|

Print Matters is a celebration of the printed form and all the awesome local people who bring it to you: literary journals, publishers, magazines, small presses, book artists, and independent booksellers. |

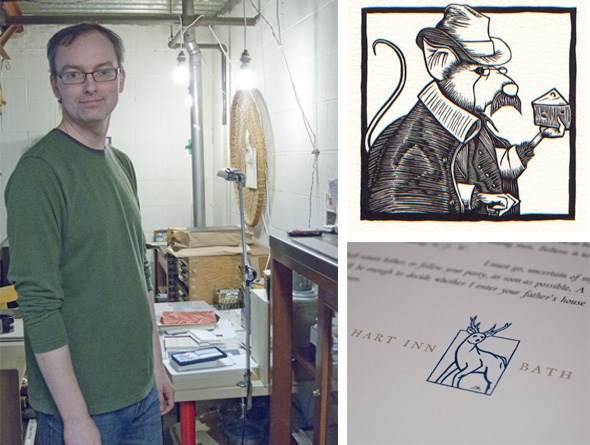

| Working away in cramped studios, industrial parks, backyard sheds and small apartments are many talented artisans in Vancouver who use letterpress printing as their creative tool. This week Jarrett Morrison talks about the road that led him to his vocation, why his letterpress is named Beryl, and how a BBC panel discussion three years ago led to his latest project and dark thoughts about eating the baby. |

I met up with Jarrett Morrison at Rasmussen Bindery in North Vancouver. It's here, in a nondescript ubiquitous cinder block building in the waterfront industrial area south of Marine Drive, that he runs The Bowler Press, an imprint that crafts limited-edition books, broadsides and collectibles. Founded in 2007, the press's output so far has been modest, but impressive, considering Morrison does everything himself, setting the type, printing, creating and carving the illustrations, and binding the work, as well as looking after his two young daughters.

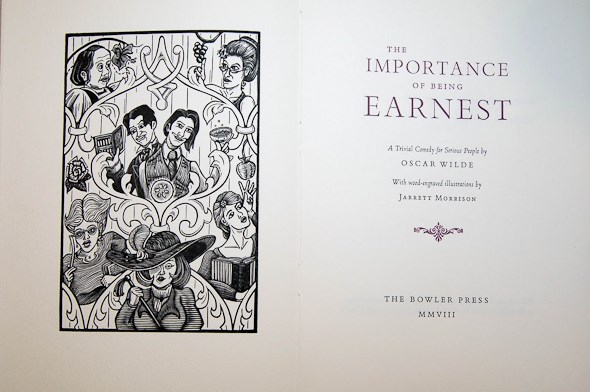

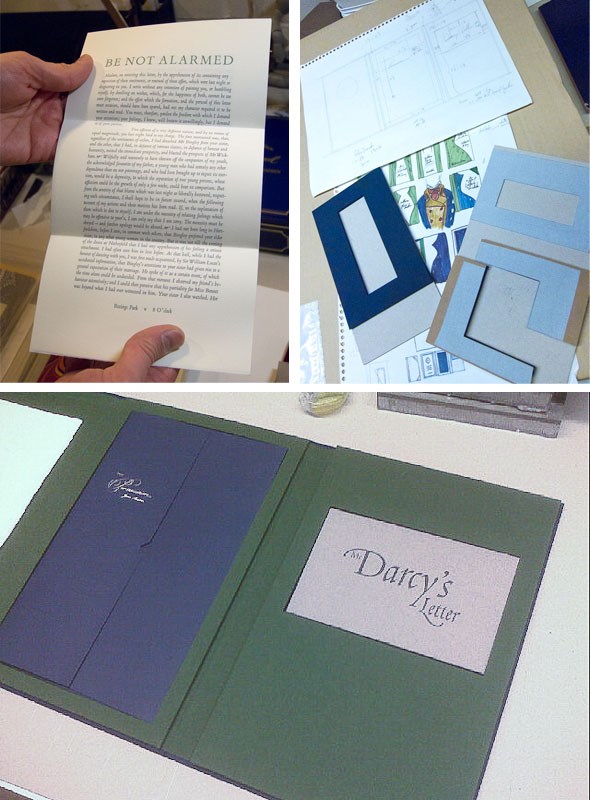

His first major piece was a broadside, "Chesterton Cheese," which consisted of a quote from C.K. Chesterton's Alarms and Discursions and an engraving by Morrison. This was followed by his first letterpress printed book, The Importance of Being Earnest by Oscar Wilde in 2009. Next came two letters from the work of Jane Austen: Captain Wentworth's letter from Persuasion and Mr. Darcy's letter from Pride and Prejudice. These two smaller pieces provide the lead up to an ambitious project that Morrison will undertake, starting later this year: a 3-volume presentation of Pride and Prejudice itself. But first he has to finish his latest, Jonathan Swift's satirical essay, A Modest Proposal.

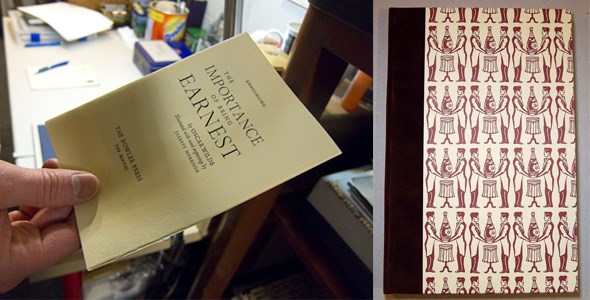

The announcement for The Bowler Press's first book, Oscar Wilde's The Importance of Being Earnest, and the finished book.

The announcement for The Bowler Press's first book, Oscar Wilde's The Importance of Being Earnest, and the finished book.

What is your background and how did your interest in letterpress begin?

I grew up in Ontario. My wife was from Vancouver, grew up in Surrey. We came here in 2002 and she found a job at St. Paul's as a research coordinator. And the first thing I did when I got here was to pick up a job doing something I had done on the sideline since high school and through university which was working in trade show graphics. It was very handy in terms of all the skills and manual dexterity that are required and that sort of just fed into what I am doing now. I didn't like it, though, and I ended up changing jobs and just working at a local market. And I did that for 3 years until it closed.

During that time I did a 3-week job exploration program, specifically geared towards the arts. At that time I was already thinking about taking my own writing in some direction. There was a youth book I was trying to work on, but I decided to explore a little bit more in terms of book arts. It started with an introductory course on bookbinding that was being taught at Emily Carr from Terry Rutherford. It was the Coptic style binding, the kind with the invisible stitching, open back, where the book is sewn to the boards.

I then looked at the offerings from the Canadian Bookbinders and Book Artists Guild and found a four-day long workshop, Introduction to Design and Letterpress Printing, being offered at Barbarian Press in Mission. It was a bit more of a commitment, but I signed up and there was space for me. In the end there were four students and it was a comfortable number. By the Thursday, and we were going to wrap up on the Friday, I really had no idea how I was doing in terms of the process and taking everything in and being able to execute what I needed to do to produce, you know, an 8-page book. And I was fortunate in that the Elsteds [Crispen and Jan, proprietors of Barbarian Press] let me stay in one of the spare rooms while I was there, rather than commuting back and forth. It was the end of the day and I was sitting in their living room, I think we were having a cup of tea, and at that point they tell me I really need to get my own press. So, okay, I guess I'm doing alright.

Most of the time I look back on it and think that it was half luck, that I managed to get something that was fairly evenly inked and a decent impression. I think that press I was using was very good. But it was also giving me the confidence that I was actually doing something well. The press I learned on was a Super Royal Albion hand press from 1860 something. And that's a beautiful thing. The lever on it requires you to reach across and it's full body heaving to get it to press down. And that's kind of when I fell in love with doing it.

It's a big leap, though, to go from getting encouraging words at a four-day course to starting your own press.

It was still at least two years before things were going to get going. In that time I also took more courses. I did workshops at Emily Carr, through their book arts program that they had running for continuing studies. I did an introductory course to bookbinding, which looked at several styles, the last one being your typical flat back, hard back binding and that one was taught by Simone Mynen, whom I knew already because she had been one of the student in the (Barbarian) course as well, so I got to know her then. And then also I decided I wanted to have a grasp on all aspects of making books the way I wanted to and so I took the workshop in wood engraving that was being taught by Shin Minegishi and so from there I decided "Okay! I'm going to make a book."

How did you end up here, at Rasmussen Bindery?

It was 2007. I met Paulette, who owns Rasmussen, in the showroom of Lonsdale Leather. She was there buying leather. I was there buying leather. This was well before I moved in, and she had said, "When you're ready to set up come see me, maybe we'll have some space for you inside the bindery." Months later when I was ready and looking for a space I came to see and we talked about possibilities.

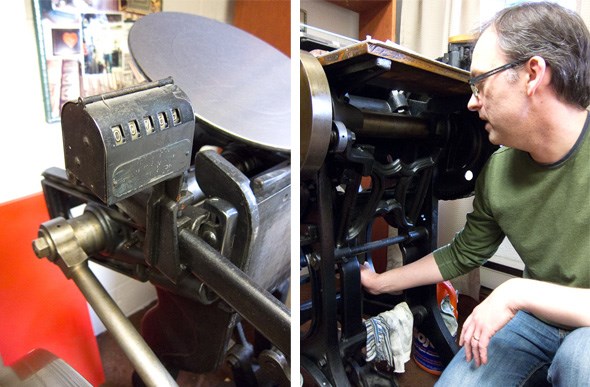

Morrison uses a 1910 Chandler and Price Old Style "jobber," named Beryl, which was originally suited for commercial applications such as creating a lot of stationery, notices, etc. He bought it for $400 from another Barbarian Press course alumnus, who was moving to Nelson and was just looking to recover the cost he had previously paid to twice move the 900 lb. cast iron press.

Morrison uses a 1910 Chandler and Price Old Style "jobber," named Beryl, which was originally suited for commercial applications such as creating a lot of stationery, notices, etc. He bought it for $400 from another Barbarian Press course alumnus, who was moving to Nelson and was just looking to recover the cost he had previously paid to twice move the 900 lb. cast iron press.

Did you give "Beryl" her name, or did her previous owner?

I was the one who named Beryl. I am of the opinion that every press has a character. Beryl is old-style, as I described to you. I thought she should have a name that was more common at the time she was made (1910) but one which had fallen out of use. It just fits her time when she was young and fresh. If I had an iron hand-press, I'd likely call her Prudence.

How long did it take you to produce The Importance of Being Earnest?

Two years, from beginning to end. I started it after the first Wayzgoose I was at, which was the Fall of 2007. I had one broadside which was sort of complete, only because I had it on show and I was taking orders, but I was still struggling with getting a good impression off of an illustration block because I hadn't done one before. Not with a press like this. But I managed to have something and I was able to get some feedback from other people, most notable from Jim Rimmer.

I think all roads lead back to Jim Rimmer, right?

I've heard him referred to as the Godfather of letterpress printing in Vancouver.

How did you choose The Importance of Being Earnest as your first book?

There were a couple of things. I wanted to have something which was recognizable, that a number of people enjoyed. Hopefully that didn't have the fine press treatment already. I think it was mentioned in Review that it was the first time in a long, long time that anybody had done a treatment of Wilde's, well it is touted as his best comedy, written at his height. I wanted something that was of a manageable length, but not too small. At the time I thought "100 pages, that's small."

I should note that in those two years I was not working at it every day. There were breaks in the summer time when I helped with binding here (at Rasmussen), and in 2009 when the book was finally out, we had had our first child in March of that year. So there were several delays. Needing to work, needing to bring in more money, and so having to break off from just working straightforward on the book. And that's pretty much the way that things are still going. I've now actually been taken on by the bindery part-time, for a couple of days a week, so it helps me, it helps them because I was here anyway, and they've done a lot of training for me in book binding that I didn't know and I've learned a lot more about finishing and binding itself. For me it's some predictable income.

Do you have a core group of fans who buy everything?

There are some who are officially subscribers. So I'm up to a little more that half a dozen. And some who are avid collectors and one fellow runs a blog called Books & Vines. He writes about books and wine all day it seems. He's been a great fan and subscriber. He was very happy with the first book and so he signed up. He's also kept in regular contact with me, even if it's been a long time since I've actually put out anything or said anything to anybody about how things are going. And I love having that because it's both encouragement and a reminder to me that I have these commitments. People have given me money already for books, or they've agreed to buy a copy, and all I have to do is finish it. So it's very uplifting when you get that base.

So there are the official subscribers, and then you have other people that I think "Why aren't you a subscriber?" because they are buying everything but in some cases it's institutions and they can't necessarily promise it, or they just always operate as "Tell us when it's out. We'll buy it then."

What is the benefit of having subscribers?

The deal is that they agree to purchase one copy of everything I produce, aside from if I do any jobbing work, and in exchange for a price reduction of 30% below the list price. So Earnest sells for $300 and subscribers pay $210. It's a very good way for them to save on building their library. For me, even though it's less income, it's the assurance that a copy is sold.

Morrison is currently at the binding stage of the Swift pamphlet. In this 1729 essay, with the full title A Modest Proposal for Preventing the Children of Poor People in Ireland From Being a Burden on Their Parents or Country, and for Making Them Beneficial to the Public, Swift suggests that impoverished Irish parents sell their children as food for rich gentlemen and ladies, which leads one to wonder about Morrison's sense of humour.

How do you decide what you want to do?

It usually proceeds from some inspiration or experience. With deciding to do Swift I actually wanted to do it within the first year that my first daughter Eleanor was with us. Prior to her birth my wife and I had been listening to the BBC and there was this panel discussion about Swift's A Modest Proposal. And we thought "Oh, wouldn't this be a fun thing to do." And it usually starts as something like that. And then when you revisit it and read it you say, "Yes, I'd like to do this." And I think it's almost a definition of private press that you're really just doing what inspires you. It may be what inspires the first thought, the first consideration of doing, but as you explore it, examine it, is it something I can do, does it fit the scope of work that I want to focus on. Will people buy it?

I think with doing Swift, it proceeded from that experience of listening to the panel discussion and all this time leading up to Eleanor's birth my wife and I would joke about eating the baby. We do have a dark sense of humour.

When you are thinking of the source material you want to work with, do ideas for the illustrations come to you right away?

No, I tend to need a little more time to sit with the texts. One of the difficulties in choosing material that has been done in some form of theatrical performance is making sure you're far enough removed from someone else's vision of what the story would looked like.

Earnest was influenced by the most recent film production with Rupert Evert and Colin Firth. There were certain things in that film I enjoyed, in particular the fight over the muffins, and so I decided I would portray the struggle scene at the opening of Act 3, the struggle over the last muffin. And originally I had designed an illustration that would be from the opposite perspective, that would be Cecily and Gwendolen in the foreground and the struggle for the muffin happening way back there, but then I decided "No, let's flip this and really bring the action up close." And so the struggle was happening right in front of your eyes. Because in terms of the action going on in that scene, the ladies are essentially more passive, because they are the onlookers. If you're going to have the action, have it right up front where everyone can see it. It just creates a more dynamic image.

And when I mentioned (A Modest Proposal) to other people, they wondered, "What will the illustrations look like?" And I'm in that right now, sorting those out, and I think it's more effective to play with people's imaginations than to, in this case, create some kind of gory image.

The approach I take with my illustrations is that it's a bit more commentary. With Earnest I didn't necessarily want to focus on the main action, so I just try to take a humorous approach to some of the side elements. The idea of Jack being a parcel, like one of Lady Bracknell's lines how she doesn't want her daughter to marry into a cloakroom and be wedded to a parcel. And so I thought "Fine. Wouldn't this look funny if Jack were wrapped up like a parcel."

Jarrett Morrison in his creative corner at Rasmussen Bindery. (top right) The illustration for The Bowler Press's first broadsheet "Chesterton Cheese." (bottom right) A detail from Captain Wentworth's letter.

With A Modest Proposal what I've been looking at for the illustration is really to explore the idea of a new economy around infants' flesh being marketed and consumed, locally. And some of the ideas that wind up coming out in terms of the economical and social consideration, it's really interesting. Because for all intents and purposes this fellow proposing this idea, one of the things he talks about is really just buying the local product. Eat locally. So it conjures up visions of "What would this look like?" or the idea of married women competing to see who could bring the fattest child to market. What would that look like? Would there be a line of women waiting to drop off their child, to be paid and they're going to get weighed? What would that look like? Would everything function in this kind of order, because if you can just go and sell, would the people who are going to keep their child then have to worry about their babe being stolen and sold? It becomes a precious commodity for economic gain.

So it's all these things. And there are several things described so I'm trying to integrate them all together into a cityscape. So you can look in one corner and see this kind of thing going on and look in another corner and see something else. And I'm trying to create enough things. Fortunately with wood engraving you can get pretty dense in terms of the number of things going on and the number of details. I want to see how much I can pack in.

It seems that there are two "camps" of letterpress print makers: Those that create books and other items to be read, and those who create them to be only looked at. Where do you see yourself?

It is my hope that people read the works I print. So much of the design process involves spending a great deal of time with the text, letting it inspire me, guide me in the creation of the format. Tactile elements – the feel of the paper and binding in the fingers – are integral. I agonize over the way one moves through the text, doing my best to delight in the act of reading, but without distracting from the text itself. So many details are intended: the typeface, the point size, the line measure, number of lines, rag margins or justified text, placement of the illustrations, the resulting thickness and heft of the book; all for the reading experience.

It's a strange dichotomy. As printers and designers of books, we attempt to operate by stealth, at least typographically speaking, to create a comfortable current for the reader, let the reader flow with the text, and not notice we are at work guiding that interaction with the text. At the same time, we want to be stunning in our presentation, for the reader to marvel at our prowess, our daring in designing a book that should look like it reads for the reader who loves the story.

Finally, where does the name "The Bowler Press" come from?

It's not that significant. I have a Bowler hat that I bought from Roberta's Hats in Victoria. And I was looking for an imprint that didn't really have to mean a lot but rather spoke more to the era of the equipment that I'm using and what I'm doing. Kind of a trades person, it would more of less be my station. It was actually Caroline that suggested it and I thought "Okay. That'll work."

Photos by liisa hannus and courtesy of Jarrett Morrison.