By Michael White

It may feel as though the privilege of dining out has been with us forever, but the variety and plenitude of restaurants we 21st-century urbanites experience as a mundane fixture of everyday life would have shocked forebears as recent as our great-grandparents.

And make no mistake, it is a privilege.

The hundreds of thousands of restaurants that dot the North American landscape some of them extraordinary, most of them average, too many indistinguishable from their global franchise counterparts are an unprecedented byproduct of a population whose demand for choice and convenience can seemingly never be satisfied.

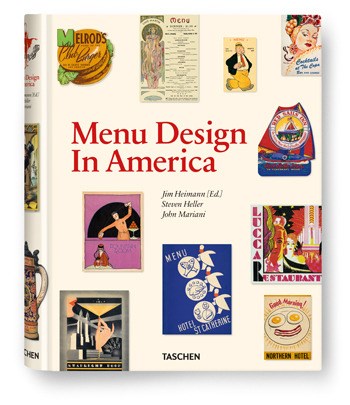

Of course, eating in a restaurant is about much more than consuming food for survival. Its entertainment, a ritual, a way to kill time or make the most of it. And if every restaurant meal is a story that can later be retold, its most important opening detail is the reading of a menu. In that spirit, Menu Design in America, 1850-1985 (Taschen, $60), although an art book first and foremost, offers a microcosm of Western social history during the past century and a half. Featuring almost 800 menu covers and interiors, it spans the gamut from a formal dinner honouring President Abraham Lincoln in 1861 to a Los Angeles drive-in circa 1933 (steak with salad, shoestring potatoes and a bun; yours for 50 cents) to illustrated cocktail lists from the countless Polynesian-themed lounges that sprang up in the 50s and 60s.

Steven Heller, a prolific design-book author who co-edited Menu Design (with Jim Heimann and John Mariani) explains that the origins of the menu are vague other than that they undoubtedly are French. Initially, restaurants were rare (most people couldnt afford them) and among those, menus were rarer. More often that not, everyone would eat the same thing as determined by what the kitchen had on hand. For a long time, menus were strictly utilitarian, a means of communicating what was available. Today, menus fulfill multiple purposes: to stoke the appetite, to make suggestions and to reinforce brand identity. Former New York Times restaurant critic Frank Bruni described the modern menu as a kind of gastronomic cheerleading.

We see that evolution throughout this book, as indelible logos, design motifs and mascots and evermore-florid descriptions become increasingly common. We also see how some restaurateurs have unintentionally provided souvenirs of American culture at its most pitiful: witness the blackface logo of a Seattle chain called Coon-Chicken Inn.

Above all, Menu Design shows that there are as many ways to present a bill of fare as there are things to eat. Whether leisurely five-star dining or cheeseburgers served through a window, there has long been a subtle but sophisticated craft to attracting the hungry masses in those crucial moments before money is exchanged and the appetite is sated. This is a must for anyone interested in commercial art and one of the most accessible, something-for-everyone coffee-table tomes of recent years. Menu Design in America is, quite simply, a visual feast.