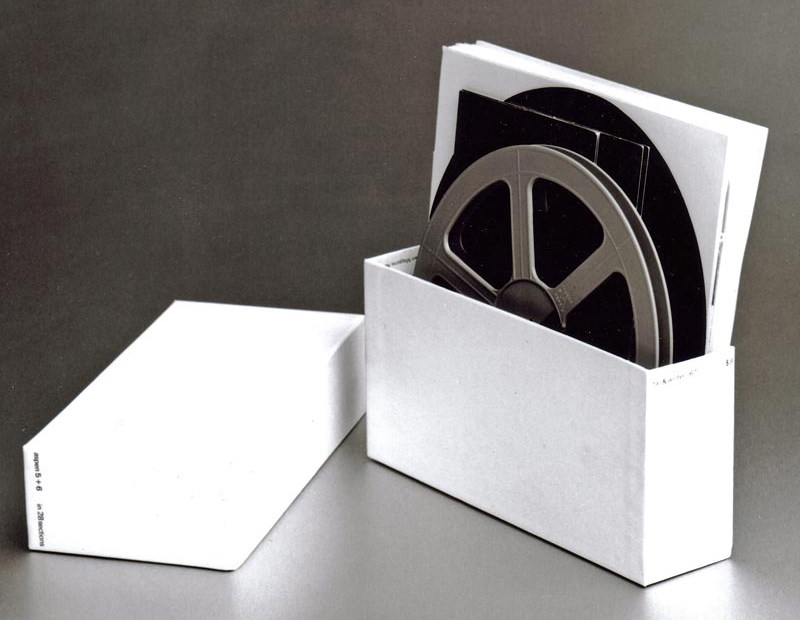

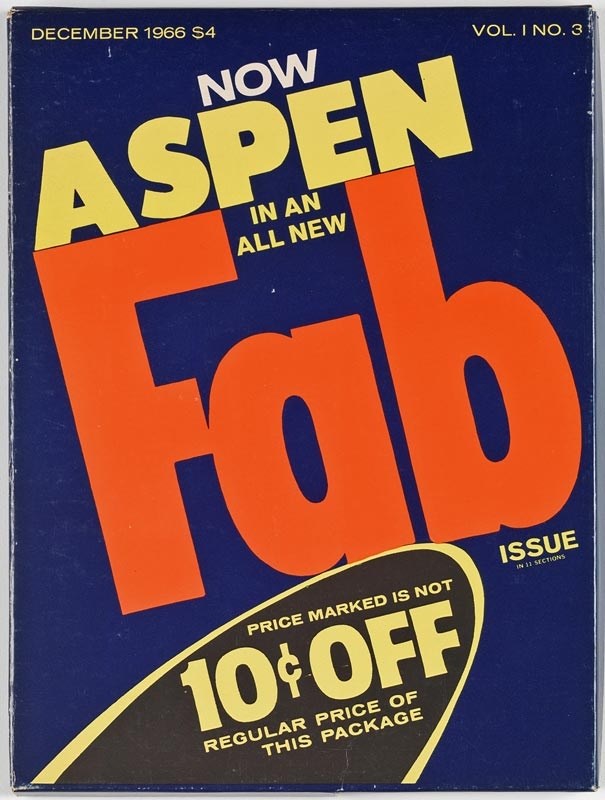

In world where you read most of your favourite magazines in two-sentence summaries in your Facebook feed, it might be hard to picture a magazine that came contained in a cardboard box – filled with tangible unbound contents such as pamphlets, posters, records, reels of film and other objects.

But that’s exactly what Aspen Magazine – which featured contributors such as Andy Warhol, Willem de Kooning, Ian Hamilton Finlay, David Hockney, Jasper Johns, Allan Kaprow, Ed Ruscha, J. G. Ballard, Bill Evans, Philip Glass, the Velvet Underground and Yoko Ono – was, and what the visiting exhibition Aspen Magazine: 1965-1971 at the Charles H. Scott Gallery at Emily Carr has been highlighting since November.

As part of the exhibition, the gallery now welcomes Gwen Allen, author of Artists’ Magazines: An Alternative Space for Art (MIT, 2011) for a talk on the subject.

On Jan. 22, 6pm at the Emily Carr Lecture Theatre, Allen will discuss Aspen, exploring its function and importance as an alternative exhibition space in the 1960s and ‘70s. She will also explore the history of artists’ magazines, designed by and for artists, and distributed “not according to the motives of profit, but according to the artistic, social, and political ideals they sought to convey.”

We caught up with Allen for a preview of the talk:

What was Aspen?

Aspen was a groundbreaking multimedia artists’ magazine that functioned as a miniature traveling exhibition space.

Why was it groundbreaking?

Aspen was significant because it functioned as a nexus for the 1960s avant-garde. However it also brought together different generations of artists (featuring, for example, Hans Richter and Marcel Duchamp alongside John Cage and Sol LeWitt). Futhermore it was a site of transatlantic dialogue, featuring artists and writers from Europe and the United States side by side. Finally, it was significant in its intermedia nature – it brought together visual artists alongside writers, dancers, composers, filmmakers, and musicians, mirroring the expanded field of art itself in this time period.

Can you place Aspen in context alongside other pivotal artist magazines in history?

It was one of many fascinating and innovative artists’ magazines published in the postwar period. Other boxed and multimedia publications include SMS, Fluxus, and Decollage. These publications were artistically significant in that they reflect the changes in art during this time period – i.e. the trend for artists to work in new and different media. However they also reflect the ideological and political aspirations of these artists to make their work accessible and reach wider audiences.

Is there a contemporary example of something similar?

Today so many online publications, even mainstream ones such as the New York Times are multimedia, including videos, audio, etc. – in some ways these inherit the notion of a multimedia multimedia platform that Aspen tried to embody. There are also a handful of limited edition artists’ periodicals that utilize a boxed or multimedia format. Something like Visionnaire, while different than Aspen in its luxury format, is one example. There are also online publications, such as Triple Canopy that are thinking about the relationship between traditional print and online multimedia publications in self-reflexive ways.

Describe the history of artist magazines – why are they important?

Artists’ magazines have been essential for avant-garde movements going back to the early 20th century.They were important vehicles for defining artistic agendas and circulating ideas and manifestos. In the postwar period they became especially important within the context of conceptual art, which so often depended on textual and/or photographic documentation. They have also been extremely important to various kinds of alternative artistic practices and communities – from the feminist art movement, to performance art, Earth art and video – offering an alterative to mainstream media coverage.

What is the state of the genre?

Today, a moment of unquestionable crisis and transition for print media – artists are both revisiting and expanding upon these earlier practices, with a renewed interest in the potential of the magazine, even as they reflect upon its transformation by new digital technologies, online communication, and social media. At the same time, artists are returning to the printed page, as we see in the recent proliferation of artists’ periodicals and zines, as well as conferences, fairs, exhibitions, and academic programs devoted to such publishing activities.

Here is a short excerpt from her book:

Artists’ magazines were produced and distributed not according to the motives of profit but according to the artistic, social, and political ideals they sought to convey. Edited and designed in loft spaces and distributed at independent and artist-run bookstores such as Printed Matter in New York and Art Metropole in Toronto— or sometimes given away for free— these publications were influential well beyond their limited circulations and brief life spans.

Against the slickness of mainstream art magazines with their glossy finish and high-quality color reproductions, artists’ magazines expressed anticommercial, egalitarian sentiments through their unpretentious, do-it-yourself formats, such as mimeograph and newsprint. Often penniless, they relied on grants, meager advertising, and subscription revenue and the (usually uncompensated) intellectual labor of their editors and contributors. Their advertising sections were more likely to broadcast political statements or promote nonprofit spaces than to sponsor commercial galleries.

Criticism and exhibition reviews were replaced by artists’ projects, writings, and interviews, through which artists “talked back” to critics and took charge of the public discourse around their work. Letters to the editor became sites of protest, expressions of solidarity, and occasions for inside jokes. Mastheads reveal how the divisions of labor between editors, critics, designers, and writers blurred and overlapped, giving way to new kinds of collaboration rooted in intellectual exchange and camaraderie.

Magazines track the formation of such relationships, and record conflicts and differences of opinion—disagreements over which editors resigned, friendships dissolved, and sometimes publications themselves even came to an end. —(Gwen Allen, Artists’ Magazines: An Alternative Space for Art. MIT Press, 2011, p. 8)

You can hear more from Gwen Allen Jan. 22 at 6pm in the Emily Carr University Theatre (Room SB301). The lecture is in conjunction with the ongoing exhibition Aspen Magazine: 1965–1971 at Emily Carr and is free to attend.