The NHL has gone through numerous changes in over a century of existence.

Rules have changed to allow forward passing and let goaltenders drop to the ice to make saves. Equipment has changed — sticks now have curved blades and are made of a composite of high-tech carbon fibre and resin. The rink has changed — lines and faceoff dots have been added and removed, the goal crease has grown and shrunk, and plexiglass has replaced chain link fencing above the boards.One thing that hasn’t changed, however, is the puck. The basic elements of a hockey puck haven’t changed much since the early 1900’s — a flat, black disc of chilled, vulcanized rubber — though minor improvements and standardizations have occurred over the past 100 years.

The black hockey puck is an iconic part of hockey but multiple times in NHL history, they considered changing the colour of the puck to orange.

Art Ross’s orange puck

The idea was first suggested way back in 1949, three years before the first broadcast of an NHL game on television. It wasn’t just a whimsical suggestion — the person advocating for orange pucks was Boston Bruins general manager Art Ross.

Ross was an innovator, constantly looking for ways to improve the game. He came up with a new goal design — a B-shaped net that resulted in fewer pucks bouncing out of the net when they went it, making it easier to tell when a goal had been scored. That design lasted well into the 1980’s and is still familiar with kids today who play tabletop hockey.

One of Ross’s innovations was an improved puck, with a bevelled edge and a standardized synthetic rubber construction in the 1940’s that led to less bounce and more consistent performance. But Ross wasn’t done.

Ross was concerned about the visibility of the puck, particularly when it was in the air. So, arms full of pucks with orange-coloured designs, Ross went to the NHL’s annual meeting in 1949 to argue for a more brightly-coloured and visible puck.

The idea was rejected.

“A change from the black puck was considered too experimental for immediate consideration,” reads a Canadian Press report from W.R. Wheatley on June 9, 1949.Another report from the Montreal Daily Star says that Bill Tobin, then the owner of the Chicago Black Hawks, had already tried an orange puck in Chicago and it “didn’t work.”

That same annual meeting also included a note about television: “There was a feeling that hockey is too fast for proper display and for following of the puck on television.”

That same reasoning would lead to renewed calls for an orange puck about a decade later.

Tracking the puck on television

The first television broadcast of an NHL game was a french-language broadcast on CBC of a game between the Montreal Canadiens and Detroit Red Wings on October 11, 1952. Only the third period was broadcast for fear of losing ticket sales for the game.As the decade progressed, more and more games were televised and there was a growing concern that the little black puck was simply too hard to see on television. It was too easy to lose the puck amidst the other dark colours on the black-and-white sets.

In 1957, the NHL rules committee actually approved a suggestion to add an orange stripe on the puck to make it easier to see on TV — “one quarter of an inch wide around the circumference or side of the puck.” The idea evidently died before the puck hit the ice, however.

In 1959, according to a report in the South Bend Tribune, the Amateur Hockey Assn. of the United States and Canadian Amateur Hockey Assn. proposed that the NHL add orange stripes around the edge of the puck to increase its visibility. They also suggested that yellow hockey tape be used on sticks instead of black, making it easier to see when the puck was on someone’s stick.

It was an idea the NHL seriously considered. When the New York Rangers and Boston Bruins went on an exhibition tour in Europe, they brought along 288 orange pucks to test out. They were not popular.

“We paid all that excess weight charges on those dizzy things and they were a pure flop,” said Rangers general manager Muzz Patrick in a report from the Detroit Free Press. “The players said they couldn’t see the puck and wouldn’t use them after the first try. European teams are going to use them, however, because we gave them away for free.”Ironically, the attempt to make the puck more visible on television wound up making it harder to see on the ice.

WHA tries to set itself apart with orange pucksIn 1972, the World Hockey Association rose up to challenge the supremacy of the NHL. They offered higher salaries than the NHL to lure players to their new league and introduced sudden death overtime to limit ties that disappointed so many fans.

One way the WHA attempted to set themselves apart from the NHL was with — you guessed it — orange pucks.The WHA had their teams play scrimmages at training camp and preseason games with the orange pucks, with one theory that the more visible puck would be used to help the fledgling league get a television contract. There was just one issue: the orange pucks were awful.Whatever process was used to make the pucks orange also affected their durability. As a result, pucks would get deformed during play — flattening on one side if they hit the boards too hard or breaking apart when a hard shot rang the post.

Another issue was that the orange puck was often harder for goaltenders to see, particularly at the home of the Ottawa Nationals — their home rink at the Ottawa Civics Centre had orange seats. So, the orange pucks were abandoned.

The WHA ultimately settled on a dark blue puck, which wasn’t far off from the NHL’s black puck, but they weren’t done experimenting with brighter colours. They tried a bright red puck during the 1974 preseason, but it was never used in a regular season game.The dream of an orange puck in the 80's and 90's

In the 80’s and 90’s, there were still concerns about being able to track the puck on television. Before the days of high definition, the puck could be easily lost on the screen, making it particularly tough for new viewers to follow the game. With the NHL expanding to southern U.S. markets in the 90’s, this was a particular concern.

In 1982, efforts were again made to get the NHL to consider orange pucks that would be more visible. According to a report from the Chicago Tribune, the Black Hawks used orange pucks during practices in the 1981-82 season and they weren’t the only ones, as teams were anticipating the NHL would introduce orange pucks in the 1982 preseason.

“Fans always say they can’t see the puck,” said Don Murphy, the Black Hawks’ public relations director. “They’ll see these.”The 1982 preseason came, however, and the orange pucks never materialized. According to a December 5 report in New York’s Daily News, the “orange pigment kept turning rubber a maroon colour.”

Still, with the NHL expanding to Tampa Bay, San Jose, Anaheim, and Sunrise in the early 90’s, the pressure to improve the television broadcast and make the puck more visible was a constant concern, with orange pucks brought up again in 1991 and 1992. The NHL wanted a lucrative television contract but the tiny black puck was a problem.

“The problem with hockey,” said NBC producer Glenn Adamo in a 1991 Chicago Tribune article, “is you have a black puck that is only about three inches by an inch that’s on white ice. And the problem with television is you can’t have 100 percent or more white saturation or the colours start to sing and hum — literally.”According to a 1992 report from Thomas Boswell in the Daily Oklahoman, one experiment with orange pucks on television made them look like “an orange comet with an unattractive teardrop effect.” But he quoted NHL vice president of broadcasting Joel Nixon as saying, “High-resolution TV is coming. Maybe it’s time to look at things again, even orange pucks.”

In 1993, however, new NHL commissioner Gary Bettman nixed the idea of orange pucks entirely: “I’m never going to advocate orange pucks or other crazy ideas.”

Orange pucks and other crazy ideas

As much as Bettman suggested the dream of an orange puck was dead, it wasn’t entirely.

1993 saw the introduction of the Firepuck — a puck with embedded retroreflective materials that, in combination with a spotlight, caused the puck to glow on television. The Firepuck was demonstrated during the 1993 NHL All-Star Game, which showed clips from the puck being used during a Minnesota North Stars practice.The Firepuck was later experimented with by the IHL, though never widely adopted. Pictures of the experimental puck show that it was, indeed, very orange.A few years later, Fox acquired the rights for the NHL and introduced their own variation on making a puck more visible on a television broadcast: FoxTrax.While the FoxTrax puck wasn’t an orange puck like Art Ross had dreamed of, it accomplished a similar effect as the 1982 experiment with orange pucks on television: a comet on the screen with a teardrop effect.The augmented reality glowing puck was introduced at the 1996 NHL All-Star Game and lasted until the end of the 1997-98 season, when the NHL broadcast rights returned to ABC.

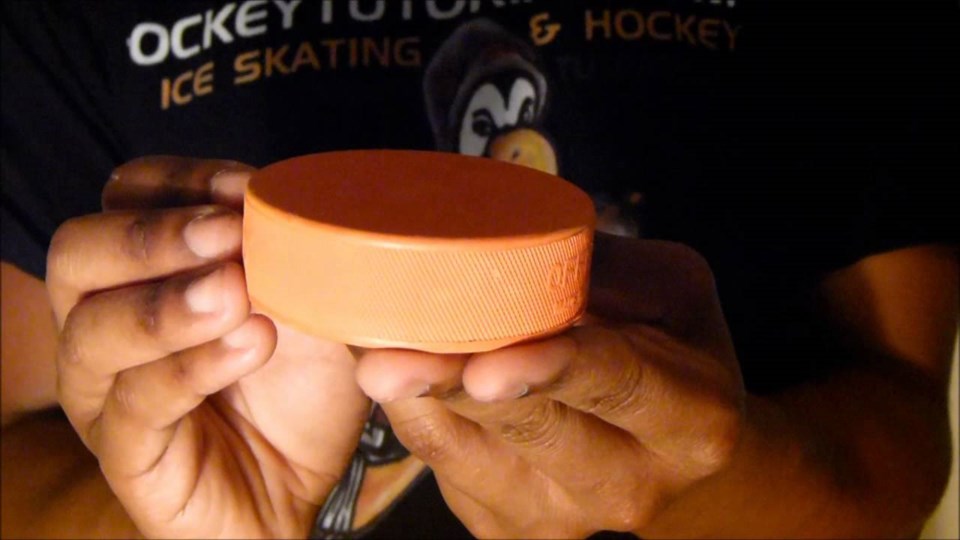

These days, there are plenty of orange pucks around. Hollow plastic ones are frequently used for floor hockey, hard plastic pucks with nylon gliders are used for street hockey or inline hockey, and an orange puck on the ice typically means that it’s a heavier, weighted puck for use in training to increase stickhandling speed.It’s unlikely the NHL will ever consider orange pucks again, as the advent of high-definition television means the little black puck is easier to see than ever. But it’s amazing to think that if it had been introduced to the NHL back in 1949 the way Art Ross wanted, an orange puck would be part of the tradition of the game.