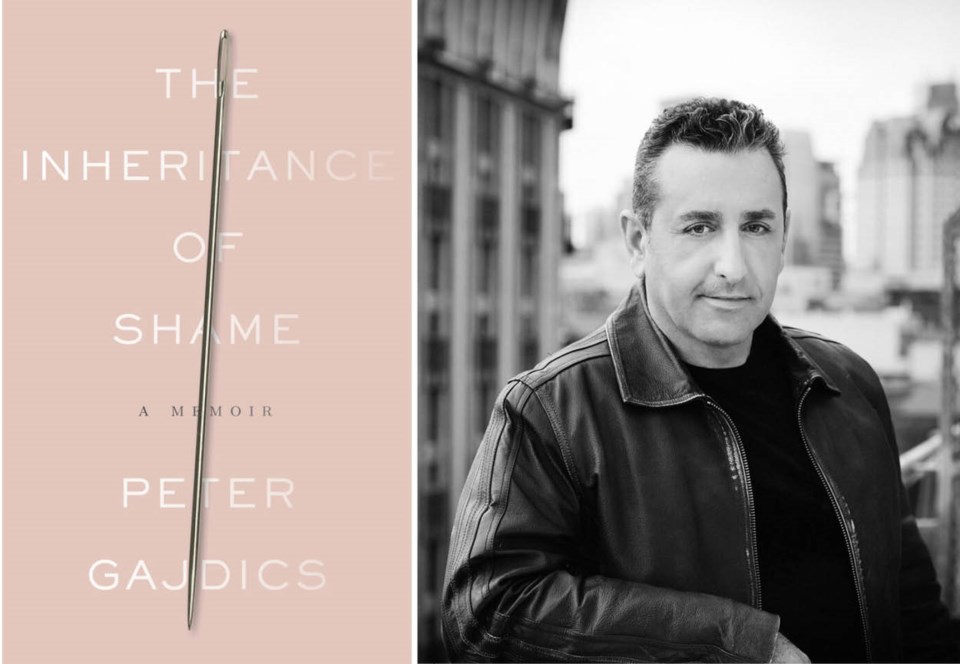

Vancouver-based author Peter Gajdics recounts memories surrounding universal themes of childhood trauma, oppression and intergenerational pain in his debut memoir The Inheritance of Shame. The memoir revolves around the six years the Canadian-Hungarian writer spent in a strange form of conversion therapy in British Columbia in an effort to “cure” his homosexuality. Gajdics details his interactions in the cult-like home where patients were controlled by a dominating, rogue psychiatrist who created an exploitative sense of family. Told over the span of a decade, the memoir aims to remind readers of the importance of resilience, compassion and the courage to speak the truth.

My decision to leave Vancouver, to remove myself physically from my immediate environment as soon as possible, appeared inside of me with panicked urgency the morning after the night with the man who paid me money for sex for the first time.

I called the University of Victoria on Vancouver Island, a two-hour ferry from my hometown of Vancouver, and asked for all the paperwork for undergraduate studies.

I told my parents I was moving to Victoria to start my bachelor’s degree in creative writing; then, to assuage their visible concern, added, “maybe journalism.”

Before my first day of classes, I made an appointment to see a new near-retired general practitioner, referred by my general practitioner back home. When I saw him the next week, I told him that I needed to see a psychiatrist.

“Can you please itemize for me what you’re looking for?” he asked.

“Some sort of therapy where I can do more than talk, although . . . I guess I also need to talk. I need . . .” I pushed my fist into the pit of my stomach, near my belly button, like I was trying to reach my own umbilical cord. “Something . . . deeper. I know I need to cry.

But I don’t want to take medication.”

“There is one doctor, a Spanish man, who’s just moved to the city from back east. Quebec, I think. He’s also the only psychiatrist practicing psychotherapy that’s accepting new patients. I’ll see what I can do . . .”

• • •

I was sitting on the only metal chair in a yet-to-be finished waiting room when I smelled his pungent cologne, like the scent of an animal that had laid claim to its territory. Moments later, his office door swung open with a gust of wind.

“Are you Peter?” he said in a pronounced Spanish accent. “I’m Dr. Alfonzo.”

The smell was his.

I stood up and smiled, shook his hand, and followed him back through two adjoining doors that opened up inside a large, empty room, a windowless chamber, still being constructed.

“My furniture’s being delivered next week. Until then, we can sit here,” he said, pointing to two rickety stools.

We sat, and he started writing notes before I’d said a word. Olive skinned and around 50 years old, he was dressed in black, head to toe, with short, graying hair, wild, bushy eyebrows that hung over his long, dark lashes and a closely cropped goatee. No doubt he’d once been handsome. Now he looked more menacing and slightly disheveled.

“How do you pronounce your last name?” he asked.

“Guy-ditch,” I said. “As in a ‘guy-in-a-ditch.’” I cracked a smile.

He was not amused. “When I was a kid we actually pronounced it ‘Gay-dicks.’”

He looked up from his yellow, legal-sized notepad. “Why would you do that?”

“My father Anglicized his name after the war. I guess he wanted to make it easier on North Americans.”

“Which war?”

“World War II. He didn’t really know what he was doing, changing the pronunciation to ‘gay.’ He’s Hungarian; he couldn’t speak English. Growing up was a cruel joke.”

“Why?”

He waited for me to explain what I thought had been obvious. “Well, growing up with the name ‘Gay-dicks,’ and turning out gay.”

“You’re gay?” He raised an eyebrow, scanned me up and down.

“Yes . . .”

“You told your parents?”

“Last year.”

“What did they say?”

“That they’d never accept it, that it was immoral and I should never talk about it again.”

He looked back to his notes and scribbled away. “So. . . why do you want to see a psychiatrist?”

“Why? I guess . . . I want to feel more control in my life.”

“You feel out of control?”

“I feel like I’ve lost everything that matters to me: my parents, their love. I was trying to be honest, telling who I am. And now . . .”

“Yes?”

“How do I come to terms with who I am when who I am causes so much pain and suffering to everyone I love?” I started crying.

“We won’t have any of that.” He motioned with a flick of his pen for me to cease all tears and to get on track. “No crying. Not now. Not yet.” His thick accent shook me from my pain. He looked back to his notes as I closed the door to my tears, something I’d become an expert at since childhood.

“Are you depressed?”

I blushed. The truth was I had lived in the country of depression for so long it felt like my home. “I suppose.”

“Do you have a boyfriend?”

“No.”

“Do you want one?”

“I don’t trust men.”

He glanced up again, but this time his eyes seemed to be photographing my every inch for future recollection: my swarthy complexion, my long black hair tied back in a ponytail, my closely cropped beard and mustache.

“And women?”

“I’ve always had women friends, a girlfriend, even, but . . . sexually, that’s never really worked.”

“You can’t maintain an erection?”

“No. I mean, that’s not it, it’s just . . . I always end up thinking about men when I’m with women. But when I’m with men, I . . .”

“Yes?”

“I feel like a crippled heterosexual.”

The words hung between us like an onerous confession. He turned back to his notepad and scribbled some notes. I tried to fix my eyes on the upside-down writing, but all I could decipher were arrows and tables and what looked like some kind of shorthand.

“There was also an incident,” I added, almost as an afterthought. “When I was six.”

“Incident?”

“Sexual abuse.”

“You were abused?” His interest piqued. “Who abused you - a family member?”

“A stranger. During a church bazaar in my elementary-school bathroom.”

“Where were your parents?”

“Somewhere in the crowd, I don’t know.”

“How did it end?”

“I don’t remember it ending.”

“Did you tell anyone?”

“No.”

“You never discussed it with anyone?”

“Not really.”

“What do you mean, ‘not really?’”

“When I was 13, my mother sat me down in the kitchen after school one day and she told me that there were dirty old men who kidnapped little boys and made them do really bad things that turned them into perverts for life. Then she just stared at me.”

“What did she mean by that?”

“I don’t know. I was too afraid to ask. ‘Beware who you’ve become,’ I guess.”

“Meaning?”

“Like I said, I didn’t ask her, and she never explained. I was too scared.”

“I’m thinking of setting up a group solely for gay men,” he said. “I think you’d be a perfect fit. But we need to take care of what’s really bothering you. It would be a mistake to focus on your homosexuality. Your sexuality will take care of itself.”

• • •

Peter Gajdics is a Vancouver-based writer with international by-lines in publications including The Advocate, The Q Review, New York Tyrant, The Gay and Lesbian Review/Worldwide, Gay Times, The Printed Blog and Opium, where he won the 2009 500-word memoir contest. For more on Gajdics and his debut memoir, visit inhertitanceofshame.com.