Before the first Second Narrows Bridge crossed Burrard Inlet there was no way to get from Vancouver to the north shore unless you had a boat.

When developers and residents of the north shore pushed for a fixed link to the rest of Metro Vancouver a bridge proposal came forward, for rail and vehicles, and a bridge was eventually built, opening in 1925. It's since been replaced.

However, that bridge wasn't the only proposal; a mega project that would have significantly changed the region was put forward as well in 1912 and 1913.

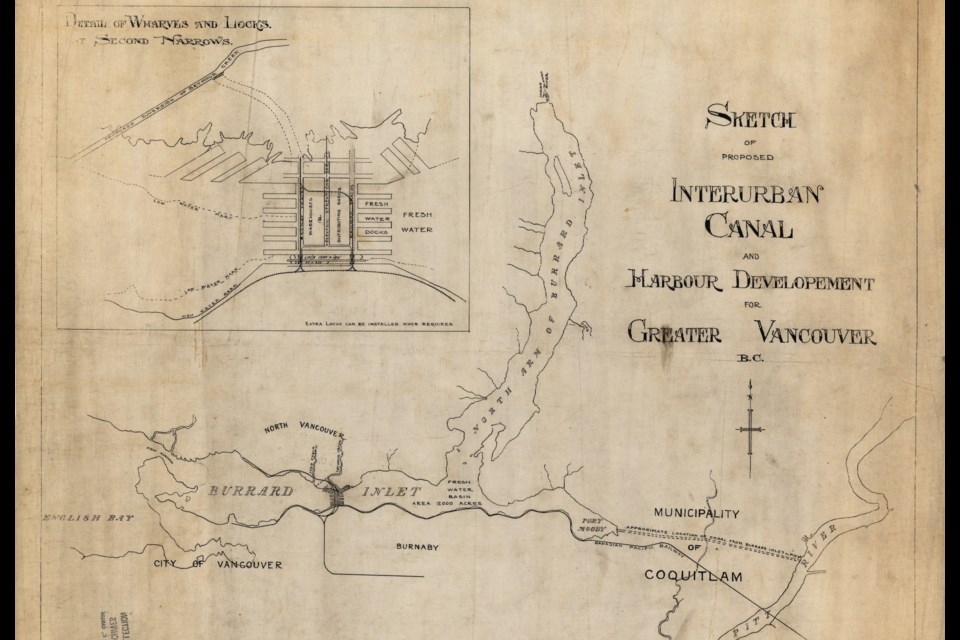

The project was never built so it wasn't given a catchy name. Instead, the concept was called a few things, including the "Interurban Canal" and "Harbour Development for Greater Vancouver."

The basic idea was simple, though pulling it off would have been much more complex.

There would have been two parts to the plan: a freshwater canal and a set of locks in Burrard Inlet.

The Burrard Locks

The locks at Burrard Inlet's Second Narrows would have been a huge infrastructure project unlike anything else on Canada's west coast at the time.

The site would have become a massive shipping hub between the northern edge of Boundary Road and the southern end of Seymour Creek, connecting North Vancouver to the City of Vancouver and Burnaby.

The locks themselves would have actually only a small part of the massive structure, with two on the southern side.

Most of the width of Burrard Inlet would have been blocked by a new piece of land. That area wouldn't have been small either, with space for several warehouses, docks for ships, offices, a power plant, roads, and railways factored into the plan.

This was to be a solid dam as well, blocking the water and turning the eastern portion of Burrard Inlet, including Indian Arm, into a freshwater basin (essentially a lake). Nowadays this probably wouldn't move very far because of the ecological effect it would have on the region, but it wasn't a significant concern over a century ago.

Because the eastern portion of Burrard Inlet would no longer experience tides, it was expected significant chunks of land could be "reclaimed" and used for industry near the locks, while Port Moody's mudflats could be flooded and made more useful to infrastructure and industry.

The Coquitlam Canal

The canal was never named, but given its route, it would make sense to call it the Coquitlam Canal, since it would have travelled more than 10 km from Pitt River through Port Coquitlam and Coquitlam. The region was sparsely populated at the time and those proposing the route figured the land was available.

This would have given a new freshwater route for shipping out of the region's inland areas to the city's harbour, which had become the major port at the time.

Vancouver had also just seen a massive population boom, jumping from 26,000 residents in 1901 to 100,000 in 1911.

The route of the canal was never nailed down, but it would have run from the very western edge of Burrard Inlet in Port Moody to Pitt River near where it meets with Alouette River. This would have given it a similar route to that of Highway 7, only further north.

What happened to the idea?

The idea of canals connecting waterways in Vancouver had been around since the earliest days of the city; the city's second mayor, David Oppenheimer, was reportedly a proponent.

However, around 1910 to 1912 the debate was getting more consideration as people in North Vancouver, which had been incorporated in 1907, wanted easier access to the city. While a bridge had been proposed, the locks and canal system was in the running, with an engineering firm drawing up designs.

In October 1912, a group including federal, provincial, regional, and municipal officials and politicians went for a tour of the part of the canal route with a Coquitlam councillor speaking on behalf of the project.

Costs were estimated at $5.5 million. It's hard to determine how much that would have been today as the Bank of Canada's inflation calculator only goes back to 1914, but it would have been north of $150 million.

At the same time, North Vancouver residents were pushing for a swing bridge, which had already been approved by the time the canal and locks system's proponents were getting material out.

The issue went to the Board of Trade in January of 1913 and it's unclear what happened there, but there was pushback against the scheme as the bridge plan had advanced so far.