In Miltons epic poem Paradise Lost, Adam and Eves nakedness is initially as natural as the lush beauty of the Garden of Eden. Then Eve goes against Gods command and bites into the apple from the Tree of Knowledge. Suddenly, Adam and Eve look at each others nakedness differently. They lust after one another, have sex, and awake to the knowledge that there is good and evil in this world. The burden of having to choose between the two has been mankinds to bear ever since.

For centuries, Westerners portrayed the South Pacific as a Garden of Eden, where demure bare-breasted women pluck flowers to put behind their ear sexual but in an innocent sort of way. The men are all noble savages, strong and brave even as the onslaught of modernity reveals their powerlessness.

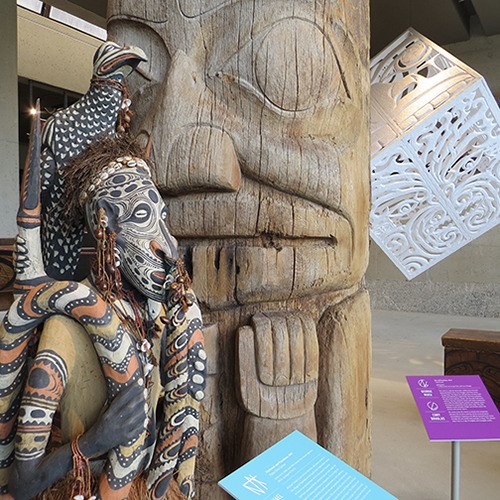

An exhibit at the Museum of Anthropology challenges those stereoptypes. It asks whether the South Pacific ever was a paradise and, if it was, whether that paradise has since been lost to such things as ecological degradation and the cultural pressures that go with it.

The Pacific is a complicated place; its not what you think, says Carol Mayer, curator of Paradise Lost?, a collection of 28 works by 13 artists dotted throughout the MOA until September 29. (There are also works on display at the Satellite Gallery, 560 Seymour, until August 31.)

The exhibit was born out of the 2013 Pacific Arts Associations international symposium, which MOA hosted in early August. Since there was already a major art exhibition at the museum (Safar/Voyage), Mayer decided to intersperse the contemporary art pieces throughout the existing displays.

One-third of the world is touched by the Pacific Ocean yet, given how small some of the islands are, and how far apart they are from one another, its hard for us to know much about the people at the other end of our horizon.

Mayer showcases sometimes for the first time in North America work by artists from Papua New Guinea, Aotearoa (New Zealand), the Republic of Vanuatu and Samoa.

Sometimes they want to challenge our perceptions. Sometimes they want to sound the warning bell, letting the world know whats really happening. However, what each artist seems to be asking for is our understanding. Since weve all bitten from the apple, they want us to embrace knowledge by getting to know more about their culture, good and bad.

One of the most telling paintings is by David Ambong, who was born on an island in Vanuatu, described by some as the happiest place on earth.

One of the most telling paintings is by David Ambong, who was born on an island in Vanuatu, described by some as the happiest place on earth.

Centuries of colonization ended in 1980; the idea was to return the land to the original owners, but no one can agree who those owners are, even among the islands families.

Land Disputing in Port Vila, 2010, shows a cool-as-a-cucumber white man walking away from two fighting brothers, one of whom is clutching a bag of gold coins. The brother with the gold coins the modern-day equivalent of Satans apple wants to cash in on the tourism potential and, like the white man, doesnt care that the islands beauty will have to be destroyed to make room for the hotels. The other brother says it isnt his land to sell.

The question mark in exhibits title is telling: the answers always lead to more questions; were even told to question our questions.