Main Street is often referred to as the dividing line of the city – a physical marking of where the historical class politics of the wealthy western suburbs and the working class East Side met.

A modern epicentre of fashion, food, and factory culture, Main Street has also long-served as an intellectual corridor where many of the city’s artistic legacies took root – none more so, perhaps, than that of Western Front.

Founded in 1973, when the idea of artist-run spaces was just beginning to gain momentum in Canada, Western Front has since prevailed to become one of the oldest existing artist-run centres in the country.

The mandate was simple: provide a place for artists to exhibit work and engage with the community about it, and also provide resources for the creation of new work.

Over the years, the non-profit has served as a pivotal incubator in the local music, dance, and audio-visual scenes, and throwing fearlessly hardcore events, like the Voice Over Mind festival (which explores oddities of the human voice) that just wrapped last week.

Artists like General Idea, Allyson Clay, Joseph Beuys, Image Bank, and Paul Wong have all been exhibited, and, more recently, the work of Paul Chan, Hadley+Maxwell, and Elizabeth Zvonar. There’s also a long list of prominent artists, such as Stan Douglas, Ian Wallace, Laurie Anderson, Janet Cardiff and George Bures Miller, Paul Chan, Jimmie Durham, William Burroughs, Vede Hille, and Young Marble Giants, who have come through its doors.

It happens at night

Historically, Western Front was riding the wave of collaborative art in Vancouver. Its creation coincided with the end of Vancouver’s influential Intermedia arts collective the year prior, but this was actually a sign of the growing scene, with the hundreds of artists involved in that movement splitting into different interest groups.

According to the Centre for Canadian Contemporary Art, many of Western Front’s eight founding artists (Martin Bartlett, Kate Craig, Henry Greenhow, Glenn Lewis, Eric Metcalfe, Michael Morris, Mo van Nostrand, and Vincent Trasov) had ties to Intermedia, which led to Western Front stepping into a crucial role in the “art ecology” of Vancouver.

From free jazz nights to the Fluxus anti-art movement, the space was interdisciplinary before the term became the beat writer’s catch-all.

“Western Front is a really supportive space for experimental thinking and looking at things that aren’t necessarily fixed,” says exhibitions curator Pablo de Ocampo. “We’re not just taking pictures off an artist’s wall and putting them up in a gallery.”

Instead, they’re more likely to put those pieces in dialogue with each other, other media, and broader themes.

De Ocampo, who joined the organization by way of Toronto just nine months ago, has taken on the difficult role of honouring the space’s diverse artistic record without getting too caught up in its history.

To stay relevant, de Ocampo says he looks outside the archives, and even Vancouver, for inspiration.

“There’s something that’s really important about the history of this community and the history of this type of artist practice, but we’re not going to get anywhere if we just sit in a circle and all look backward,” he says with a laugh. “It’s important to invest in new artists and new voices, and do research to bring new ideas and new elements into the fold.”

From ‘Freak Hall’ to family room

Western Front is now a nationally-recognized leader in the creation of new art, however, many people don’t even realize that it’s a public space.

Tucked just off Main in a somewhat intimidating two-storey wooden building (that once served as the meeting hall for the Knights of Pythias), de Ocampo admits that having played home to a fraternal secret society doesn’t lend itself to having an inviting facade. According to de Ocampo, even some long-time neighbors weren’t sure what went on inside. (Which is probably for the best: after Western Front purchased the building, an undated newspaper article blared the humorous headline “Freak Hall To Open”.)

The artists initially purchased the building as a solution to Vancouver’s live/work-space shortage. Since then, elements of the building, such as the Grand Luxe Hall – a 120-person room used for screenings, concerts, and presentations – have remained relatively untouched, while areas like the communal dining room have gone through many transformations, from a gathering spot for artists, to the Lure of the Sea Bar, and, currently, as Front’s main gallery space. The building’s apartments are also still inhabited by founding members or early contributors to the space – a testament to Western Front’s legacy of stability and durability.

Between the lines

This month (running until May 2), the gallery hosts Reading the Line, an exhibition of five artists for whom line is an integral part of their work.

“The idea was to think about line as something that’s both a visual element and something that carries a story, or carries information, or carries history,” says de Ocampo.

Ontario collage artist Maggie Groat explores this with a meticulously-stitched quilt and a collage of photographs; Berlin-based artist Alma Alloro blends traditional craft mediums and digital culture with a piece made out of animated GIFs; while Toronto movement and video artist Tanya Lukin Linklater contributed drawings and a collaborative dance performance on opening night last week.

And central to the exhibition are three large sculptural pieces by local cloth weaver Anne Low.

A traditional hand-weaver, de Ocampo explains, Low’s approach to textile art is to make something that is “a blanket, but also about a blanket.”

Her pieces are used in combination with other structural elements to create a commentary on the piece itself.

Contrasting these contemporary works with something more historical, the exhibition also features drawings, notebook sketches and compositional elements from the 1975 film Light Music by British artist Lis Rhodes.

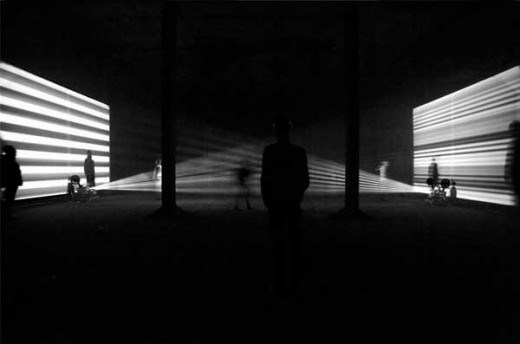

Viewed as two projections, Light Music is Rhodes’s commentary on the perceived dismissal of female composers in 20th century music. To do this, she created a “score” of drawings that create patterns of black and white lines onscreen.

A rare, one-night screening of the iconic 16mm film will take place in the Grand Luxe Hall on Thursday, April 9 at 8pm.

“In both Anne’s and Lis’ case, they’re artists who are making very beautiful visual structures,” says de Ocampo. “But, in Anne’s case, there’s this dialogue with the history of craft and what it means to make something by hand in 2015, what it means to be in dialogue with this history of labour, of women’s work, and thinking about the decline of handmade textiles as the industrial revolution came to be.

“And in Lis’ case,” he continues, “she’s an artist who was using the line to think about her position in the early ‘70s in London, England, as one of the few women who were part of an avant-garde film community there at that time. So her work, again, has this sort of invisible narrative that runs parallel to the visuals that you see.”