|

ReVIEWS, preVIEWS, interVIEWS, and overVIEWS: here's where you'll find out what the Vancouver Book Club team thinks about the literary scene in Vancouver. What you should read, where you should go, who you should sit up and notice. |

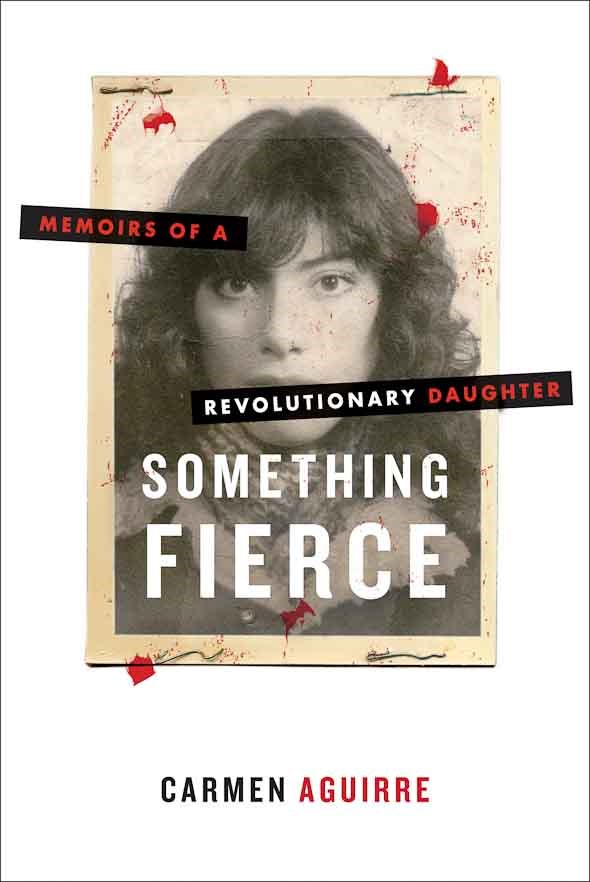

| A few weeks ago, thanks to "Canada Reads" CBC's annual battle of the books, everyone was talking about Carmen Aguirre's Something Fierce: Memoirs of a Revolutionary Daughter when it was chosen as the one book that everyone should read. Well, Lindsay Glauser has read it and she gives some more compelling reasons as to why you should read it. |

Vancouver playwright and actor Carmen Aguirre’s debut non-fiction book, Something Fierce: Memoirs of a Revolutionary Daughter (Douglas & McIntyre), came as a shock to the local theatre community because she kept her revolutionary experiences hush-hush over the last couple decades. But keeping secrets is a skill she has cultivated since she was very young. The book is aptly named: Carmen Aguirre is definitely something fierce.

During the '70s and '80s, Latin America experienced upheaval after upheaval as governments were built and toppled, while class after class of people were shuffled across borders or stopped and interrogated, or even imprisoned. Alongside these drastic shifts in the political environment, Aguirre recalls the tumultuous upheavals in her childhood. From her immediate family’s exile from their native Chile to her parents' eventual divorce, then through the family’s move back to South America for her mother and step-father’s resistance work, Something Fierce tells of the many ups and downs caused by her parents' decisions to take Carmen and her sister along for the ride. The author describes a life that was always part of her mother’s resistance: “As far as she was concerned, a woman shouldn’t have to choose between motherhood and revolution. She wanted both.”

As a child Carmen believed in the morality of her family’s involvement, and they dedicated everything to fight Pinochet’s oppressive government with both their bodies and their minds. Having such ideals and learning when to keep quiet when witness to atrocities such as racism, poverty, and alienation, prepared her for this life:

“I watched as the big-city guy kicked and spat on the old mule who stood in perfect stillness, his dignity intact. I was sorry that Peru wouldn’t be our last stop. I wanted us to join the resistance here so we could help the angry teenagers in the streets and the little boy outside the hotel and the chambermaid whose children were dying of diarrhea and the Indian family who had carried the tables and chairs for the Austrians and this old mule take the streets and squares and mountains and make Peru their own. I’d be ready to participate in whatever way they wanted me to.”

After their first stay in Vancouver, her mother and step-father moved to Bolivia to be in closer proximity to the dealings of the underground resistance, and where they could to actively take part. Here, Carmen experienced the rites of passage familiar to many young girls, but with a twist: meeting new friends (and young men) in the environment of family secrecy, uncertainty, sacrifice, and politics. Beyond her school and extra-curricular activities, she encountered potentially dangerous situations as a revolutionary daughter all while keeping her parents' activities on the down-low. As a teenager in Vancouver again, her involvement as a youth resistance worker was to politicize her high school, where she was met with privileged ignorance. Saying she felt out of place would be an understatement, but she describes the solidarity work in Vancouver’s Chilean community as “the reason to live.”

Something Fierce reflects upon these many hundreds of displaced people; perhaps the cruelest of all forms of torture is the torture of alienation. But beyond the politics of Latin America, she aptly describes the longing for a culture, a home, a people, while living outside her country’s borders. I can’t help but wonder what the draw is to a particular point of geography; she spent most of her life in exile from a place she so passionately defends. But again that is the point:

“The last time Ale and my mother and I had been on a plane we’d flown north, in the middle of the night, as people wept into their hankies. Someone had spread a Chilean flag and a banner of Allende in the aisle. When the pilot announced over the loudspeaker, 'We have crossed the border into Peru. We are out of Chile,' the passengers, grown men and women, had cried even louder. Someone started singing the Chilean national anthem, and everyone joined in. My parents put their arms around us and said, 'You will never forget this. You. Will. Never. Forget.' "

When they lived in Vancouver, they met and formed a community of exiled Chileans, some who fled after their bodies were ravaged by torture, and the psychological fractures exiles must experience. They were driven by the fact that they couldn’t go back, and by the loss of personal items, which is the equivalent of losing your identity.

“We were the only exiles among our friends lucky enough to have personal pictures from Chile. My grandparents had brought them when they came to visit us in Vancouver. They’d brought Chile with them in their pockets, their suitcases, their eyes and voices. I’d smelled a country on them when we greeted them at the airport, a country that still clung to my own skin and hair. It was something fierce, that country.”

Many had no proof of where they came from, only the memories, and the pain of exile. By breaking up the people, the Pinochet government was breaking up the collective identity of a people. Aguirre doesn’t romanticize resistance work. She describes the terror of living in secrecy, and hearing stories that would make you sweat from total paranoia. She also alludes to the conflict between her siblings, and the childhood they didn’t get to experience in that political environment, but ultimately Aguirre has come to a place of compassion for her mother’s sacrifice, and an appreciation of the gifts this unusual experience has given her.

Aguirre’s Something Fierce is proof that when you give your life to a cause, it’s not just your own cause -- you can’t turn a blind eye. Her travels within the resistance movement show the network of global citizens, including Swedish, Canadian, and British people, as being passionately involved in the Latin American struggle. Vancouver became the place of refuge for her displaced family and co-patriots after they were blacklisted by the Chilean government, and represents the very reasons why we feel the same pride in our country: that we are able to live side by side with people who unwaveringly and passionately defend the rights of others -- whatever the geography, the culture, the language -- and despite our own freedom. This isn't the story of a family that talked politics around the dinner table. This is the story of a family who stood up and did something.