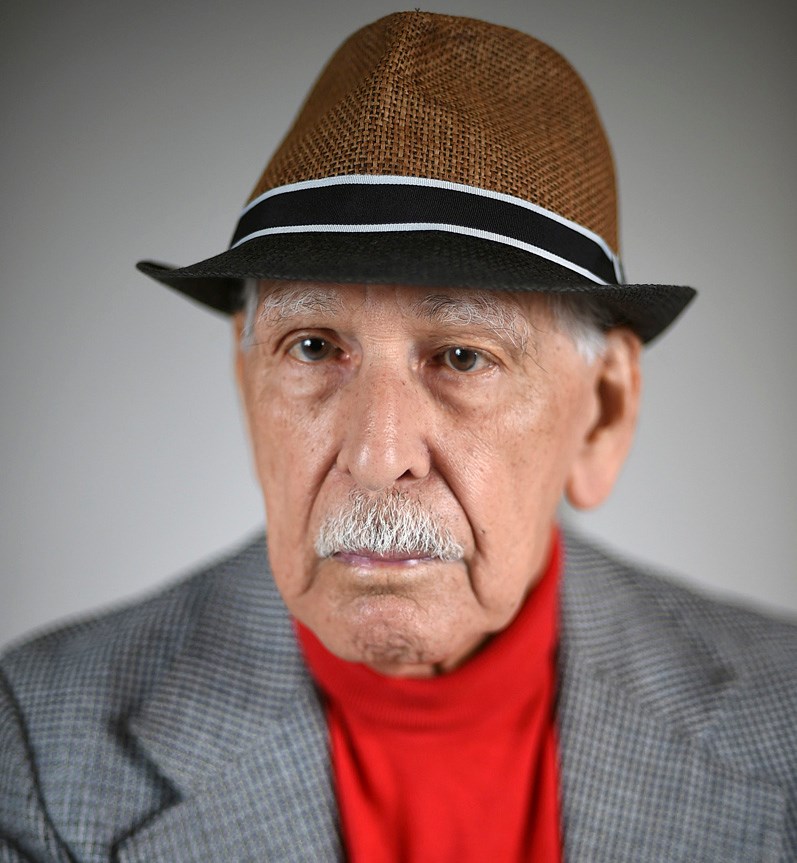

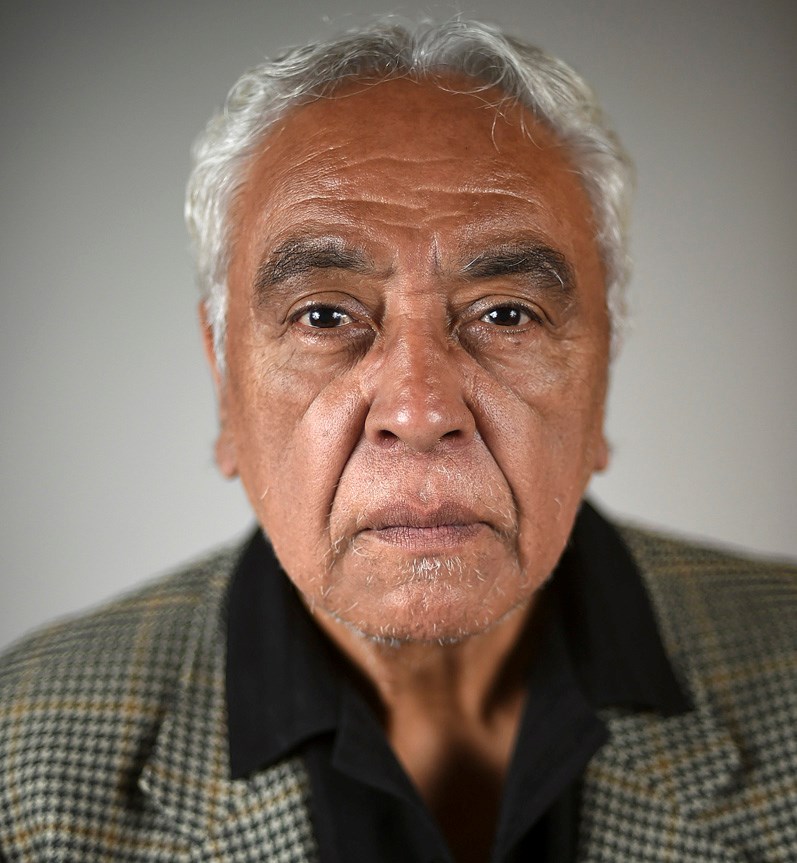

Bill Lightbown has seen a lot of life.

The best of it and worst of it.

That ebb and flow is inevitable when a person is born in 1927 and survives long enough to know what it’s like to be 89 years old and live in an apartment near Commercial Drive.

Sometimes, as Lightbown discovered when he was a young man, the worst parts of life can unexpectedly become defining moments as a person figures out his place in the world.

That happened to Lightbown in the 1940s when he was 18. He was sent to jail for “being an Indian” after a police officer arrested him, his brother and a friend for picking cherries out of a tree at East 14th and Nanaimo.

A judge convicted Lightbown of vagrancy and he served six months in prison. Upon his release, he was given a letter authored by the solicitor-general of Canada.

“He wrote that it was the greatest miscarriage of justice that had come to his attention,” said Lightbown from a chair in his living room. “I didn’t know anything about the law, except that I know we didn’t do anything wrong. Even if we were stealing cherries, I don’t know how that’s a crime.”

It was an incident, or defining moment, that propelled Lightbown’s life-long pursuit of justice for Aboriginal peoples. The Kootenai First Nation member wanted to know more about his history, his people and what colonialism did to this country.

He became a self-described freedom fighter and went on to co-found the United Native Nations Society (originally called the B.C. Association of Non Status Indians) and Vancouver Native Housing Society.

News junkies may remember Lightbown as a friend to the late William Jones Ignace (also known as Wolverine) and a spokesperson for the Ts’peten Defence Committee during the Gustafsen Lake standoff in 1995 with the RCMP.

Over the decades, he has been a member of various organizations and boards committed to improving the lives of Aboriginal peoples. They include the Aboriginal Healing Foundation and Aboriginal Life in Vancouver Enhancement Society.

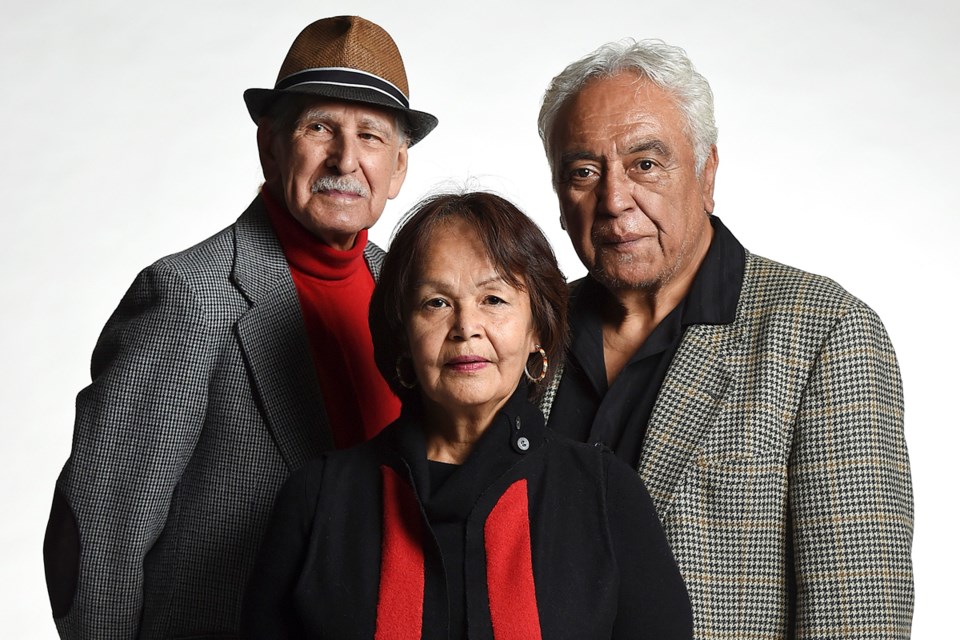

His story brings a unique perspective to what it means to be an Aboriginal person in 2016. So do the stories of elders Lillian Howard, 65, and Joe Fossella, 68, who shared how events in their lives set them on a course to help themselves and others around them.

All three have heard, read, seen or experienced how Vancouver has slowly transformed from a city that excluded Aboriginal peoples to one that wants to include them.

They know the City of Vancouver now has a manager of Aboriginal relations. They know the Vancouver Police Department has 24 Aboriginal police officers and two Aboriginal community safety officers.

They know local First Nations plan to develop land in the city with the goal of improving their members’ lives. They know more indigenous students are graduating from high school. And they know Jody Wilson-Raybould and Melanie Mark made bold statements in getting elected to the highest political arenas in the land.

But what do these moves mean for the average Aboriginal person living in Vancouver in 2016? Is life better? Is it worse? Is it the same as it’s always been?

The questions get back to the Courier’s reason for launching this six-part series in September, which was to look at the transformation of Vancouver through an Aboriginal lens.

The elders don’t have all the answers but recognize their histories provide context to what life was like before, what it is like now and what it could be as Vancouver closes in on 2017.

Struggle and progress

For Lightbown, whose 70-plus years in Vancouver make him an expert on the plight of Aboriginal peoples in the city, his assessment of the decades is that life has improved for many in the indigenous community.

“Life is better for Aboriginal people,” he said. “And the reason it’s better is because of the long struggle that went on with our people and governments.”

That struggle, as Lightbown sees it, is rooted in the oppressive laws of government that set up reserves, seized land, forbade Aboriginal ceremony, excluded indigenous people from voting and rounded up children and took them to residential schools.

It has only been through successful court battles, he said, that progress has been made on these fronts. It has not, he added, been simply a sudden act of goodwill from lawmakers that led to some relief in Aboriginal communities.

“The government and entities are scared stiff that we’re going to use their own laws against them,” he said. “That’s the reason they’re starting to cooperate with us. For years and years, they didn’t recognize us as people. We are the original people from this land and we deserve the recognition and respect that goes with that.”

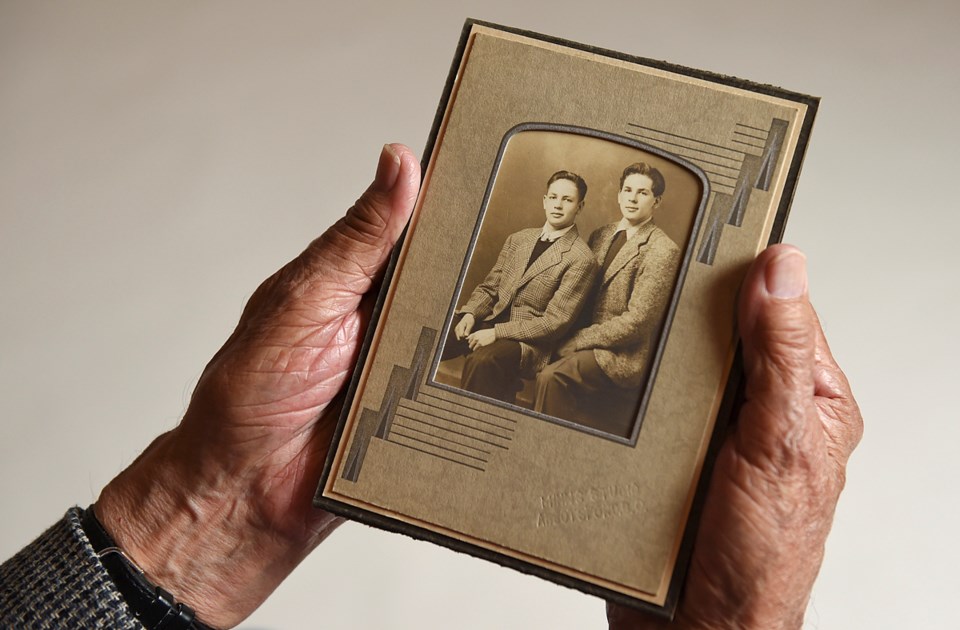

Lightbown’s family roots are in the Kootenays. He was born in Golden and left Revelstoke when he was 15. He rode his bike from Revelstoke to Vancouver, a journey that took him several days, although he doesn’t remember how many.

He moved in with his sister, enrolled at Britannia high school and landed a job on the docks. Over his lifetime, he would have a variety of jobs, including shipyard worker, fisherman, house painter, car salesman, a logger and a cook. He also ran a sawmill with partners in Langley.

As the family history goes, he lost all but a grandmother and uncle to the smallpox epidemic in 1862; the only reason his two relatives survived is because they were in residential schools in Cranbrook and Calgary.

Lightbown never went to residential school and, unlike many Aboriginal people from his generation, has led a life without the challenges of chronic poverty or social ills brought on by historical trauma.

His parents had a lot to do with that, with his mother defying a Catholic priest’s repeated attempts to get Lightbown and his five siblings into residential school; two of his brothers became bomber pilots during the Second World War and a sister worked for Boeing on Sea Island.

His father worked as a signal maintainer for the Canadian Pacific Railway and was considered a community leader. He organized to buy coal for people struggling to stay alive during the Depression, he built a skating rink and was the caller for the local square dance.

“When I came here [to Vancouver] at 15, I had been living in white communities for some time and was disassociated with the Indian side of the family,” Lightbown said. “We kind of worked our way into the white community and accepted things the way they were. That changed after I got arrested.”

In Vancouver, he faced racism at school and on the streets. He had to learn to defend himself with his mouth and his fists. That fighting spirit is still very much alive today.

On the morning of the Courier’s visit, Lightbown had read an article in the morning newspaper about the Supreme Court of Canada’s landmark decision in 2014 to grant title to more than 1,700 kilometres of land to the Tsilhqot’in First Nation.

The story had to do with the Tsilhqot’in filing a claim in B.C. Supreme Court to “private land” on the same territory the band claimed in their historic Supreme Court of Canada victory.

Lightbown had underlined “private land” in red pen.

“That’s bullshit because the reality is, they own the land,” he said. “It’s as if we’re still interlopers and not really sovereign people.”

Lightbown set the clipping on a stack of other news stories piled on his coffee table. Each article has fired him up in some way that he’s put them aside with plans to write letters to the editor about his concerns.

“I just can’t help myself because that’s the way I am,” he said. “There’s enough [clippings] here to keep me busy for three years.”

Lightbown spent a portion of the interview praising the work of firebrand former lawyer Bruce Clark, who was a central figure in the Gustafsen Lake standoff in 1995. The standoff began when about 20 First Nations people occupied a piece of ranch land near 100 Mile House that they said was sacred and part of a larger tract of unceded territory.

In response, the RCMP brought in hundreds of officers, helicopters and armoured personnel carriers and fired thousands of rounds of ammunition. No one died in the standoff.

Lightbown said Clark’s work in the 1970s related to the long-running Ontario land claims case known as Bear Island, where legal arguments made back then were at the root of arguments made in the Tsilhqot’in ruling, was groundbreaking.

“Boy oh boy, if there was one person who deserves that recognition in Canada for advancing rightful ownership of Aboriginal title, it’s Bruce Clark,” he said. “The Tsilhquot’in decision isn’t an accident. It took a lot of work by Bruce Clark and a lot of people to get to that decision. People who came over here and stole the land were pretty damn smart, but what they did was illegal and it still illegal.”

To remind him of the work that needs to be done to help his community in 2016 and into the future, Lightbown frequently hops a bus to the Downtown Eastside.

“I see our people and I see the conditions they’re surviving in,” he said of disproportionate number of Aboriginal people who are homeless, addicted and suffering from mental health issues. “It’s really ugly looking stuff, and it really hurts me. But I have never given up on the people.”

‘A life-long process’

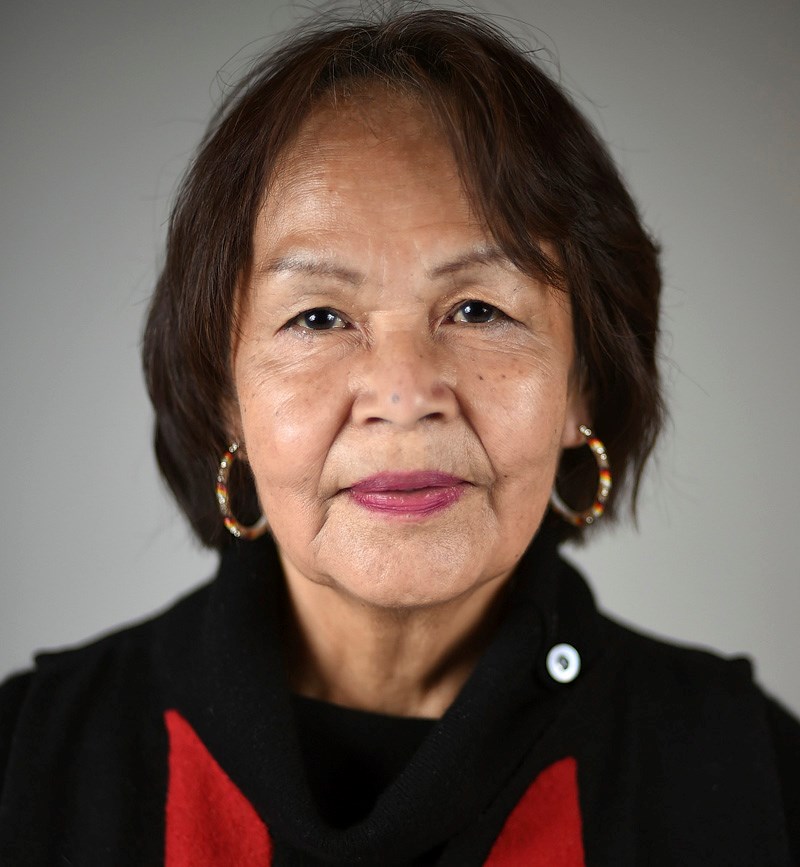

Lillian Howard has been trying to write her life story but is having trouble with some parts of it.

The abuse, the rapes, the domestic violence.

Those parts.

Only recently has she been able to talk about being a victim. Counselling, therapy and treatment have helped. So did opening up in a cultural sensitivity training session that she and other Aboriginal people led for Vancouver police officers.

But the hurt is still there.

“It just takes work every day, every day it takes work,” she said from a rooftop patio of the Downtown Eastside apartment building in which she lives. “It’s a life-long process. I told myself I really don’t want to be a bitter old woman. I want to be able to have my children and grandchildren remember me as a loving, kind mother and grandmother.”

Howard is a survivor of the Christie residential school on Meares Island near Tofino, where she was sexually abused while attending Grades 1 and 2. (A Catholic brother was eventually charged.)

When she turned 12, one of her dad’s cousins was beaten to death by her spouse. Howard and her mother witnessed the aftermath. Howard promised herself then that she would not let that happen to her. But later in life, she too became a victim of domestic violence.

“I was in shock, and it happened again a few weeks later,” she said of the abuse in her marriage, noting she eventually separated from her husband.

Life today in Vancouver, she said, is better for her, and much better than it was when she arrived in the city in the 1970s. She attributes much of that turnaround to her commitment to improve her life, go to university and get involved in community.

Her conclusion about her life, though, is tempered by the reality outside her apartment, where many indigenous people continue to struggle with homelessness, addiction and hopelessness.

She believes government has to do more and has lined up behind the political parties that have shown and signaled that reconciling with Aboriginal peoples is a priority.

Her interest in making change through politics is not new. At 17, she volunteered in Port Alberni to campaign for Pierre Elliott Trudeau.

More recently, Howard supported the campaign of Trudeau’s son, Justin, who has promised as prime minster to a renewed “nation to nation” relationship with indigenous people.

Locally, Howard is a volunteer with Vision Vancouver, a party she praised for its commitment to better relations with Aboriginal peoples and create policy that recognizes the importance of building more housing and protecting the environment.

“Before Vision, the Aboriginal community leaders were knocking at municipal doors for years, looking for support and there was just really no interest,” she said.

Howard knows Mayor Gregor Robertson personally and has been called upon to participate in city-led ceremonies, including accepting a proclamation in council chambers in June for Aboriginal Day.

“I’ve lived in Vancouver since 1976 and I’ve never really felt part of the community until I started doing volunteer work with Vision Vancouver in their first election [in 2008],” she said.

The connections she’s made in the community have opened doors for Howard, who is the co-chairperson of the city’s four-year-old Urban Aboriginal Peoples advisory committee, which carries a lot of weight in influencing city council’s decisions related to indigenous people.

Her resume includes work as executive director of the Aboriginal Policing Centre on Fraser Street, as an Aboriginal support worker in Vancouver schools and staff member at the WISH drop-in centre for women. She has also been a volunteer at the Aboriginal Front Door Society in the Downtown Eastside. Earlier this year, she began a job at B.C. Women’s Hospital and Health Centre, where she works out of the indigenous women’s health program as a support worker for patients and families.

When she moved to Vancouver in the 1970s, she said, racism was rampant. She got followed by staff in stores, received “looks of disdain” and experienced a general unease about her surroundings.

“We weren’t welcome in our own homelands,” she said. “It’s like we were scum of the earth.”

She made friends with some members of the Jewish community and learned that not all non-native people were unfriendly to indigenous people. Her Jewish friends, she noted, faced similar racism. They taught her to be assertive, to stand tall, to not walk in shame.

Howard got a job working for the Union of B.C. Indian Chiefs that involved her traveling around the province to identify issues of concern in Aboriginal communities. She worked there for eight years before enrolling at the University of B.C., where she completed four years of political science and Canadian history. She later got her master’s in environmental education and communication at Royal Roads University.

The interest in the topics are at the root of the work and activism that Howard has taken on in her life. In the early 1980s, she and a group of Aboriginal women occupied the downtown Indian Affairs office for 28 days to protest inadequate housing, poor living conditions and poverty in B.C. More recently, in 2011, she went on a 31-day hunger strike in support of Attawapiskat Chief Theresa Spence’s hunger strike in Ottawa, whose protest was aimed at getting a meeting with then-prime minister Stephen Harper.

Howard believes she gets her fighting spirit from her mother, who was active in their community of Friendly Cove in Nootka Sound, and her father, who was a member of the village council. From an early age, she remembers being defiant. At 11 years old, in the days leading up to her confirmation ceremony, she protested her mother’s wish to have her wear a white dress. She wanted to wear a dress with a rose pattern. In the end, she got her way.

“I remember my grandfather telling my mother you have to let this [child] go, not to shut her down,” said Howard, who is a member of the Mowachaht/Muchalaht First Nation and is of Nuuchah-nulth, Kwakwaka’wakw and Tlingit ancestry. Howard was co-chairperson of her tribal council from 1993 to 1998.

As she considered a question about what reconciliation means to her, Howard told a story about a program that she helped operate with William Wasden Jr. out of community centres in 2014 that involved participants making traditional button blankets and learning indigenous songs.

She coordinated the blanket making and recalls how two of the male participants, who didn’t particularly like each other from the start, formed a strong bond by the end of the sessions. One was white, the other Aboriginal.

“Eventually, they began working on a blanket together and got to know each other and are good friends now,” she said. “That was reconciliation in action.”

She stressed the importance of indigenous culture in playing a part in reconciliation, both for Aboriginal peoples and non-native Canadians.

Many indigenous people in the city and across Metro Vancouver are disconnected from their culture, she said. Connecting them with ceremony, with traditional teachings and community can turn a person “living in fear, isolation and darkness” into one beaming with pride, she added.

Howard’s own healing journey continues, and she’s found participating in an annual canoe event with hundreds of other indigenous people from Alaska to Oregon has helped her get through the dark days.

“It’s really a cultural revival, connecting with water,” she said of the week-long paddling excursion that includes singing and dancing at stops along the route. “It’s really powerful. It’s healing through culture.”

As she looks ahead to 2017 and beyond, Howard said there is a real need to keep fighting for a better Vancouver, a better Canada that includes Aboriginal peoples and celebrates their history. She urged more indigenous people to get involved with the broader community, to stand tall and be proud of who they are and what they can offer in a relationship with non-native groups, diverse communities and political bodies.

“You can make a difference,” she said. “Sometimes, it can take years. But I’m not doing this for me. It’s for my children and for my grandchildren.”

Providing guidance

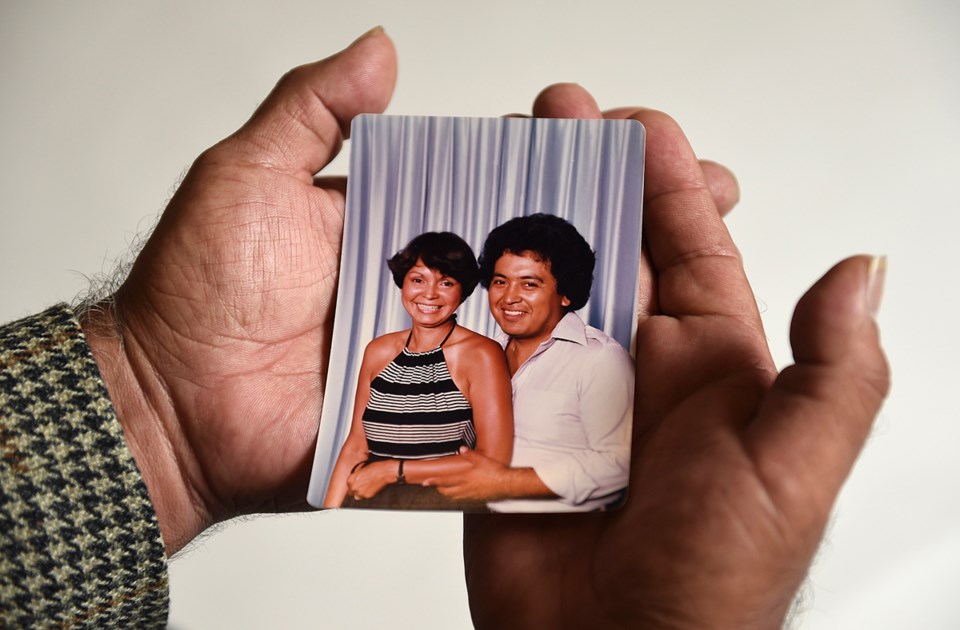

At 68, longtime Vancouver resident Joe Fossella has reached a point in his life where he can proudly take stock of who he is and what’s important to him: He’s been married 49 years, has two sons in their 40s, six grandchildren and two great grandchildren.

He’s happy to talk family as he sits in a downtown coffee shop, noting one of his grandsons is working at McDonald’s, saving for a car and interested in a career as a paramedic.

That’s the present for Fossella.

The past was not so great, not only for him but for his wife, his sons and the people around him. He was the reason for that dark period. It involved booze, drugs and violence.

“I was spiraling out of control real fast,” Fossella, a member of the Sechelt First Nation, said of his life more than two decades ago. “I tried to kill my wife one time. This is like 24 years into our marriage. The behaviour I had was: ‘I’m the king of the castle and you have no right doing anything without asking the king.’ This is what we’ve all learned [as men], pretty much. Yeah, I tried to kill her. I was attempting to probably kill my boys at one time, too. And another time, I went after these three or four guys with my rifle. Fortunately, they were not home that night.”

His wife, Joyce, told him he had to change or she would leave him.

“It wasn’t in anger but she was firm what she was telling me. So I said you find me a doctor that’s going to fix me. And she tried, but it didn’t work.”

What worked was Fossella finding a relationship counselling and anger management program in North Vancouver called Change of Seasons; one of his sons, unbeknownst to him, was already a participant. Fossella completed the program twice. Coordinators were impressed with his turnaround and saw in him a commitment to help others in the same situation. He enrolled at Native Education College and completed a family and community counselling course.

“I took it and here I am.”

Where Fossella is now is 22 years into being that person who provides guidance to men seeking to manage anger and violence and embrace peace, culture and spirituality.

He worked a few years for Change of Seasons before he and the late Daniel Parker founded Warriors Against Violence, a program they launched 19 years ago out of the Kiwassa Neighbourhood House, where an average of 400 clients per year seek help.

Fossella’s wife, Joyce, is the executive director.

“I’m very grateful for her supporting me through my troubled times,” he said of his wife. “I was an alcoholic and tried to blame alcohol and drugs for my problem. But it wasn’t that, it was me. All that bottled-up anger, hurts and pains that I was carrying was starting to bubble out and I became more violent and abusive. And being drunk sometimes intensified that anger.”

That pain relates to being sexually abused by a stranger and having his father beat him and his mother. These are details he shared at his first therapy sessions. Such details are not uncommon in the stories he’s heard from participants in his program.

The goal of the sessions, which are free to participants, is to break the cycle of anger and violence, which Fossella acknowledges is a difficult task considering the generations of learned behaviour.

“My purpose is to help them unlearn those unwanted behaviours and help themselves live a better life, forgive themselves, love themselves and ask for forgiveness from the ones who hurt them and the ones they may have harmed.”

Men from various backgrounds attend the sessions, although participants are predominantly Aboriginal, some of whom with court-imposed conditions related to an assault charge. Wives and girlfriends also attend — some on separate nights from the men — to learn about what’s being taught and the tools needed to manage a spouse’s anger.

Fossella’s passion for the work, though, is somewhat diminished by his concern the program won’t be around much longer, if more funding is not available. He believes too much money is being spent on organizations that are failing Aboriginal peoples in need.

“Other agencies get funding to do what we’re doing, but they don’t know what they’re doing, they can’t handle the people so they send them to us,” he said, noting he and his wife recently trained 13 people in Saskatchewan from various reserves on how to counsel its members.

Warriors Against Violence, which has a staff of seven people, operates on an annual budget of $100,000. Every year, Fossella and his wife have to lobby for funding. He supplements his income by working part-time at transition houses for Aboriginal men. Last year, a GoFundMe campaign was launched but has only raised $1,930.

As governments continue to make commitments to reconcile with Canada’s indigenous people, Fossella believes programs such as his should be properly funded and expanded. After all, he said, teaching a man to manage his anger and keep him out of jail saves taxpayers a ton of money normally spent on policing, health care and the courts.

“You can imagine the amount of dollars we can save someone who might go to a psychiatrist or psychologist,” he said, recognizing that many residential school survivors received financial compensation tied to the truth and reconciliation hearings. “That benefited some peoples’ pockets. But I didn’t really see enough people out there trying to help pull all that garbage out of a person, so they could safely love themselves, and go from there to help out their grandchildren and great grandchildren.”

Anger and violence, he said, is at the root of many tragic circumstances Aboriginal peoples find themselves in — whether it be alcoholism, drug addiction, homelessness or mental health problems. From what he’s seen and experienced himself, victims become perpetrators and the cycle of violence continues.

He is encouraged by the elections of Jody Wilson-Raybould and Melanie Mark and their commitments to be voices in government for Aboriginal peoples.

“It’s quite remarkable for our peoples. It’s been a short while since they were elected but I hope to see some results coming from their titles. They’re representing a lot of people.”

He is also happy to see that B.C. judge Marion Buller, a member of Saskatchewan’s Mistawasis First Nation, was announced as the chief commissioner of the National Inquiry into Murdered and Missing Indigenous Women and Girls.

He learned of Buller’s appointment when his wife called during his conversation with the Courier. Fossella and his wife are familiar with Buller’s work in founding B.C.’s first First Nations court in New Westminster.

“She’s a real, real advocate for Aboriginal people. I really know she’ll put forward 100 per cent into her work, and I’m really grateful she got the position.”

As Fossella gets closer to his 70th birthday, and reflects on his past and what the future might hold for the Aboriginal community, his thoughts return to the importance of his work.

“You know, there are times when I’m getting tired and I say I’m going to quit and find a sweep-the-floor job somewhere. But then I see one of the participants smiling like crazy and I know he gets it, that he knows what I’m talking about and he feels the weight of the world has been lifted off his shoulders. That’s what gives me the motivation to keep doing what I’m doing.”

‘A long ways from that’

Back at Lightbown’s apartment, the interview has come to a close.

Lightbown knows he’s getting on in age and won’t be around to see what life will be like for Canada’s young Aboriginal peoples as they become adults and raise families.

Yes, he said, progress has been made since his first days in Vancouver. And he believes Trudeau is committed to have the Canadian government improve its relations with indigenous people across the land.

But the old freedom fighter is suspicious.

“And I’ll continue to be suspicious until such time as reconciliation really takes place. We’re a long ways from that.”

In the meantime, he has this wish.

“Regardless of the fact that this is my land, I want this to be a happy community and I want the people who are living here to be happy with each other. There’s no reason why it should be any other way.”

[email protected]

@Howellings