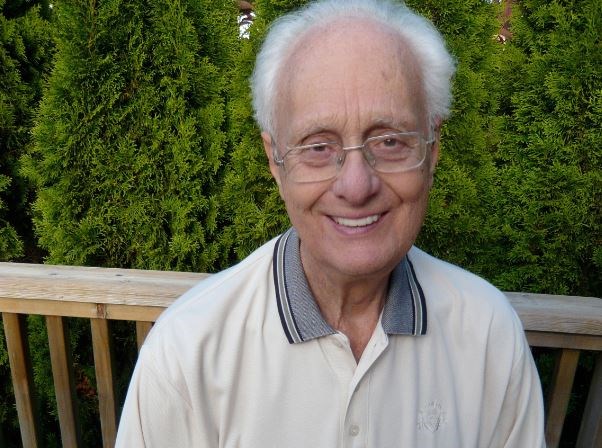

Most of them were expecting yet dreading the news but it wasn’t until he recently made it official this past summer that the outpouring of emotion really took hold. They were his patients, the news was his retirement, and he was the family doctor they adored — in some cases for more than half a century.

One of them — a former trucker, a patient of 51 years — who spent the past 35 travelling from Coquitlam to Vancouver for his appointments, came in the day Dr. Lyall Levy hung up his white coat for the last time at the Marpole Medical Clinic. In the preceding weeks, the doctor had exchanged many tears, memories and hugs with patients, but he didn’t expect more than a polite thank you and a firm handshake from this one. When the patient broke down, the doctor did, too. And then the patient’s wife followed suit. Dr. Levy says he will remember it as among the most moving moments of his professional life.

He also says that he wishes that all the new medical school graduates could have been at his office to see these interactions, to witness the culmination of a career in traditional family practice and the connections that are made with patients — ones, he insists, that can’t ever be duplicated in the now ubiquitous walk-in clinics.

Human medicine

His passion for helping people is something that I have been privileged to be privy to my entire life. And while I could devote well more than an article to Dr. Levy the Dad, this one is about Dr. Levy the Doctor. On that note, I can tell you that it is entirely humbling to think that he has devoted more years than I’ve lived, to serving his profession, his community and his patients — some of whom are third and fourth generation family members. What I can’t tell you though is how often, upon learning that I was Dr. Levy’s daughter, I listened to patients sing my dad’s praises — the common thread being not only the extraordinary medical care but the humanity he showed, when they, or their parent or child, needed it most.

Yet my dad, modest to a serious fault, never sought accolades. That said, he was deeply honoured when he received the Award of Excellence in Medical Practice (2011) from the College of Physicians and Surgeons of B.C. And until he reads this, he probably won’t know that he is among a small group of physicians in the province who have served more than 50 years.

What most of his patients don’t know is that Lyall Levy was an accomplished athlete in his youth and that his path to becoming a doctor could have been sidelined if it wasn’t for my late grandfather’s surreptitious meddling. He asked the then-scout for the New York Rangers, Scotty Milne, not to recruit my father, whom he was eyeing as a potential for the farm team, because my working-class grandparents dreamed of their only child becoming a doctor. If not for this, my dad may well have become a professional jock, not a doc. (He still did get to play basketball for UBC so all was not entirely lost.)

Decades of change

What has transpired during his tenure in medicine is remarkable.

Dr. Levy began practising full-time in 1963 — three years after the birth control pill became available in Canada, on the heels of the release of the oral vaccine for polio, and decades before MRIs became part of the medical vernacular.

Despite being the ‘60s, he had to convince the chief of obstetrics at Vancouver General Hospital that one of his patients was not a subversive but a soon-to-be-father who simply wanted permission to attend his child’s birth.

But for all the progress in medicine, there were personal setbacks as well. My dad was devastated when he and the emergency room physicians were unable to revive one of his dear friends when he suffered a massive heart attack at age 35.

And on Mother’s Day in 1989, a multiple-alarm fire ignited in his Marpole office — the result of an addict’s freebasing gone wrong. It took a year to reconstruct the building but much longer to replace the vital medical information on the charred patient charts.

More recently, he faced prostate cancer, during which the only change he made to his work schedule was to book off early to get to the B.C. Cancer Agency for daily radiation treatments.

Most of his patients were unaware of his health challenges because my dad remained focused on helping them with theirs.

And when, in the wake of his treatment, he landed up in VGH emergency with a serious complication, he sat patiently in the overcrowded waiting room, never considering “pulling rank” to fast track his way through.

Curiously, having Dr. Levy in the house didn’t mean having a top doc on hand (or easy access to any drugs but expired ibuprofen). He seemed to be the textbook case for why physicians shouldn’t treat their own families, and absolutely not themselves.

The loss of objectivity is well-documented and, in our family’s case, translated into none of us supposedly ever needing acute medical care. Just ask my mom about her one-and-only rollerblading attempt-turned-accident. At one with the pavement and unable to move, my dad kept insisting she should just get up.

My sister and I overruled the good doctor, called an ambulance, and the upshot of that broken shoulder was three surgeries over the next two years.

His self-diagnosis attempts were even more offside, perhaps best illustrated by the morning he declared he was “feeling pretty good” when his blood work results came back an hour later indicating he was in kidney failure. (Yes, that’s when he ended up in emergency.)

5 a.m. starts

But back at the office, he was the esteemed physician, the one who arrived early but had already been up for hours. He “worked” his first shift at Bean Brothers in Kerrisdale, where the baristas opened at 5 a.m. for him and he helped them set up the outside chairs.

On the day of his retirement, one of Dr. Levy’s patients surprised him by organizing the staff and early morning regulars to hold a little celebration, including a “Happy Retirement” banner and free coffee.

He’s been sitting in the same seat by the front window, usually six days a week, since it opened 21 years ago, and he still goes there despite him and my mother having moved downtown five years ago from Dunbar-Southlands.

So my daughterly bias aside, it’s fair to say that Dr. Levy is a rare vintage, the kind of doctor who still happily made house calls, who wrote his medical-legal reports in longhand for more than five decades, and who undoubtedly will be warmly greeted by generations of families when they have the pleasure of running into him in Vancouver, as he transitions into retirement, somewhat reluctantly, after 51 rewarding years.

Some may wonder what will happen to all of Dr. Levy’s patients. My dad, determined to ensure that they were not orphaned, lined up an experienced, capable physician to fill his size 11 shoes.

I think they’ll like my husband, even if they struggle to pronounce his rather cumbersome last name.