I make a partial living by trafficking in words. So I’m well aware how often copywriters, publicists, policymakers, politicians, bloggers and trolls weaponize words against the public.

The problem is bigger than the decline of journalism in the digital age. It’s bigger than a dumbed-down Empire that spat forth a former reality TV star as a winning presidential contender. Think of how one simple word, “freedom,” has been used for decades as a semantic bludgeon for imperial goals. Too often, we’re led to mistake rubbery terms for hard-core reality, according to the late American writer Robert Anton Wilson.

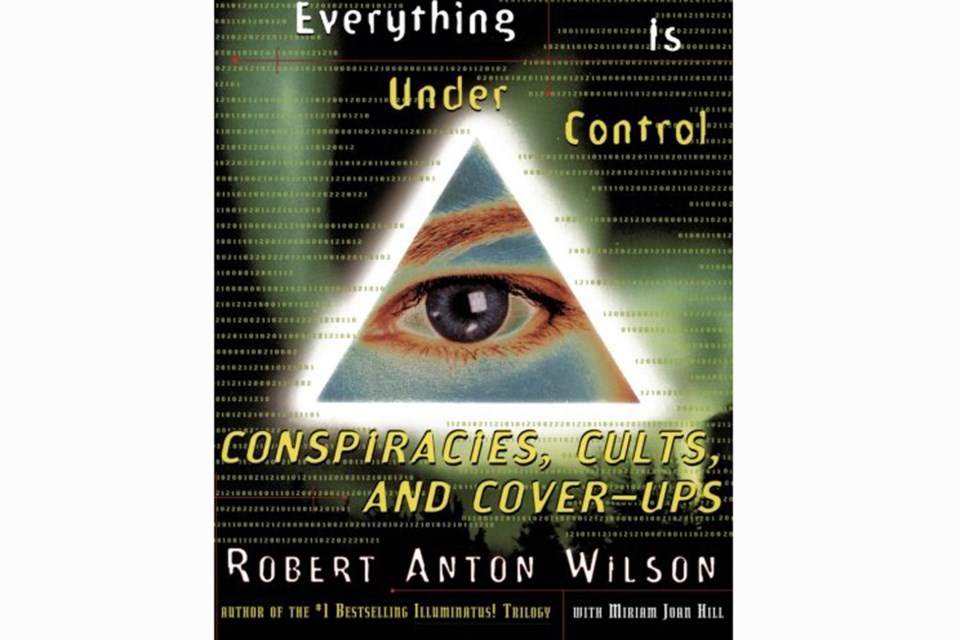

“In other words, because we can say ‘the Jews,’ or ‘the New World Order,’ or ‘the patriarchy,’ we can believe, or almost believe, that these grammatical abstractions have the same kind of reality as basketballs, barking dogs, and baked beans. Individuals, with all their hair and fingernails and ideals and delusions and funky smells, disappear, as it were, and the world becomes haunted by collective nouns,” the author wrote in his 1998 book Everything Is Under Control.

Ah, to be free from the hypnotizing fog of collective nouns. During the last brief sunny stretch, I went for a long hike far from the news — factual, fake and frivolous. Over a ridge top I found a solitary oak standing in an amphitheatre of moss. I sat under the oak and looked out across the strait.

Hearing a sound in the distance, I caught sight of a small deer looking out from the trees. It’s uncommonly rare to see an animal in the wild without it sensing you first, but this fawn loped uphill in my direction, oblivious to my presence. Closer and closer it came. It veered off only a few yards away from me, with a bouncy gait that seemed a bit... much.

Up close, I could sense this young creature’s joy at being alive. Perhaps I’m anthropomorphizing here, but it felt as real as the tree trunk against my back. I felt grateful to witness this wordless moment of animal grace.

“A name is a prison, but God is free,” wrote the Greek poet Nikos Kazantzakis. When we’re very young, we lack names for the wondrous things around us. But as we age, we begin to suffer from “hardening of the categories.” Our ideas of right and wrong, real and fake, harden into divisive certainties. It’s an affliction unique to our species.

This is one reason humans love their household pets: for their spontaneous, language-free response to the world.

In Kurt Vonnegut’s 1985 novel Galapagos, a group of holidaying celebrities are shipwrecked after a global economic meltdown. A world epidemic of infertility follows, leaving only the ship survivors untouched. Their descendants devolve over millennia into seal-like creatures, with diminishing intelligence shading into in-the-moment joyfulness.

Thanks to their smaller brains, humanity’s successors are incapable of science, art, industry and war. But they are at last in tune with nature — and happy.

Today’s evolutionary trends are even stranger than Vonnegut’s sci-fi scenario. Our electronic networks appears to be getting smarter even as we become dumber — if not measurably stupider, then at least overly dependent on our gadgets for the simplest of tasks. How will this end? With the planet’s apex predator going from steward of a computer “singularity” to its slave? Or perhaps its pet?

Against all odds, I’m hoping our species will continue to have an edge over our clever creations, and we learn to value perennial wisdom over technical wizardry.

But what will keep us from constantly mistaking the map for the territory, and assuming our collective nouns have a one-to-one correspondence with the external world? Teaching our young deep critical thinking skills would go some way toward enlightenment, I believe.

Almost a century ago, the writer H.G. Wells defined civilization as “a race between education and catastrophe.” The finish line is looming. We need to choose our words carefully.

geoffolson.com