SkyTrain has ended at King George station since 1994, but plans are underway to see the line extended to Fleetwood by 2025. Photo by Rob Kruyt/BIV

SkyTrain has ended at King George station since 1994, but plans are underway to see the line extended to Fleetwood by 2025. Photo by Rob Kruyt/BIV

With Metro Vancouver’s population expected to increase by about one million people to around 3.6 million residents by 2050, the region needs transportation infrastructure upgrades to ensure road gridlock does not stall the economy.

The drawing board is replete with scribbles for new bridges, expanded roads and SkyTrain extensions. All the proposed projects have been carefully studied; some were abruptly halted so they could be restudied and revamped.

Much of this extensive planning is aimed at the region’s notorious traffic gridlock during rush hour, when drivers attempt to pass through the George Massey Tunnel.

One of former premier Christy Clark’s first big announcements, in 2013, was that her government would stop endless dialogue and replace the tunnel with a 10-lane, $3.5 billion bridge.

However, in 2017, the new BC NDP government quickly scrapped the project. In its place, the government launched what it called an “independent technical review” to research how to best replace the aging tunnel that experts have called unsafe and vulnerable to potentially collapse during an earthquake.

Sturdy accuses the NDP of scrapping the George Massey crossing for political reasons and to spite former premier Clark, but when BIV asked Transportation and Infrastructure Minister Claire Trevena, she rejected that thesis.

She called the crossing a “problem,” but stopping the bridge project was appropriate because “the previous government had pushed ahead without agreement from the local communities, the local mayors.”

Some politicians in the region, however, such as former Delta mayor, and now councillor, Lois Jackson, lobbied hard for a bridge and praised the initiative.

A government website during the summer said that project is in the “solution development” phase. Sturdy said it has been studied to death.

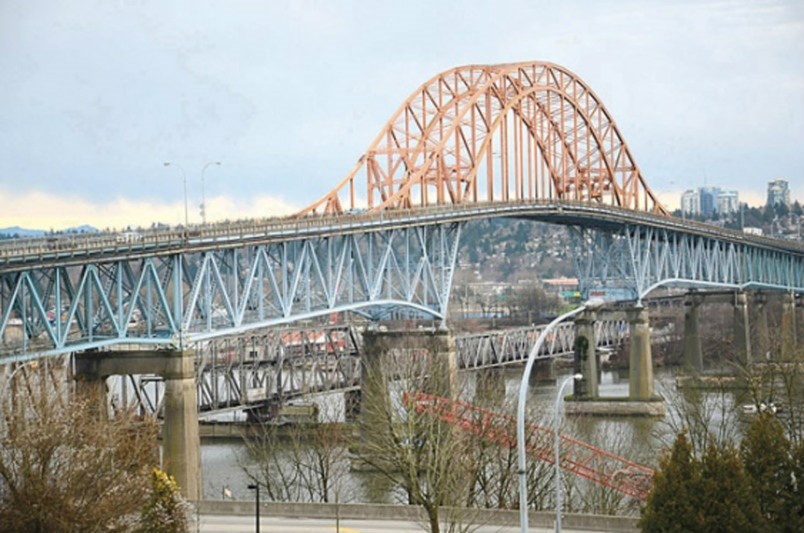

The $1.4 billion proposal to replace the Pattullo Bridge offers a stark contrast. The B.C. government took over the project from TransLink and greenlighted the project in 2018.

Pattullo Bridge. File photo/New Westminster Record

Pattullo Bridge. File photo/New Westminster Record

Work is set to begin this year and take four years, with a requirement that all work on the bridge be done by unionized labour – a proviso critics say could add $100 million or more to the total bill.

Sturdy claimed extra costs have forced the government to delay or scrap other road improvements around the province. He pointed to the Mile 28 level rail crossing on Highway 18 near Prince George as an example.

Public transit

Recent elections have also redrawn the public infrastructure map in Surrey.

Longtime Surrey mayor Dianne Watts started lobbying in 2011 for light rail on three major corridors in her city.

“I don’t want to have SkyTrain cutting our communities in half,” she said in her 2011 state-of-the-city speech. “That is going to destroy our city.”

Linda Hepner became mayor in 2014 and promised to have a light-rail system running by 2018.

“I am incredibly confident,” she said in a media scrum after her election. “I am building that light rail.”

Approvals followed. Surrey spent $20 million to plan and carry out pre-construction work, while TransLink spent about $50 million. Light rail appeared to be a sure thing.

But when Doug McCallum won the 2018 mayoral race, he slammed the brakes on the project, saying he favoured the more expensive SkyTrain.

TransLink noted that the available $1.6 billion in funding could not cover the $3.12 billion cost of building SkyTrain to Langley from Surrey. Metro Vancouver’s Mayors’ Council on Regional Transportation voted to start planning for the Surrey SkyTrain project even if it had to be built in two phases, with the first leg being a seven-kilometre, four-station extension to Fleetwood.

That council is expected to give the project final approval in January, with public consultation on SkyTrain to Fleetwood set to start in the fall.

If senior governments then approve the business case, construction is possible as early as 2022, and service launching as early as 2025.

Other SkyTrain extensions are also in the works. Construction is set to begin in 2020 on Vancouver’s six-station SkyTrain extension on Broadway that will stretch to Arbutus Street, from the end of the Millennium Line at Clark Drive. TransLink expects it to also be ready to ride by 2025.

The next SkyTrain extension is likely to extend the Millennium Line to the University of British Columbia (UBC), although the money is not yet in place.

SkyTrain. File photo

SkyTrain. File photo

Vancouver city council voted in January to support building SkyTrain to UBC, and the Mayors’ Council added its support for that extension the following month. Polling has showed that 87% of Metro Vancouverites support building SkyTrain to UBC even though it comes with a $3.8 billion price tag.

“The next round of study, which should be completed within a year or so, will be to identify the kind of guideway – whether it is above ground or a tunnelled SkyTrain to UBC,” TransLink CEO Kevin Desmond told BIV.

Expansions to North Vancouver or Port Coquitlam are “great ideas,” after SkyTrain extensions to UBC and to Langley are complete, Desmond said.

He called for a new 30-year plan because the last time the region did a comprehensive regional plan was in 1993, and virtually everything in that plan has either been built or will be built, he said.

“What do we do with commuter rail?” Desmond asked. “I’m a firm believer that we need to make commuter rail even bigger in this region.”

TransLink’s contract with Canadian Pacific Railway (TSX:CP)allows it to run the West Coast Express only during rush hours on weekdays because the tracks are needed for freight at other times.

With freight capacity expected to increase, Desmond does not want to see commuter rail get squeezed. He’d prefer to expand the rail network to better move goods and people.

Last week, he suggested to BIV that he would like the federal government to pass a law to mandate that 20% of gas tax revenue, or some other guaranteed amount of money, get earmarked for transit.

Roadwork

Plenty of road improvements are being studied, including a re-engineered Granville Bridge in Vancouver.

Of the projects underway, many were in planning stages before the NDP came to power, Sturdy said. For example, there are $245 million in highway and road improvements in Delta that began last year. This spending involves five major changes on three interconnected road corridors that the government says will reduce travel times for container-truck drivers who service GCT Deltaport, and better connect communities south of the Fraser River.

Included are upgrades to Highway 91, Highway 91 Connector, Highway 17 and Deltaport Way/27B Avenue.

Current design of the Granville Bridge. Image courtesy City of Vancouver

Current design of the Granville Bridge. Image courtesy City of Vancouver

On the North Shore, Phase 1 of the $198 million Highway 1/Lynn Interchanges project is nearly complete. Work includes construction of a westbound collector lane to Mountain Highway from Mount Seymour Parkway, a new bridge on either side of the existing Lynn Creek Bridge and an eastbound on-ramp from Mountain Highway onto Highway 1.

The aim of the upgrades is to improve safety and traffic flow along Highway 1 between Mountain Highway and the Second Narrows Bridge – another of the biggest bottlenecks in the Lower Mainland.

Langley is the third area where long-planned roadwork is moving ahead.

The B.C. government is spending $61.9 million in Langley to add lanes to part of Highway 1, making it a six-lane thoroughfare between 202 and 216 streets – an initiative also known as the 216 Street Interchange project.

It is also spending $205.5 million to widen the next 10 kilometres of the highway, to 264 Street. When done, there will be a 44-kilometre-long stretch of high-occupancy-vehicle lanes between Burnaby and Langley.

A third Langley project is a $25.5 million initiative to widen Highway 13 between 8 Avenue to 0 Avenue, improve intersections and add new pedestrian and cycling facilities. That is expected to provide additional capacity at the Aldergrove-Lynden border crossing, improve the movement of people and goods and increase tourism, trade and economic growth, according to the province.

The $22 million project to widen Mount Lehman Road to four lanes in Abbotsford is intended to include intersection improvements and better lighting on the main route to Abbotsford International Airport, and a street that also connects to the U.S. border.