartlett/The Squamish Chief

"What I care about most, I think, is the fact that it has played such a role in the development of the community. Throughout its entire life, it housed people who worked on stagecoaches that were delivering goods and to be the first home of the European pioneers who came here," she said, adding she also thinks of the First Nations people who were here first, and how hard it would have been to see the changes.

"Every day there can be new thoughts about what it is to be in this house and who has lived here before. The energy and the spirits who still are here. We don't take it lightly. We really love this place."

When asked what she thinks about the lack of a heritage policy in Squamish, Stanners said she tries to think about it from all sides.

"It hurts to see how so much of Vancouver's heritage is gone," she said, before talking about how the Judds went through changes themselves. First they built a house lower on the property, but it kept flooding. This house was built after a fire. Even this property has always been changing, throughout its 100-plus-year history.

She acknowledges that the recent growth of Squamish requires more changes still.

"That's what I'd like to see is just balance and keeping what makes sense to keep. What is structurally sound to keep, what works. And also build the buildings that are going to be efficient to run and sustainable. Balance is everything," Stanners said.

For the Judd Farm, though, she said, "If this house were not structurally sound, if there was a problem with it, it would be hard to think that we wouldn't have the say on how we fix it or what to do with it. There's really a balance. It would be nice to think people who buy property or owners would value history as much as say I do and Lorne does. But I don't know if that's the case."

She suggests an individual basis for the historical sites left in Squamish, something that can accommodate the preservation of heritage and the needs of the current population.

"I do think it's a piece of history," Stanners said of her family's home. "There's no way you can replace what this is, you just can't."