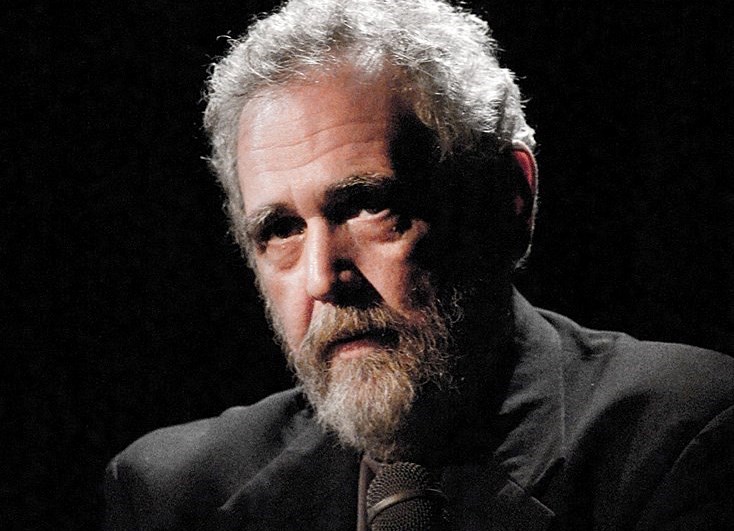

If you can count John Oliver’s Last Week Tonight, Real Time with Bill Maher, or any incarnation of The Daily Show among your television viewing habits, then you should lend an ear to Barry Crimmins.

A politically menacing party of one (many say he originated the truth-telling style of comedy so popular now), Crimmins began his career shouting out the hypocrisy and foolishness of government from the rooftops. His anger – virulent and, at the time, of somewhat mysterious origin – was unnerving. (To this day, he counts two goals in life: overthrowing the US government, and dismantling the Catholic Church.) And, as chronicled in the moving documentary Call Me Lucky, it alienated as many as it inspired as he spearheaded the Boston-area underground comedy scene in the hard-living ’80s.

Then, in the mid-’90s, Crimmins made a dramatic detour from the comedy spotlight into US Supreme Court as an advocate against online child pornography – a subject so personal and traumatic (Crimmins publicly revealed in the early ’90s that he was raped several times as a child) that he says being its spokesperson nearly destroyed him.

As he waged his crusade – and almost single-handedly changed how the law dealt with these heinous crimes – time slowly overwrote Crimmins’ name in the popular consciousness and replaced it with today’s satirical offspring. Amongst comedians of a certain ilk, however, it has lived on, and, now, his confrontational style of political commentary seems more relevant than ever (be sure to check out his recent Louis CK-produced special, Whatever Threatens You).

We caught up with the comedian by phone at his rural homestead in upstate New York, prior to his appearance in Vancouver next week as part of the JFL NorthWest comedy festival. At the time of our interview, he was just recovering from a fresh trauma: being hit by a truck en route to a gig.

I understand you had a terrible accident. How are you feeling?

Crimmins: That’s a long story. It could take up a lot of the interview. [Laughs] But yeah, I’m alive. We’re alive. That’s the main thing.

Now we have to live. That’s the hard part.

How was your experience with the hospital?

Terrible! It’s the United States. We have a couple of things going on here that are ridiculous. I mean, I’m the passenger in the back seat of a car and they’re asking me for my auto insurance. It’s just like… I’m sorry, I didn’t realize I needed to be a licenced, insured driver to ride in the back seat of a car. You know? I didn’t realize that.

Everything is cross referenced, and somehow they’ll end up charging me more money, for being hit by a truck. I didn’t have a lot to do with it except I got in the car, like I have a million other times, as a performer who gets taken from one place to another. [...] Personal responsibility is very important, but self-scapegoating is a serious mistake to make. I didn’t do anything wrong. I got hit by a truck. [Laughs]

Speaking of personal responsibility, what do you do with a president who denies that true things even happened?

We just had a pretty good census of how many truly self-loathing people there are in the United States. You know?

“Hate yourself?”

“Yes, I do.”

So, now there’s Donald Trump. Well, it’s about time we had someone who hates us as much as we hate ourselves as the president. That’s what we have. He’s the abusive patriarch of the country.

And people, even when something’s horrible, they have comfort zones. So, really, rather than be kind to victims [...] it’s easier to just cover up for the one perpetrator. That’s how incestuous families work. That’s how horrid work places [function]. They cover up for the serial bullies. We take care of the serial bullies and form lynch mobs for the victims.

So it’s less that he’s a mirror of the American voter, and more that he’s the bully they’ve been waiting for?

Right. And if the bully likes you, that’s even easier.

When someone like Donald Trump comes into power, do your comedy chops start salivating? Or do you ever grow weary of the grind?

No, no, not at all. My friend Eddie Pepitone says anybody who’s not in show business is a coward. Because anyone who’s ever seen it thinks in terms of it. Thinks what they would do. So the first thing people think about is what would I do if I got on stage, what would I use for material? And then they get kind of desperate: What do I have to say?

Well, I’ve had a lot to say for a long time. I have a lot of ideas and takes on a lot of things, and to just try to turn it into something cohesive and loving and of some value to people, and figure out the proper sequencing of it, is everything. Thinking of the little jokes, I mean my brain already thinks in humour, and it’s a way to smuggle content and ideas to people, and they drop their guard a little bit.

It’s not that all humour is truthful, but the truthful stuff, really, is the best.

Do you see comedy as a means of social change?

It’s certainly a means to social change. My dear friend and mentor, the late Howard Zinn... it was a rare time that I spent with him that he didn’t tell me how important it was to do this kind of work. And he would just say, you are so much more effective than three hours of boring speakers with all sorts of gravitas. You connect. And if you tell them the truth, and they laugh, you’ve made the connection and you know that you’ve given them something.

The other really important thing is that it shows people that it can be fun to stand up to injustice and oppression and greed and abject stupidity.

What will you be bringing to your show in Vancouver?

I got a new piece that I will at least be doing a chunk of up there called Atlas’s Knees.

What does that name mean?

When I disclosed in print that I had survived rapes as a young boy, that’s when, anecdotally, I began to collect the world’s largest collection of anecdotal information about child abuse. Because everyone comes to you. Then, I did a piece about child pornography that got a lot of notice back in the ’90s, so I started to hear from a lot more people and got asked to comment on a lot of things. And you know, I kind of ended up in a bit of a role of – I don’t like the word leader, because leader implies you’re a moron. It sounds like you’re on a field trip, you know? Like, I know how to go to the museum on my own. [Laughs] But I’ve sort of been on the forefront of what I would call the children’s rights and safety movement, which is the world’s most overdue and necessary human rights initiative. And we’re still in the nascent stages of it.

As I kept collecting people’s [stories], I’ve been telling people forever that children, to make sense of the world, someone has to tell them that what happened to them is wrong: You were innocent and this shouldn’t have happened to you. Instead, generally nobody says anything, so the kid is thinking they did something wrong. Eventually that turns into: There’s something wrong with me. And the self-loathing and self-destructive behaviour to corroborate the self-loathing can come along.

So, when everyone kept coming to me, what happened is my self-loathing kicked in, in the sense that I apparently decided I didn’t deserve to be healed until everyone in the world was going to be healed. Which means I was never going to be healed. [...]

And then, in the movie [Call Me Lucky], we encouraged people to talk about what happened to them [...] and a lot of people interpretted that as, they should talk to me. So, basically until about last week, for 23 years, I had been running a one-man rape crisis centre 24 hours a day, seven days a week. I had so many worlds full of demons that I was carrying around, and it was catching up with me. I started having flashbacks. I couldn’t do it any more.

When I did the child pornography investigation and blew the whistle on that in 1995, that’s a lot more than most people ever do, and I put in another 22 years after that. Then, with the big push after Call Me Lucky, I realized I just couldn’t do it anymore. I had done enough.

So, I felt really free and happy for the first time in years... And then I got hit by an 18-wheeler four days later.

• You can catch Barry Crimmins Feb. 23 at the Biltmore Cabaret. Tickets and info at JFLNorthWest.com. This interview has been edited and condensed.