CEDAR RAPIDS, Iowa (AP) — The oldest surviving place of worship for Muslims in the United States is a white clapboard building on a grassy corner plot, as unassumingly Midwestern as its neighboring houses in Cedar Rapids – except for a dome.

The descendants of the Lebanese immigrants who constructed “the Mother Mosque” almost a century ago — along with newcomers from Afghanistan, East Africa and beyond — are defining what it can mean to be both Muslim and American in the nation's heartland just as heightened conflicts in the Middle East fuel tensions over immigration and Islam in the United States.

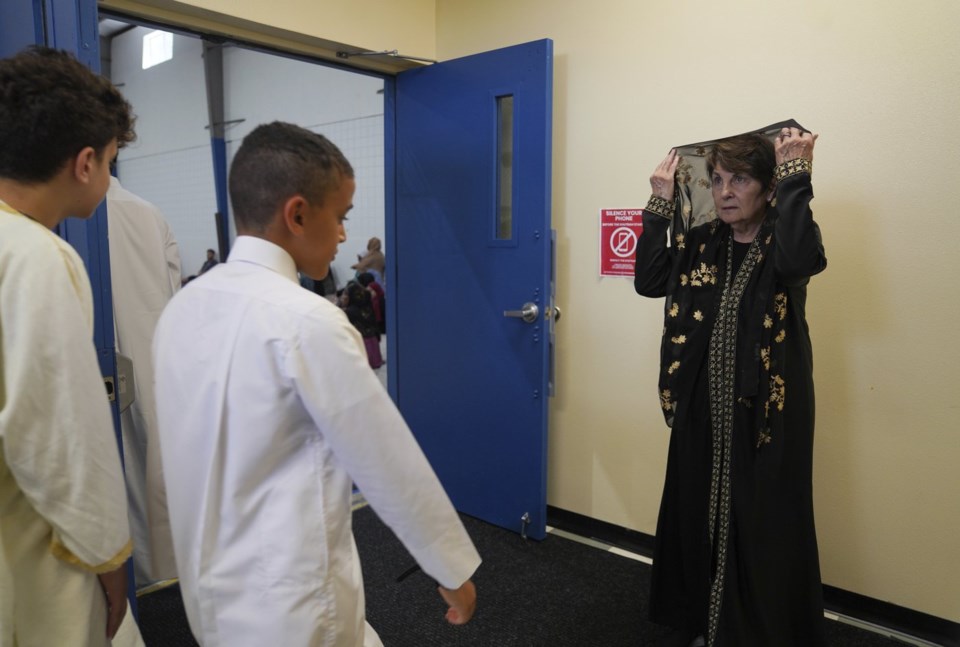

Standing by the door in a gold-embroidered black robe, Fatima Igram Smejkal greeted the faithful with a cheerful “salaam” as they hurried into the Islamic Center of Cedar Rapids for Friday prayers. In 1934, her family helped open what the National Register of Historic Places calls “the first building designed and constructed specifically as a house of worship for Muslims in the United States.”

“They all came from nothing … so they wanted to give back,” Smejkal said of families like hers, who arrived at the turn of the 20th century. “That’s why I’m so kind to the ones that come in from Somalia and the Congo and Sudan and Afghanistan. I have no idea what they left, what they’re thinking when they walk in that mosque.”

The community now gathers in the Islamic Center. It was built in the 1970s when they became too many for the Mother Mosque’s living-room-sized prayer hall, and now they’re have outgrown its prayer hall, as well. Hundreds of fifth-generation Muslim Iowans, recent refugees and migrants pray on industrial carpets rolled onto the gym’s basketball court — the elderly on walkers, babies in car seats, women in headscarves and men sporting headgear from African kufi and Afghan pakol caps to baseball hats.

This physical space where diverse groups gather helps sustain community as immigrants try to preserve their heritage while assimilating into U.S. culture and society.

“You can be a Muslim that’s practicing your religion and still coexist with everybody else around you,” said Hassan Igram, who chairs the center’s board of trustees. He shares the same first and last names as his grandfather and Smejkal’s grandfather – two cousins who came to Iowa as boys in the 1910s.

Lebanese migrants ‘Mother Mosque’

Tens of thousands of young men, both Christians and Muslims, settled in booming Midwestern towns after fleeing the Ottoman Empire, many with little more than a Bible or a Quran in their bags. They often worked selling housewares off their backs to widely scattered farms, earning enough to buy horses and buggies, and then opened grocery stores.

Through bake sales and community dinners, a group of Muslim women raised money in the 1920s to build what was called the “Moslem Temple.” Like the Igrams, Anace Aossey remembers attending prayer there with his parents – though as children they were more focused on the Dixie Cream donuts that would follow.

"We weren’t raised real strict religiously,” said Aossey, whose father sold goods along the tracks from a 175-pound sack. “They were here to integrate themselves into the American society.”

Growing up Muslim in America

Muslims sometimes faced institutional discrimination. After serving in World War II, Smejkal’s father, Abdallah Igram, successfully campaigned for soldiers’ dog tags to include Muslim as an option, along with Catholic, Protestant and Jewish.

But in Cedar Rapids, immigrants found mutual acceptance, fostered through houses of worship and friendships between U.S.-born children and their non-Muslim neighbors. Smejkal's best friend was Catholic, and her father kept beef hot dogs in the kitchen to respect the Muslim prohibition against pork. Smejkal's father, in turn, made sure Friday meals included fish sticks.

“Arab-speaking Muslims were part and parcel of the same stories that inform our sense of what the Midwest is and its values are,” said Indiana University professor Edward E. Curtis, IV. “They participated in the making of the American heartland.”

Abdallah Igram is buried in the city's hilltop Muslim cemetery, among the first in the United States when it was built in the 1940s. It's next to the Czech cemetery – for the descendants of the migrants who helped establish Cedar Rapids in the 1850s — and the Jewish cemetery, whose operators donated trees to the Muslim one after damage from a derecho five years ago. Smejkal wishes the whole world's faiths could collaborate this way.

“That’s when there’s no barriers anymore. I pray one day it’s really like that,” Smejkal said.

Being Muslim in the Heartland

The Muslim presence across the Midwest grew exponentially after a 1965 immigration law eliminated the quotas that had blocked arrivals from many parts of the world since the mid-1920s, Curtis said.

Mistrust flared again after the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks, especially in farming communities whose young people were fighting in Afghanistan and Iraq, said Ako Abdul-Samad, an African-American who represented Des Moines for nearly two decades in the Iowa House of Representatives. He feared being Muslim would prevent his election when he first ran for office, but voters re-elected him again and again.

Immigration, including from Muslim countries, remains a contentious issue, even as Muslim communities flourish and increase their political influence in major cities like Minneapolis and Detroit.

But daily interactions between Muslims and their neighbors have provided some protection from prejudice, according to the Mother Mosque imam, a Palestinian who immigrated in the 1980s. “Stereotypes and things did not work” in Cedar Rapids, Taha Tawil said.

Bosnian Muslims say they’ve had similar experiences near Des Moines, where a new multimillion dollar mosque and cultural center is opening next month, an expansion of the first center established by war refugees 20 years ago.

“Our neighbors have been great to us, including the farmers we got the land from,” said its treasurer, Moren Blazevic. “We’re finally Iowans.”

Becoming Midwesterners

Faroz Waziri jokes that he and his wife Mena might have been the first Afghans in town when they came in the mid-2010s on a special visa for those who had worked for the U.S. armed forces overseas. After struggling with “culture shock” and language barriers, they've become naturalized U.S. citizens, and he's the refugee resources manager at a non-profit founded by Catholic nuns.

While grateful for the aid and the safety they feel, the Waziris miss their families and homeland. And they fear that cultural differences — especially the individualism Americans express, like when they sit around a table for meals, instead of together on a rug — remain too vast.

“Mentally and emotionally, I never think I’m American,” said Mena Waziri. She's a college graduate now, and loves the independence and women's rights that remain unattainable in Taliban-run Afghanistan. But the family is keen for their U.S.-born son, Rayan, to have Muslim friends and values.

These tensions are familiar for the descendants of the city's first Muslim settlers, like Aossey, who keeps exhibit panels about Lebanese immigration and integration in the same garage where he stores ATVs on his recreational farm.

“My story is the American story," Aossey said. “It’s not the Islamic story.”

___

Associated Press religion coverage receives support through the AP’s collaboration with The Conversation US, with funding from Lilly Endowment Inc. The AP is solely responsible for this content.

Giovanna Dell'orto, The Associated Press