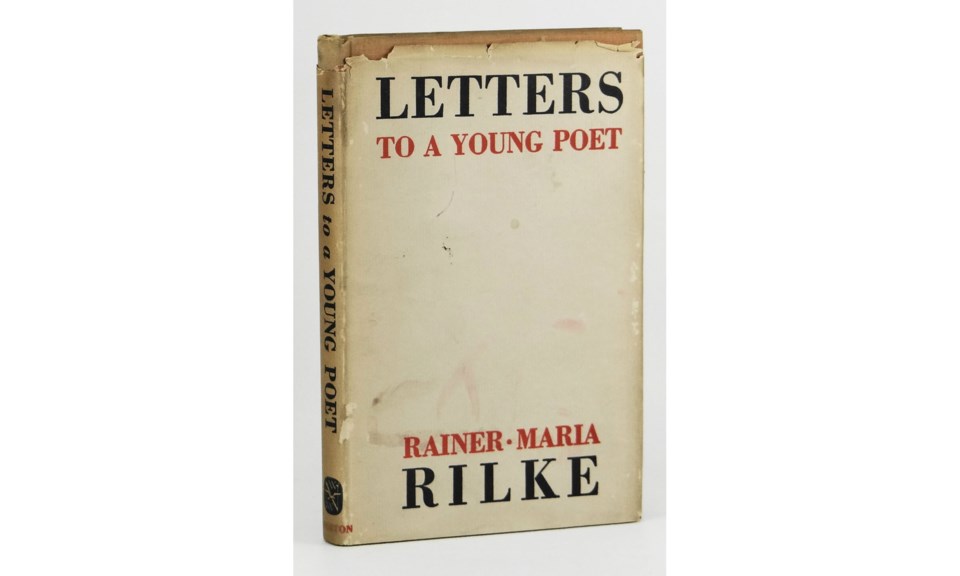

On one of the last hot days in August, I made my way to the beach with a dog-eared paperback translation of Rainer Maria Rilke’s Letters To a Young Poet.

The slim book consists of 10 posted responses from the writer to a 19-year-old military cadet and aspiring poet, Franz Xavier Kappus. The correspondence between Rilke and his young fan lasted from 1902 to 1908.

Like most great literature, it has stood the test of time. Rilke’s advice about navigating the world with integrity and imagination remains as pertinent to today’s “cultural creatives” as it was in Kappas’s time. Other than recommending one other author for his correspondent to read, Rilke cites no experts. He makes no references to abstracts from refereed journals. He appeals to no authority beyond his own humble awareness.

“I beg you, to have patience with everything unresolved in your heart and to try to love the questions themselves as if they were locked rooms or books written in a very foreign language. Don’t search for the answers, which could not be given to you now, because you would not be able to live them. And the point is to live everything. Live the questions now. Perhaps then, someday far in the future, you will gradually, without even noticing it, live your way into the answer,” Rilke writes.

In an era of rampant self-promotion, when we’re expected to “brand” ourselves by curating our social media profiles, such open-ended advice goes well beyond “likes” and emoticons.

“Don’t be confused by surfaces; in the depths everything becomes law. And those who live the mystery falsely and badly (and they are very many) lose it only for themselves and nevertheless pass it on like a sealed letter, without knowing it,” Rilke adds.

These words echo the tempo of a vanished era, when people’s lives were in tune with the rising and setting sun rather than the megahertz cycles of the microchip. Written communications required time to compose and mail, with days to weeks between sending and receipt.

There were no fast responses to knocked-off questions, no instant expertise with cascading comments on Twitter and Facebook. Trolls were limited to children’s fairy tales.

Letters carried a tacit assumption of privacy. So friends, lovers and family members laboured over their missives to reflect their inner lives. Words on paper were an extended form of touch.

I set the book aside on the sand, leaned back and adjusted my hat. The sun’s image fractured into gleaming shards on the waves. I thought back to the words of that stand-up poet, Louis C.K. As a guest on Conan a few years back, he remarked on what smart phones have taken away. “It’s the ability to just sit there like this,” he said while twiddling his thumbs and looked absently around him. “That’s being a person, right?”

It’s those solitary moments, when there’s not a heck of a lot is going on, that constitute the seedbed of the soul. That’s “being a person,” without ersatz connection to dozens of “friends” you’ve never so much as shared a meal with.

There’s plenty of great things about the digital age; no need to number them here. But all things have a dual nature, and that obviously extends to consumer technology. The options for aimless distraction were few in Rilke’s time, which may have meant more boredom but also more free time to think and feel. The telegraph was relatively new, radio was still in the future and television was even further on the horizon. Back in the analogue age, the greatest bandwidth and fastest interactivity wasn’t found in gadgets, but in the human beings next to you.

I gathered up the book and the rest of my stuff, but my phone was nowhere to be found. Annoyed, I returned to the car expecting to find it in the hatchback. Not there. I checked the roadside by the driver door, cursing. The feeling of mounting panic vapourized when I saw the

Blackberry’s red light blinking between the front seats.

In my agitation I had a mini-cardiac routine without any exercise. I was reminded again how reliant I am on my digital pacifier, and realized how much I enjoyed being without it when I had only sun, surf and a dead bohemian poet for company.