Chinook salmon caught off Vancouver Island. V.I.A. file photo

Chinook salmon caught off Vancouver Island. V.I.A. file photo

A recent Department of Fisheries and Oceans (DFO) decision to close some B.C. areas to all recreational fishing this summer and implement restrictions on chinook salmon in others is a half measure that misses the boat, fisheries and marine mammal experts say.

In a move aimed at conserving declining chinook stocks, which make up 90% of the southern resident killer whale’s diet, the DFO has closed three orca foraging areas to all finfish angling: on Vancouver Island, from north of Sooke to Port Renfrew, the Gulf Islands and the mouth of the Fraser River. The DFO is also implementing zero retention for chinook in the Prince Rupert region and restrictions for chinook for the Nass and Skeena rivers. The closures and restrictions are aimed at reducing the chinook catch by 25% to 35%.

Without also restricting whale-watching in sensitive marine areas, the initiative could hurt B.C.’s sport-fishing sector with no guarantee of helping killer whale populations.

Alaska’s Department of Fish and Game last week also began instituting full chinook sport-fishing closures for some river systems. The B.C. closures will have a big impact on lodges, charters, guides and other businesses in the sport-fishing sector, said Owen Bird, executive director for the Sport Fishing Institute of BC.

“I don’t think even ‘devastating’ is too strong for these small communities that really rely on the sport-fishing economy,” Bird said.

Greg Taylor, a fisheries adviser and member of the salmon sub-committee of the Marine Conservation Caucus, said the closures and restrictions are half measures, partly because they don’t include a ban on whale-watching boats in critical orca foraging zones. Leaving some areas open to chinook fishing and others closed just redistributes the catch, Taylor said, so the closures are more about giving orcas room to feed than reducing chinook harvest levels.

Of 15 chinook conservation units, 11 are designated red (status poor). Neither of the units in the Nass and Skeena is red, so Taylor wonders why restrictions on chinook have been implemented there but not on the entire Fraser River system.

“If you look at how many chinook are returning to the Fraser River right now, no one should be fishing – no one,” Taylor said.

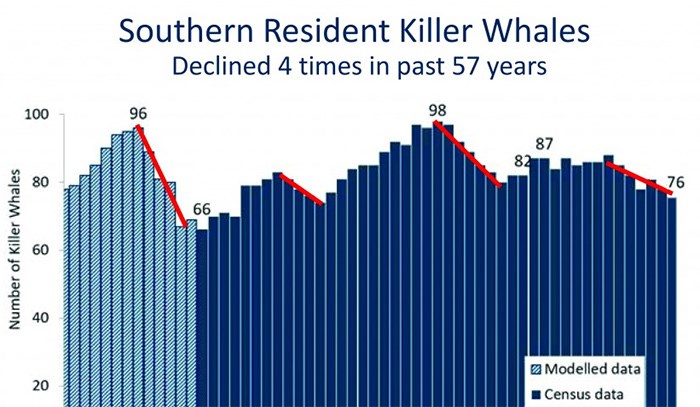

The southern resident killer whale population has fallen to 76 from a high of 98 in the mid-1990s.

B.C.’s southern resident killer whale population has declined and rebounded four times since 1960

B.C.’s southern resident killer whale population has declined and rebounded four times since 1960

A science panel struck to study the decline concluded in 2012 that fewer chinook isn’t the only challenge orcas face. If there is too much noise from small-boat traffic, they can’t use eco-location to hunt, so it might not matter how much fish is in the water if they can’t catch them.

Andrew Trites, director of the Marine Mammal Research Unit at the University of British Columbia, said the discussion over southern resident killer whales is being oversimplified.

While 76 is lower than average for the southern resident killer whale population, it has been lower than that. Over the past 58 years, that population has declined and rebounded four times, never going above 98.

Meanwhile, Trites said the northern resident killer whale population has grown to about 300. Their range overlaps, with the northern orcas coming as far south as Vancouver Island, so why is the southern population doing poorly while its northern counterpart is thriving?

“The simple narrative is always ‘It’s overfishing,’” Trites said. “Yet the truth of this story might be competition from northern residents. We’ve got increasing sea lion populations, we’ve got very abundant harbour seal populations. So on many levels, we’ve got an ecosystem for marine mammals that’s great, but we’ve got this one outlier that’s doing not well, and that’s the southern residents.

“You would expect that, if it was just a straight-up lack of prey, that the northerns should also be affected, and we’re not seeing that. And so it’s very possible that the northerns are excluding or pushing the southern s further south into marginal habitat.”

@nbennett_biv