A report going before city council next week shows a trajectory that city staff say is contributing to homelessness, with the number of rooms available at the shelter rate of $375 per month plummeting from 1,700 in 2003 to 77 last year.

The 16 per cent rent hike in the private hotels, which are located primarily in the Downtown Eastside, equates to a $483 per month cost increasing to $561. The number of rooms renting at twice the shelter rate — $700-plus — has doubled from 363 to 769 rooms.

A separate report conducted by the Carnegie Community Action Project in 2018 found average rents in privately owned hotels to be even higher than those reported in the city report — $663 per month.

“Rents are increasing faster in private buildings that change owners,” said the report, noting the average yearly rent increase among buildings sold was 10 per cent compared to four per cent in those kept off the market.

Between 2015 and 2019, 24 private single-room-occupancy buildings change hands, with prices ranging from $64,000 to $310,000 per room, for an average of $108,000 a room. New owners have primarily been investors, the report said.

Such increases in rents have forced tenants to find other accommodation, check in to a shelter or end up on the street, with the dual public health emergencies of the pandemic and opioid crisis exacerbating the struggle for people on low incomes.

Approximately 60 per cent, or 1,900 of the residents living in privately owned hotels rely on income assistance. Almost half of those residents pay more than 50 per cent of their income on rent.

The report showed there were 6,680 open hotel rooms in the downtown core last year. A total of 55 per cent were privately owned and the remaining 45 per cent owned by government, or a non-profit agency.

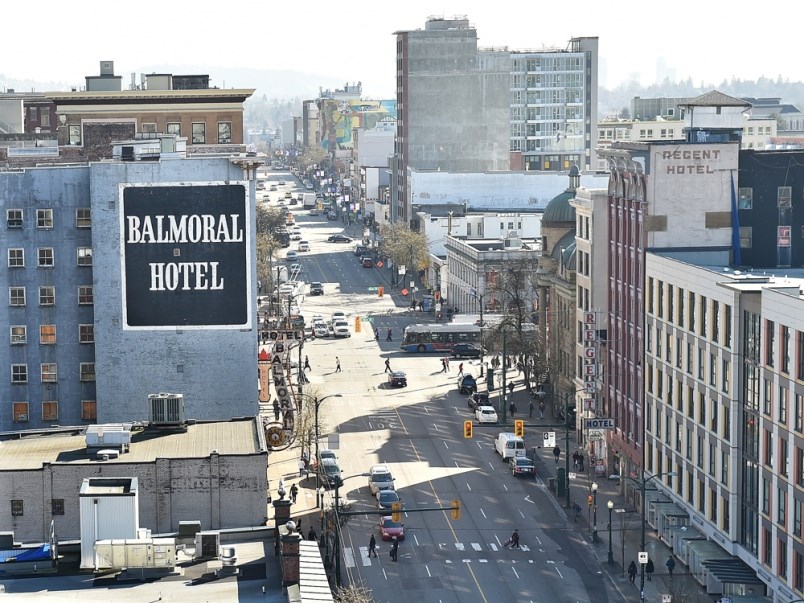

An additional 732 rooms across 10 buildings, including more than 300 rooms in the Balmoral and Regent hotels near Main and Hastings, were closed. The city is in a legal fight with the owners of the Balmoral and Regent to expropriate the buildings, which have been deemed unsafe to occupy.

Though unscrupulous landlords operating hotels in the Downtown has long been an issue in Vancouver — as previous city and police reports have shown — the report also points to the challenge honest owners have in keeping a hotel clean, safe and affordable.

“[Single-room-occupancy] hotels are difficult to properly maintain and manage at rents affordable to very low-income individuals without significant direct public investment in revitalization and operations, or indirectly through increasing the shelter rate component of social assistance,” the report said.

The report further states the high cost of upgrading 100-year-old buildings, combined with a rise in new investors who buy hotels in strategic locations on a speculative basis — or to maximize revenue from commercial or retail space — has intensified “two troubling building trajectories:” disinvestment and unmet health needs in the most affordable hotels, leading to deteriorating and unsafe conditions, and loss of affordability and displacement of low-income residents in the more well-maintained buildings.

“Generally, the worst [single-room-occupancy hotels] have lower rents, more frequent violations and house lower-income and often more marginalized tenants,” the report said.

“Where disinvestment is coupled with poor management practices, criminal activity, a lack of responsiveness by owners, and few to no tenant supports, the risk to both the buildings’ physical condition and the health and safety of its tenants is compounded.”

At the opposite end of the continuum, the report continued, new investor buildings have fewer violations, higher rents, and serve higher-income tenants, such as students or service workers.

In the middle are a number of hotels and rooming houses with owners who, to varying degrees, manage to maintain and operate their buildings without significantly compromising affordability, sometimes with a history or mandate of supporting low-income, new immigrant and working poor tenants.

“However, increasing financial pressures, limited supports for owners in addressing unmet tenant health needs, and a lack of adequate succession planning put these buildings at risk,” the report said.

“At each end of the continuum, both trajectories lead to the displacement of this very low-income cohort from private [single-room-occupancy hotels], leaving them with no real housing alternatives and contributing to increased homelessness.”

To address the concerns, the city met recently with the provincial and federal governments to discuss the formal creation of a joint investment fund to buy up to 105 privately owned hotels and renovate them for social housing.

Such a move would be expensive.

“Staff analysis suggests that the long-term vision of Housing Vancouver to replace all [single-room-occupancy hotels] with shelter-rate social housing could require government investment of approximately $1 billion,” the report said.

“Staff are working with senior governments to explore mid-term investment strategies to improve a significant portion of this vital stock.”

City council, meanwhile, approved a motion last year to slow the loss of single-room-occupancy hotels. Council directed city staff to pressure the provincial government to take regulatory action and explore the potential use of city tools to prevent rent hikes.

The report notes rent restrictions on private rental housing are challenging to implement and monitor, and can have “significant, unintended consequences” for tenants and operators.

“In light of this, past council policy and practice has prioritized advocating for senior government investment in new social housing and operating agreements, and for an increase to the shelter component of social assistance to a level that could enable private operators to adequately operate, maintain and renew [single-room-occupancy] buildings," the report said.

Note: This story has been updated since first posted.

@Howellings