As you stand in the lobby of the Rosewood Hotel Georgia one particular painting appears to move – its Venetian canals simultaneously advancing and retreating as your body shifts around to make sense of it. And no matter how many times you figure it out – see the three-dimensional magic at work – it still happens.

Created by English artist Patrick Hughes, this mind-bending seascape (painted on wood blocks so as to protrude off the wall) is the product of more than 50 years of exploration into how the human mind perceives image and illusion.

In this, his 75th year of life, and on the heels of receiving an honorary doctorate for his contributions to neuroscience, the Winsor Gallery in Vancouver presents The Hues of Hughes: Selected Works 1999-2014, running now until Feb. 24. Alongside the op-art exhibition will be videos, interviews, and documentaries on Hughes and his ground-breaking “reverspectives.”

Westender caught up with Hughes in London for a spirited chat about receding lines and the railway track of life:

How do you decide on these scenes you end up painting?

There’s two parts of it: one is the geometry, one is the imagery. In the case of Venice, there are 10,000 buildings I can use, whereas, when I do an Andy Warhol picture, there are only about 10 good Andy Warhols that I would do.

They're all the same height as well – four or five storeys high – so there's variety but similarity. And also, in the case of Venice, since it's situated in the lagoon, you paint the water at the bottom and it moves very well.

And oddly enough, it’s because it’s a given thing, Venice. Everybody knows it. It’s a cliché, in a sense. You could say it's the most beautiful city in the world, isn't it? I've painted rainbows before. Rainbows are one of the most beautiful sights in the world. It’s these given things that you can interfere with.

Do you paint from life?

I often go to Venice but I've never drawn it from life. I've mostly bought books of photographs and taken photographs myself. Photography and indeed the computer are very useful to me. What you can do is photograph a building head-on and in the computer make it into perspective.

Ah, so you've incorporated the computer into your painting process?

Oh very much so. It doesn't look like computer art, but I couldn't have done Venice without a computer. That picture in the [Rosewood] Hotel Georgia maybe took half a year to draw and paint it; it took a long while. With the computer, in Photoshop, you can change things to the right size and shape in minutes.

Is a sense of familiarity necessary to a successful illusion. When people know instantly what they're looking at?

Yes, I think so. But other illusionists – Victor Vasarely [the grandfather of op art], Bridget Reilly, Agam – they did abstract illusions. But I find it better to do figurative illusions, myself. Another artist who did figurative illusions was [M.C.] Escher. Buildings and so on…

Why this technique?

Originally I just wanted to do the opposite. I always did things different. I thought, ‘Oh, I’ll make the perspective sticking out instead of going in.’ And then when I put it on the wall it receded again. One of the things it does is it sticks out but seems to recede. The second thing that it does is it seems to move. And then you come along and look at it, you put it back together again.

Your brain flips it a few times.

Yes, it changes. It’s odd… When we say ‘illusion’ it isn’t a visual illusion. When it’s just a photograph of it in a newspaper or a book it isn’t an illusion at all because it’s flat. It’s only an illusion when your body is moving. The overall feeling is one of reciprocity. It moves according to how you move, and in the opposite way.

Did it surprise you when you first discovered it?

Yes it did! It was 51 years ago. It used to be 50 years ago [laughs]… And one of the lucky things about it is it still surprises me, and it will still surprise you when you go to the hotel again. It will still do it. It’s the gift that keeps on giving.

Is Venice one of your most popular subjects?

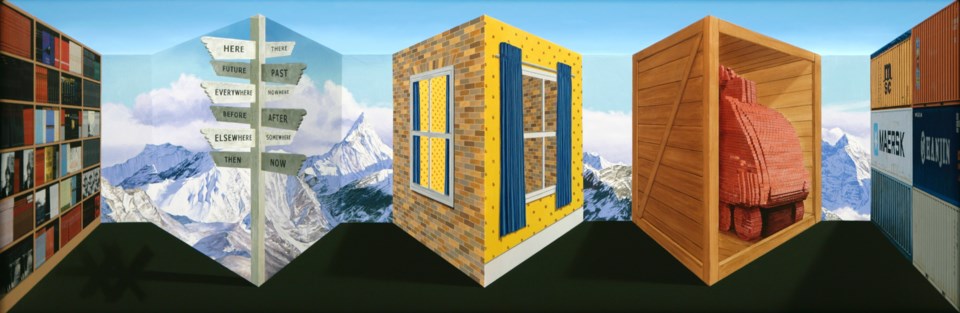

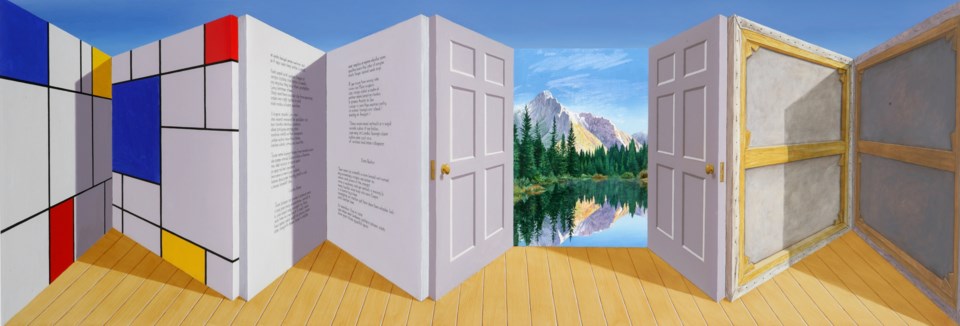

I’ve gotten lots of enjoyment out of doing doors, because they’re supposed to move. I try to look to do a variety of different shapes and pictures. Brillo boxes. Cameras. I’m always looking for something new to do.

Always looking for lines...

I’m always looking boxes or rooms, spaces or buildings. I’m not looking for fish, or snakes, or leaves. I’m not in the natural world, I’m in the man-made world, aren’t I? I’m a human being. I’m concerned with what we do, really.

Have you ever felt confined by your medium?

I love my straightjacket! The restrictions are very thrilling... Masochists love their chains. I love the geometry because it’s something you can fight against. People erect their own constraints, don’t they? Like Samuel Beckett or Mondrian or an entire book without the letter ‘e’… I think the constraints are delightful.

It’s a strange discipline: geometry and symmetry and Euclidean things. I’m sitting in a room right now and it’s all lines and geometry, pictures on the wall… It’s rather comforting. [laughs] Something you can really rely on. I never thought about it when I was younger, but there’s something comforting about it all appending towards infinity – the way railway lines come to a point. An underlying logic.

Your paintings focus on humans and what we’ve built, but there are no humans in them…They’re barren.

Yes they’re sort of ideal, aren’t they... In the Renaissance, towards the end of the 15th century, there were three paintings of ideal cities and they were painted empty.

Sometimes people say, ‘Why don’t you have people in your pictures?’, and I say, in a smart aleck way, ‘Well, you’re the people in my pictures.’

In that one in the Hotel Georgia, you go into it in the way that you go into a home. There’s either nobody there or somebody you know very well. It would be very disconcerting if there was somebody else there! [laughs] You enter into the room and explore it yourself.

Did you ever feel like your art was in fact part of a scientific process?

Yes I did! I was recently, proudly given an honorary doctorate in science by the University of London and I am friendly with neurologists and psychologists of perception.

I’ve done some small Patrick Hugheses and people are looking at them with brain-scanning machines, studying what parts of the brain perceive movement or spatial depth. Which parts light up. So I have, for the first time ever, involved myself as providing experimental materials.

That milestone comes at an interesting point in your career.

Yeah, it’s good isn’t it. I’ll be dead soon but I’m making the most of it. [laughs] I’ve been lucky in that I’ve developed a lot in my 50s, 60, and 70s. It’s hard to have new ideas but I’m still having new ideas, new thoughts about what to paint and how to paint it. W

• The Hues of Hughes is at Winsor Gallery (258 East 1st) until Feb. 24.